Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

1985 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet June 1985 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1985.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

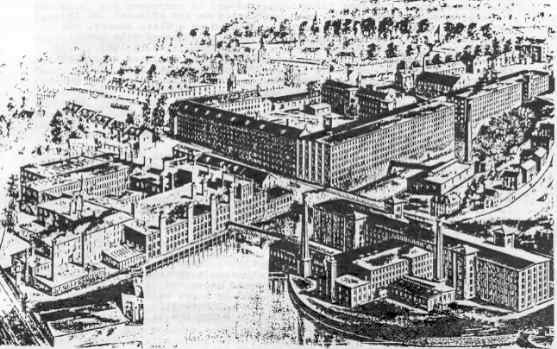

Cocheco Manufacturing Company Ca. 1879

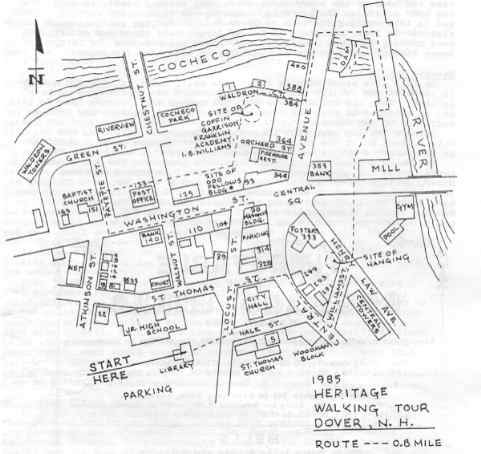

The neighborhood surrounding Central (Lower) Square serves as the focus for Dover’s 7th Annual Heritage Walk. Although the area, crisscrossed by Washington and Central Streets, had been residentially occupied since the 1640s, it was not until the great cotton mills, established by the Dover (later Cocheco) Manufacturing Company, were erected that the area saw phenomenal growth and development.

The mill owner’s needs for workers, services, and material suppliers made Central Square bustle. From the 1820s through the 1840s, this neighborhood was Dover’s boomtown, housing and employing over one third of the town’s population.

Lower Locust Street

During the 1850s, Locust Street was extended from Hale Street north to Washington and the street became a major thoroughfare. The Dover Public Library was built here on land donated by William Hale and with funds given by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. In 1904, Mr. Carnegie donated $30,000 for the Library’s construction provided the city of Dover would continue to support it with $3000 per annum. The building opened in July, 1905, and is currently undergoing a $ ½ million renovation.

Dover’s second high school was constructed on the adjacent lot in 1902. The Ida B. Hanson annex, originally used as a State Armory, was added in 1927 and the building was converted to a junior high school in 1967. A $2 ½ million renovation project was completed in 1981.

Across the street sits Dover’s fourth municipal building (the first three having been destroyed by fires). The present City Hall, which houses the Dover Police Department on its Locust Street side, was built in 1935 on the site of the former City Hall and Opera House which burned in 1933. Dover’s first two city halls were at the site of the present Masonic Temple. The current building, designed to be fireproof, is of Georgian Colonial design, houses an auditorium able to hold 900 people, and contains, in its 80 foot tower, the bell from the original Opera House.

In its earliest days, the lower end of Locust Street was dominated by three types of businesses: harness makers, grocers, and undertakers. Anderton’s Block (now Granite State Tobacco) contained Cartland’s Grocery for many years, and in the building housing the Ole Farm Pub was a harness maker and Smalley’s Monuments. The present parking lot (at that time the back of the Belknap church) housed Glidden’s Undertakers. Lower Locust Street never contained the “fashionable” shops; it merely provided its customers with the necessities of life (and death).

Seavey’s Hardware Site (now N.H. State Liquor Store)

Originally the site of Thomas King Atkinson’s residence, and founded in 1879 by J. Herbert Seavey, this hardware store was at 300 Central Avenue for 100 years before moving in 1980 to a new building at the corner of Chestnut and Washington Streets. J. Herbert’s son, Norman, bought the original building from landlord Henry Law in 1930 and the store remained in the family until 1944.

Belknap Congregational Church (now parking lot)

An offspring of the First Parish Church, the Belknap Congregational Church was organized June 30, 1856. For two years, services were held at City Hall, but by 1859 the brick 45 x 50 foot church was built for $16,000. The first floor of the 320 Central Avenue edifice always housed stores so that the church could receive rental income and religious services were held upstairs. The Church closed in 1881 and was severely damaged in the 1889 City Hall fire next door. It was subsequently repaired and services were again held until a second closing in 1896. Another fire, this time at the Masonic Temple in 1906, again damaged the church. Once more it was repaired and reopened in 1909.

In 1911, the Belknap Church was closed permanently although members of the Belknap Society continued meeting until November, 1963. At that time, the remaining three members of the Society voted to disband. The church was razed ca. 1965 for the current parking lot.

Foster’s Daily Democrat

Begun in 1872 as a weekly newspaper by Joshua Foster, Foster’s Weekly Democrat quickly gained popularity and daily editions commenced in 1873. In its early days, the newspaper office was housed at five different locations in the Central and Franklin Square areas before finally moving to its present spot at 333 Central Avenue in 1895. Major expansions and renovations have occurred regularly at the site, and ownership of the newspaper still remains in the Foster family.

Central Avenue (from the Square south to William Street)

One of the first brick buildings built by the owners of the mills was the Cochecho Block, located on the east side of what is now Henry Law Avenue. Constructed in 1832, the block housed retail businesses and offices and later on, the post office and Dover’s first public library. It was erected in five sections, each section with three stories and granite fronts. The interiors of the Cocheco Block were demolished in 1913 but the granite fronts were left standing for a few years after that.

Many of the other brick blocks around Central Square date from the 1840s, but this section of Central Avenue south of the Square and including Williams and Payne Streets was at first highly residential. Unmarried mill girls lived in boarding houses here and whole families occupied multi-unit dwellings in this locale that were built and run by management of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company.

In 1825, mill owners built “six blocks of two houses each, all occupied by at least two families,” in this area and “removed, repaired, and enlarged six others.” The Cocheco Manufacturing Company hired widows to run the boarding houses and paid $1.25 a week to board the girls in addition to their wages. Girls could get permission to live elsewhere but this practice was discouraged. A newspaper ad from the period asks for “50 smart capable girls, 12-25 years of age, to whom constant employ and good encouragement will be given.” Apparently the system worked quite well as the mill owners boasted in 1835 that “there has never been a case of bastardy at Dover.” John Williams, for whom Williams Street was named, was the Cocheco Manufacturing Company’s first agent and a benevolent boss who cared for his workers, even setting up a “Sick Fund” for the girls. The mills also hired whole families and advertised “jobs for all and a house for $90 a year with a basement, $75 without.” These duplex units were located in the Payne Street (now Henry Law Avenue) area.

Williams Street (Swazey’s Hill)

At the foot of Williams Street (originally known as Swazey’s Hill), in what is now Henry Law Park, the scaffold stood for Dover’s first hanging, June 3, 1788. Spectators came from all over Strafford County to sit on the side of the hill and witness the execution of Elisha Thomas for the murder of Captain Peter Drown. Thomas and Capt. Drown, both Revolutionary War veterans, were in a pub in New Durham when Thomas and another man became involved in a drunken brawl. When the Captain tried to break up the fight, he was accidentally stabbed and killed by Elisha Thomas. Dover, being the county seat, was the site of the hanging and it is said that the sheriff treated Thomas with tenderness and humanity, “shook his hand and he was launched into eternity.” Thomas was buried at Pine Hill Cemetery in a grave marked simply “E.T.”. The stone was erected in a north-south direction instead of the customary east-west facing because he was convicted murderer. The Daughters of the American Revolution later erected a new east-west gravestone with Thomas’ full name and exemplary war record.

Payne Street/Henry Law Avenue

Originally laid out in 1825 by the Cocheco Manufacturing Company for its mill housing and named for one of the company’s major investors, William Payne, Payne Street was renamed ca. 1933 for Mr. Henry Law, a locally renowned benefactor.

Henry Law was born in England in 1842 and came to Dover at age 21. He owned a harness shop at Central Square, but made his real fortune buying real estate in the area. Mr. Law himself lived a frugal bachelor’s existence in a home on Walnut Street near Washington, but he was eventually able to own all the property from Washington Street to St. Thomas Street (except the Belknap Church and the Masonic Temple). He was an active member of the Park Department and always loved children. His donations to the city built the swimming pool at Bellamy Woods, the wading pool on Payne Street, and he gave the land for the site of the present Recreation Center. He died in 1938, at age 96.

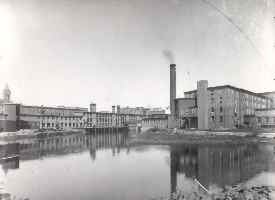

Cocheco Print Works

Calico printing started in Dover about 1826 in Mill #4 of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company. In 1827, agent John Williams brought five master printers from England to instruct the Dover printers in the intricacies of the block printing craft, all done by hand at that time. The Print Works employed highly skilled and talented workers and the industry expanded quickly in Dover. Separate facilities, approximately fifteen buildings filling what is now Henry Law Park, were constructed between 1842 and 1844, and cylinder printing (by machines that could do the work of 100 men) was introduced. By the 1880s, Cocheco Prints were renowned worldwide for their color, texture, diversity and quality.

At the Print Works’ peak, over 65 million yard of cottons, lawns, and organdies were printed at Dover each year and 400 men and 40 women were employed there. But after the company changed hands in 1909 and the northern textile industry suffered a decline, the machinery was removed to Lawrence, Massachusetts headquarters of the Pacific Mills. The buildings on Payne Street were torn down in 1913.

Cocheco Manufacturing Company

The first cloth manufacturing industry in town, the Dover Cotton Factory, was incorporated in 1812 and production began in 1814-15 at a wooden building called Mill #1 at the Upper Factory Falls of the Cochecho River, two miles above downtown. Founders John Williams and Isaac Wendell eventually were able to buy Daniel Waldron’s land at the downtown falls where a nail and anchor factory had been operating (the end of 180 years of Waldron ownership of this land).

Williams and Wendell built a four-story brick mill (called #2) at that site (now the fish ladder on Central Avenue Bridge) in 1822. In 1823, with increased capital, the name was change to Dover Manufacturing Company and production increased. Mill #3, five stories high, was built on Main Street in 1823, #4 (curving from Main Street around Washington) and #5 (on Washington Street), each six stories high, were completed by 1825. Mill #6, on Central Street, three stories and 185 feet long, was built in 1826. Power was supplied by overshot water wheels, some 28 feet in diameter “the largest in existence”.

In 1827, the name was changed once again to the Cocheco Manufacturing Company and investors from Boston were brought in to increase capital and stimulate more production and profit. The new owners, in 1828, replaced agent John Williams with a new harsh taskmaster, James Curtis, who was to enforce new rules. Regulations forbade any talking between employees during working hours, prohibited “combinations” (unions), imposed a 12 ½ c fine for lateness, and reduced the operatives’ wages from 58 ¢ to 53 ¢ per day.

Female workers soon rebelled and on December 30, 1828, Dover was the scene of the first women’s strike in the United States, About half of the 800 mill girls walked off the job and paraded around the complex with banners, signs, and fireworks. All was in vain however, as the Cocheco owners simple began advertising for 400 replacements. In fear of losing their jobs, the women returned to work, no better off, on January 1, 1829. A second strike by female workers, no more successful than the first, occurred for three days in 1834. As usual, the will of the company prevailed.

From 1876-78, a new Mill #1 was constructed at the site of the present day Clarostat, all water wheels were replaced with turbines, and overhauls of all the original mill structures were begun.

During the 1880s, a new #2 on the north side of the river was built and eventually #2, 3, & 4 were joined to form one continuous building 732 feet long by 74 feet wide. By 1885, the Cocheco Manufacturing Company had five mills and the printery in full operation. Over 1200 persons (2/3 women) were employed there, operating 128,000 spindles and 3000 looms.

But as the southern textile industry blossomed with lower production costs and cheaper labor, the northern textile business declined. In 1909, Pacific Mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts took over the company and tore down the Print Works in 1913. Operations slowed then stopped entirely in 1940. The physical plant was sold at auction to the city of Dover in 1941. A “Mill Committee” made up of city officials, then leased space in the facilities to smaller industries such as Miller Shoe and Eastern Air Devices. Currently, the mills have been purchased by private developers and are being refurbished and renovated to house retail and commercial businesses in the near future.

Central (Lower) Square

Central Square was originally a gully with a small brook running through it from Reservoir Pond (now the library parking lot) to the Cocheco River. Travelers would cross the square and ascend a hill up Central Street in front of what is now the Spartan Hotel: “a rise as high as the second stories of the buildings now lining the street.”

The square really began to develop when the mills were built (1822-1826), the Cochecho Block erected (1832) at the corner of Payne Street, and the Town Hall built (1842) at the site of the present Masonic Temple.

Most of the brick blocks bordering the square were built during the 1840s and these buildings: Marston’s, Varney’s, Freeman’s, and Tetherley’s, housed retailers, professional offices, early banks, newspapers offices, and served as headquarters for various fraternal organizations.

The hill just north of the square was cut down in 1844 for the construction of Varney’s Block, then Orchard and Walnut Streets were opened. It is said that several Indian skeletons were discovered at that time.

Central Square Looking south

Strafford Banks

In 1803, the N.H. Strafford Bank opened in a two-story wooden building on Central Street near Angle. The following year, the entire building was moved onto Angle Street where it still exists today. In 1821, the bank changed its name to the Strafford Bank and in 1847 moved with The Savings Bank for the Country of Strafford (inc. 1823 at Tuttle Square) to a three-story brick building on Washington Street. In 1895, the two banks (now known as the Strafford National Bank and the Strafford Savings Bank) moved into their new bank building adjacent to their former headquarters. The granite block on the corner of Washington and Central, built for $100,000 and designed by local architect A.T. Ramsdell, was called a “fortress of finance”.

In 1963, the Strafford Banks relocated once again to 353 Central Avenue; that building, now the home of the Strafford National Bank, was expanded in 1969 and 1973. In 1984, the Strafford Savings Bank, now called the Southeast Bank for Savings, moved to its own new brick structure on Washington Street across from the post office.

Central Avenue (from the square north to the bridge

While the east side of Central Avenue from Central Square north to Morrill’s Furniture has, for most of its history, housed mill-related functions, the west side of the street has always been commercial. Marston’s (later Union) Block was at the corner (now the old Stafford Banks building) from 1844 to 1895; Varney’s Block (364-374 Central Avenue) also constructed in 1844, still exists. The next two brick blocks, recently restored, were called Merchants’ Row when they were built in 1828-29 by the Cocheco Manufacturing Company. East and West India goods, barbers, milliners, tailors, and apothecaries sold their wares here.

Next to Merchants’ Row and adjacent to the bridge there was originally a wooden building built in 1822. Tredick’s store was here in 1830 and in 1834, Jacob Purington moved his hat store to this location. The business was taken over by John T.W. Ham, “Ham the Hatter”, in 1877 and the building rebuilt with brick in 1900. Mr. Ham did not retire until 1924.

The Urban Renewal Area

Between 1974 and 1978, the city of Dover undertook a $9 million urban renewal project that encompassed the Orchard, Waldron, Myrtle, Chestnut, Fayette, and Green Street areas. 15.8 acres including 119 dwelling units, 56 buildings, and 33 businesses were razed. Waldron and Myrtle Streets were eliminated and the entire face of the neighborhood, which had become dilapidated, changed dramatically.

Several buildings were saved by restoration-minded citizens: the Trela and O’Neil houses (early 1830-40 examples of mill housing), the old Central fire station, and the Public Market building; the Brennan house on Orchard Street and the Odd Fellows building on Washington Street were not.

The history of this area dates back to Dover’s earliest days when Major Waldron deeded this land all the way up Washington Street to the Tolend to Peter Coffin, a saw mill owner and prominent citizen, ca. 1650. Coffin’s garrison was atop the hill here at Orchard Street and was burned and pillaged along with several other Dover garrisons during the Indian Massacre of June 1689. However, unlike Major Waldron, Peter Coffin had treated the Indians fairly in the past, so his and his family’s lives were spared. This land, largely undeveloped and covered by woods and lush orchards, remained in the coffin family until Peter’s great-granddaughter Deborah’s death in 1838.

In 1818, the Franklin Academy, a college preparatory school, opened on land near Waldron Street. The first public building built of brick in Dover, the Academy had, for its first 25 years, an entrance on Central Street bordered by a large front lawn and the orchards in back. In 1844, when Orchard Street was cut through, the entrance changed to Washington Street and Myrtle Street opened directly onto academy grounds. The school closed in 1896 when the building was acquired by the I.B. Williams and Sons Belt Factory. John Scales, author of The History of Dover, served as the last headmaster.

Franklin Academy

Isaac B. Williams started his leather belting shop in rooms in the Cocheco Mills in 1842. In 1875, needing more space, he moved to an abandoned three-story shoe shop on Orchard Street. Additions and renovations were made every few years until the factory had 70,000 square feet of floor space and ran 100 feet on Orchard Street and 315 feet on Waldron Street.

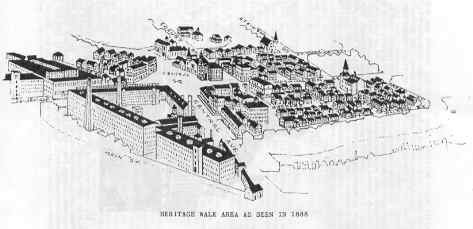

Heritage Walk Area as Seen in 1888

After Isaac’s death in 1885, his son Frank took over and the company’s business grew to over $2 million annually, both here and abroad. Frank Williams was succeeded by his son-in-law, Philip C. Brown, who ran the company until 1958. I.B. Williams and Sons continued in business until the early 1960’s, but after the sale of the factory buildings in 1945, they moved to the mill buildings on Washington Street and no longer manufactured products but only acted as brokers.

In 1945, the buildings and machinery on Orchard Street were sold to Isadore Osman and George Limon who renamed the firm United Tanners. The buildings were re-equipped with machinery for making side leather used in shoes and handbags rather than belting. The tannery closed in 1976 with 125 employees and the buildings were subsequently torn down.

Also on Orchard Street, now the Firehouse Restaurant restored in 1978, is Dover’s first central fire station, built in 1865 to house the city’s first steam engine fire truck. Prior to a central station, neighborhood fire societies had existed in Dover as far back as 1795 but these small stations were inadequate for a growing city. The Central Station was constructed in a flat-roofed Romanesque style with a large hayloft inside (for the horses that pulled the engines) and a wooden floor. It served 34 years before a more modern facility was built on Broadway in 1899. The Orchard Street station was still used, however, until at least 1934. The wooden floor was replaced with cement to carry the weight of the modern heavy fire trucks. The Dover Veterans Council occupied the building from 1965 through 197

Other businesses in the Urban renewal area included the Dover Business College (later McIntosh College) at 16 Orchard Street, the American Dye House, Varney’s Cleaners, and Newsky’s Grocer

Washington Street businesses (north side)

Washington Street was established in 1826, over the objections of the Coffin family, so that farmers from the Tolend, tired of being detoured all the way around Silver Street, could come into town by a more direct route. At first largely residential, with most occupants working in the mills, Washington Street began to be developed in 1843. During that year, the brick block now known as the Public Market building (93 Washington) was built and housed E. Morrill Furniture until 1920. The brick Strafford Banks building was constructed between 1845-47 and in between these blocks were Varney’s Rexall (89 Washington) and Tufts’ (85 Washington) drug stores

On the left side of the Public Market building is the site of the former Odd Fellows building. In 1843, the Free Will Baptist Printing Establishment, publishers of a weekly religious newspaper, “The Morning Star”, and one of Dover’s three Baptist churches jointly constructed a 2 ½ -story Greek revival-style building here. The printery was on the first floor and the church on the second. In 1868, the printery needed more room so the church sold their share and built a new church on the corner of Washington and Fayette Streets. The printing establishment modified the building, a mid-19th century fire caused further changes, and it was eventually rebuilt as a four-story building with a Mansard-style roof. The Free Will Baptists used the structure until 1869 when they began leasing it to the Odd Fel

The I.O.O.F. bought the building in 1885 and completed $3000 worth of renovations. Several rooms in the building served as home to the Dover Public Library from 1886-91. Whiting’s Stationery was the last business housed here. It was torn down in 1978 when no buyer could be found to develop and restore it.

Post Offices

The site of the Dover Post Office has been the “home of the mail” since 1909, its longest tenure in any one location in the city: in its first 114 years of existence in Dover, the post office moved eight times. The first postmaster, Ezra Green, operated out of a home on Silver Street in 1796. Then the post office moved to a Tuttle Square location, then to Tufts’ drug store at Central Square, to the Cochecho block, then to Marston’s Block, the Dover Bank building, the Walker Block, and to the corner of Washington and Walnut Street

Some of the houses on the site of the present building were moved to Belknap Street when construction began in 1909. The current structure was expanded and renovated in 1962-63 and the entrance changed from Washington Street to Green Street in 1979.

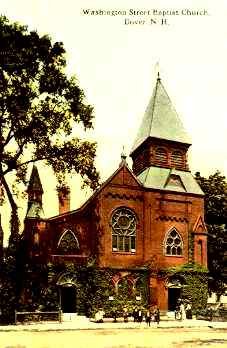

Dover Baptist Church

The establishment of the mills in Dover brought with it the organizing of many churches. There were only two churches here in 1800, but by 1840 there were ten. Three of these were Baptist, and one of these, the Washington Street Free Will Baptists, was organized in 1840 and met in the building on Washington Street previously mentioned as the Odd Fellows building.

In 1868, they built a new brick church here on the corner of Washington and Fayette Streets at a cost of $20,000. An 1882 fire gutted the structure and the present church was rebuilt in 1883. In 1918, the Washington Street Free Will Baptist Church joined with the Central Avenue Baptist Church to form one congregation called the Dover Baptist Church. The Washington Street building would be used for church services while the Central Avenue building (now the site of Dunkin Donuts) would become a recreation hall. The Central Avenue property was eventually sold and the money was used in 1951 to build the current Sunday School Building adjacent to the churc

In 1957, the church started buying houses behind the building to provide for a parking lot and this culminated in the present lot when the urban renewal project changed this area in 1977.

Then in 1981, the church was able to own this entire block when they purchased the house next door to the church building (the only house left on the block). The house has just been renovated for use by church missionary families home on furlough. It is believed that this house was originally built at the Upper Factory Village and moved to this site in 1842. Many houses from the Upper Factory (called Williamsville after agent John Williams), which at one time was home to 300 inhabitants, were moved into town when the railroad tracks were laid into Dover through this village at the Upper Falls. It is said that by the next decade (the 1850s) no trace could be found that the village of Williamsville ever existed there.

Washington Street businesses (south side)

Although its early history shows multi-family homes in the area, this part of Washington Street, by the 20th century, was defined by the advent of the automobile into Dover. Brodhead Ford, Wentworth Automobile Station, Rowe Chevrolet, Kenmore Motor Company, Dover Buick, and the Belknap Tire Company all had their starts here. Robbins Auto Supply (estab. 1933) still continues here.

The present Robbins Auto location was the site of the Orpheum Hotel which opened in 1914 with 40 rooms and five baths. The adjacent Orpheum Theater opened ca. 1912, later was known as the State Theater (1936), and finally closed about 1955. The Hotel has just recently been closed in conjunction with the renovation of the building.

Orpheum Theater

At the corner of Washington and Locust Streets is the Walker Block, built ca. 1880 with three stories. It was the first the site of Folsom’s (later Kennedy’s) paint and hardware store, then in 1906, after a fire burned them out of their Masonic Temple location, the block became the home of the Dover Cooperative Bank (estab. 1890). In 1953, the bank renovated the building, removing the third story entirely, and in 1955 changed its name to Dover Federal Savings and Loan Association. In 1961, buildings on Locust Street were razed for an adjacent parking lot, but eventually more space was required. In 1972, Dover Federal moved to its new building at 633 Central Avenue.

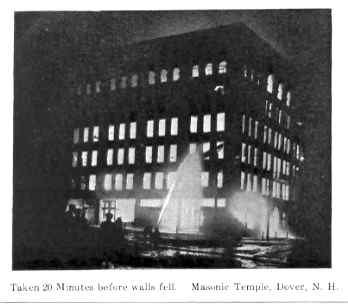

Masonic Temple

On this site stood Dover’s first town hall, built in 1842 and burned in 1866. It was rebuilt here shortly afterward and burned once again in 1889: “When the building was flat all seemed well pleased for it was an abortion in plan and construction…Its destruction was little regretted by our citizens.”

Perhaps feeling that this location was doomed to disaster, the city fathers built the third municipal structure, the Opera House, up the street a way in 1891 (unfortunately this also burned, in 1933).

The Masonic organizations, the Strafford Lodge and the Moses Paul Lodge, which has been housed at various locations around downtown Dover, decided to build their Temple here and it was completed in 1890. It seems the site was doomed after all as a third fire occurred here March 29, 1906, destroying the entire structure. The present Masonic Temple, a Romanesque revival design costing $75,000, was rebuilt in 1907 and rededicated in 1908.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.