Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

1986 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet June 1986 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1986.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

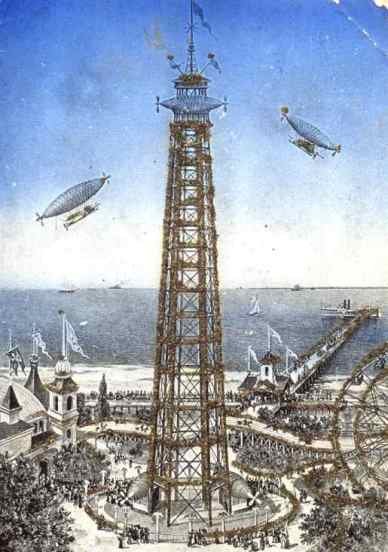

Garrison Hill & Wooden Observatory Ca.1885

Rising to a 298 foot elevation overlooking the city of Dover, Garrison Hill served for over one hundred years as a recreational site.

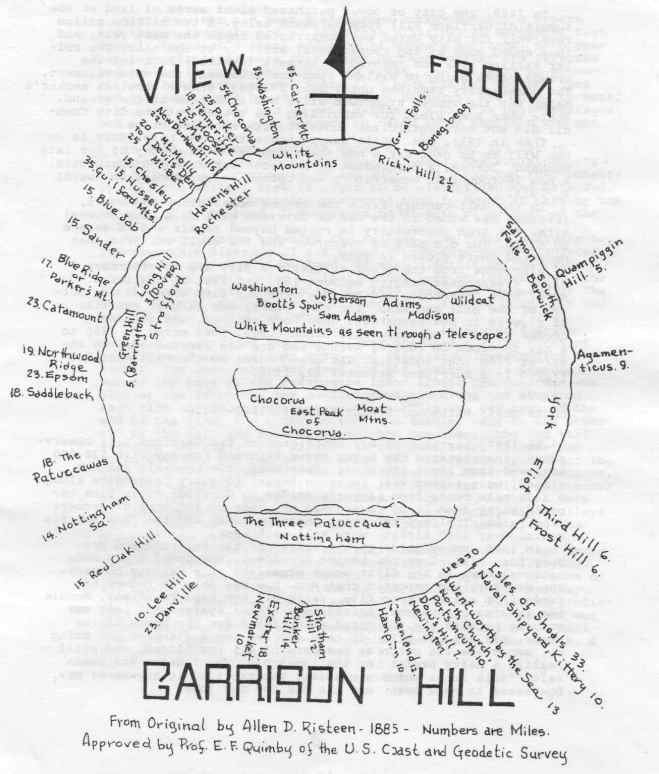

On a clear day, both the peaks of the White Mountains and the Isles of Shoals could be spotted from the observatory atop the hill.

A roller skating rink, a restaurant, and numerous band concerts flourished here during the park’s heyday in the 1880’s, and a street railroad carried passengers by horsecar to picnic in its beautiful groves.

Garrison Hill

First known as “Great Hill” in the 1650s, Garrison Hill was formed during the Ice Ages into a geological formation known as a drumlin. The Wentworth, Heard, Otis, Varney, Sawyer, and Ham families owned much of the land here originally and farmed the still-unforested crest of the hill.

In 1696, Ebenezer Varney, a blacksmith and devout Quaker, built his home at the foot of the west side of Great Hill. Varney was a great friend and benefactor of the local Indians, and his home and his family were never in any danger during the Indian turmoils that plagued Dover in the 1700s. The hill eventually became known as Varney’s Hill during the eighteenth century. In 1829, John Ham purchased Varney’s property and by 1834, the name had changed to Garrison Hill. The Varney-Ham house remained in the Ham family until about 1920 when it was sold to Phillip Daum. The house was taken down ca. 1970 when the large apartment complexes in that area were constructed.

Varney-Ham House

In the 1790s, Captain Richard Tripe had a boatyard on Varney’s Hill, and during the winter of 1795 hauled a 50-ton schooner down the hill through three feet of snow all the way to the landing at the Cocheco River.

By the 1850s, Garrison Hill was well known as a recreational site. When local Democrats wanted to celebrate the election of James Buchanan to the presidency, they brought a cannon, captured from the British in the war of 1812, and some fireworks and had a large parade and bonfire on the hill. Unfortunately, the cannon, nicknamed “The Constitution”, misfired and killed the two young men who were loading it. It was not used again until 1875 when it was fired for the July 4th Centennial Celebration atop of the hill.

By 1880, the top of the hill was jointly owned by Joseph Ham and a young entrepreneur who was cashier at the Cocheco National Bank, Harrison Haley. Haley built, for $1000, a wooden observatory 65 feet high, designed by architect B.D. Stewart, and modeled on a similar structure at Coney Island. Known as Haley’s and Ham’s Outlook”, the tower was five stories high with a mansard roof and open balconies on every floor. A 10-cent admission was charged to climb to the top where Haley had installed a telescope through which the public could see Mount Washington, 90 miles away. Over 6000 tickets were sold the first year. The observatory also had a small, 25 square foot restaurant in its base where light lunches and cold drinks could be purchased. The top of the hill was landscaped with hiking trails and a six-acre picnic grove and a roller skating rink with removable sides. Young Dover men came in droves to play in the roller-hockey league games at the rink. Haley also had plans to install a 102-foot high toboggan run that would extend 2000-3000 feet down the hill, but this project never materialized.

Coney Island Tower

In 1885, Dartmouth professor E.F. Quimby completed a topographical survey of the views from the top of Garrison Hill and computed the distance to various familiar landmarks in each direction. Quimby determined that 41 cities and towns and Maine and New Hampshire could be sighted from the observatory. The professor’s map is recreated on the next page:

In 1888, the City of Dover purchased eight acres of land at the summit of Garrison Hill from Harrison Haley. A two million gallon reservoir for city water was constructed there the next year, and thus ended much of the recreational activity at the hill. The roller skating rink was removed to Burgett (Central) Park and the crowds began going to Willand Pond for amusement and entertainment. The observatory remained until June 27, 1897 when a careless smoker’s match set the wooden structure afire and it burned to the ground. There were some pleas for rebuilding the tower, but the city council did not have sufficient funds for its reconstruction.

Then in 1911, Mrs. Abbie Sawyer bequeathed the city $3000 in her will to be used for a new tower dedicated in memory of her late husband; Joseph, a descendant of Ebenezer Varney and Richard Otis. A new 76-foot iron observatory was opened at ceremonies on August 2, 1913.

In the half-century since the second observatory was built, interest has waned in the use of Garrison Hill as a recreational site. The iron observatory is rusted beyond repair and is unsafe to climb. The old park is overgrown and the small ski area that operated there closed in 1979.

Also gone from the scene at Garrison Hill are the fourteen glass greenhouses erected between 1893 and 1901 by Charles H. Howe. Howe Greenhouse and nursery occupied five acres at the bottom of the hill and was, for many years, the largest retailer of flowers in New Hampshire. When Howe retired, the company became known as Garrison Hill Greenhouses. They moved in 1950 to a new showroom on Central Avenue and are now located just up the street from the location. The greenhouses on the hill were destroyed in a hurricane November 27, 1950.

Dover Horse Railroad/Street Railway 1882-1926

In 1882, Harrison Haley, proprietor of the Garrison Hill observatory, incorporated the Dover Horse Railroad Company with $20,000 borrowed from local investors. Four cars, two open-air and two closed, were teamed with fourteen horses to carry passengers along a 2.39 mile route from Sawyer’s Bridge to Garrison Hill. Each car could carry from 26-30 passengers who rode on 110 tons of wrought iron rails. Trolleys ran every thirty minutes and the fare was six cents. Over 5000 tickets were sold each week.

In 1888, Haley sold cut his shares of the railroad and Mrs. Mary Edna Hill Gray Dove became president. She immediately made national news as the first woman president of a railway company. The New York sun reported that Mrs. Dow was able to reduce the fares from six cents to five, raise all her employees’ pay, double her insurance coverage, introduce a ticket system that cost her nothing because she solicited advertising for the backs of the stubs, pay all her bills in cash and receive a discount for doing so, supervise the purchase and care of all the horses, and still realize a hefty profit or the investors. The Yonkers Statesman said: “talk about women’s mission! She can find it anywhere! Mrs. Dow seems to have been just the man for the job!”

Mrs. Dow, who had been a newspaper correspondent, a French and German teacher, and an assistant principal at Rochester High School, was also a vocal advocate of women’s suffrage. Each year her property taxes were paid under protest because she felt she had no say in where her money was spent. She was also an accomplished homemaker winning State Fair blur ribbons for her jams and jellies, brown bread, and tatting patterns. She loved to hunt, fish, and swim, and was an avid gardener with “the best asparagus bed in Dover”. She also managed to raise three children and get married twice!

In 1889, Mrs. Dow sold the Horse Railroad for $25,000 to Henry W. Burgett of Brookline, Massachusetts. She explained, “I had no lawsuits or trouble of any sort; and I ran the road honestly. All the while I knew it ought to be electrified and extended. Finally, a good opportunity presented itself. Moved in part by the illness of my husband, I consented to dispose of my part of the outfit.”

Mr. Burgett soon extended the railway from Franklin Square to Somersworth, a distance of six miles to his soon-to-be-completed amusement park at Willand pond. He also electrified the track with 60-foot steel rails so that horses were no longer used. The first electric car ran august 16, 1890 under the new name of the Union Street Railway. Burgett also built a power plant for the railway cars at his new park.

In 1892, the track from Franklin Square to Sawyer’s Bridge was also electrified and the railway operated a large fleet of seven closed cars, eleven open, and three snowplows. During the summer, the open cars were used and the benches were arranged across the cars so the passengers faced front. The motorman was also at the front and the conductor walked along the steps on each side of the car collecting fares. When the car reached the end of the line, the motorman took his handle, went to the other end of car, and mounted it in the box there. The rod that attached the top of the car to the overhead electric wire was taken down and the rod at the other end was raised to contact the wire to propel the car in the other direction. During the winter, the cars were closed and the seats ran along the walls of the car with an aisle for the conductor down the center. As there were no other vehicles on the road in the winter months, the trolleys plowed their own tracks, leaving huge piles of snow along the sides of the streets.

The Union Street Railway was badly managed, however, and foreclosed in 1896. Stockholders and creditors lost over $200,000. The company went into receivership and was bought out by some of its bondholders. It reorganized as the Union Electric Railway.

This new management group was able to run the railroad profitably from 1897 through 1901. At that time, they were brought out by Mr. Wallace Lovell and consolidated with the Rochester Railway. The company then became known as the Dover, Somersworth, & Rochester Street Railway.

The D S & R Railway ran hourly in the fall, winter, and spring, half-hourly in the summer, and every fifteen minutes in July and August after 1pm. Eventually, due to a combination of too-high fares (30c to Somersworth; 50c to Rochester) and too-cheap automobiles, the D S & R (in its later days known as the Damn Slow & Rough) ran its last electric trolley on September 15, 1926. Bus service was shortly substituted between the three cities and the rails were dismantled in 1927.

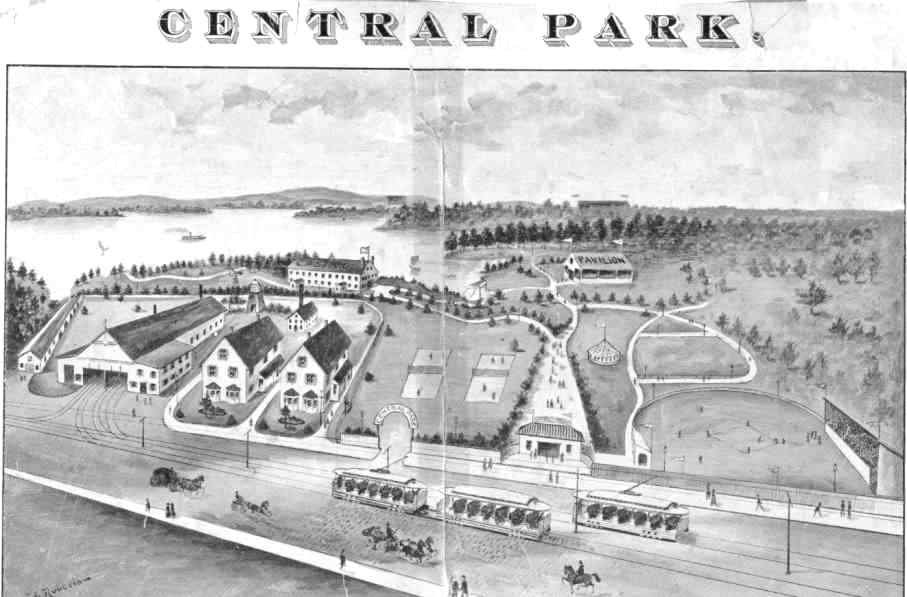

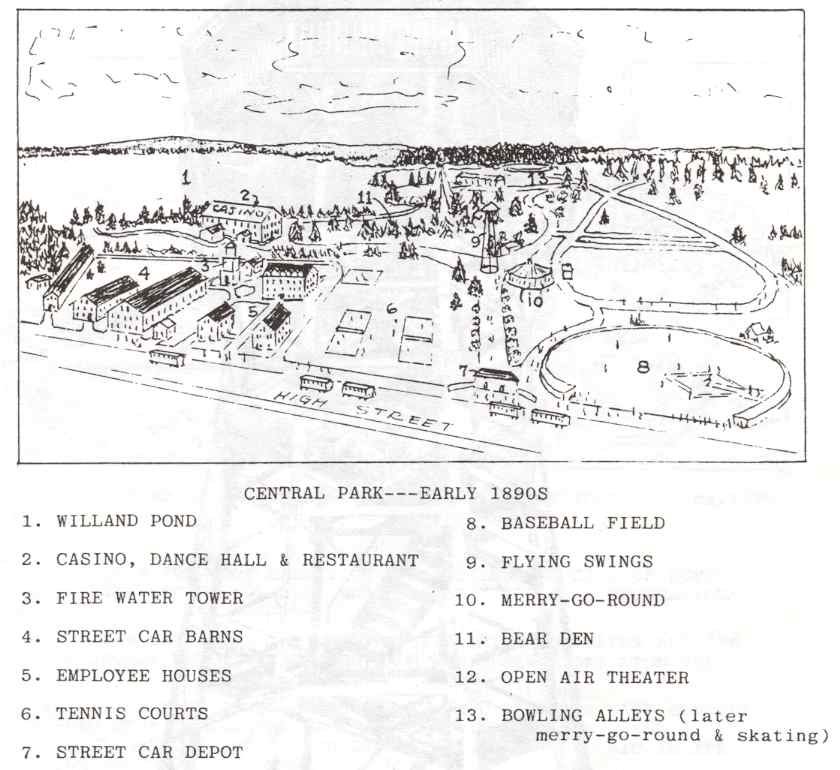

Burgett/Central Park

In 1889, Henry Burgett purchased, along with the Dover Horse Railroad, twenty- seven acres of land at Willand Pond. This body of water, 62 acres dividing the cities of Dover and Somersworth, had been the site of the State Fair in 1858 and was a natural place for an outdoor recreation area.

Burgett built a two-story casino (50’ x 100’), a pavilion of the same size for dances, a carriage house, and a power plant for the electric railway cars. Burgett Park opened on September 18, 1890 and was immediate success. Within a year, the park was renamed Central Park.

Its facilities were unsurpassed in the seacoast area and new features were constantly being added. During the early 1900s at the peak of its popularity, Central Park’s offerings included a dance hall with a highly-waxed 75,000 square foot hardware dance floor. The hall’s twenty windows opened on three sides to a wide veranda with views of the pond. Its interior was decorated with floor-length plate glass mirrors. A 1600-seat open amphitheatre was also on the site and offered lots of nightly entertainment ranging from Vaudeville shows and summer stock to boxing matches. There was also a bandstand for concerts, a penny arcade, and merry-go-round, roller skating rink, bowling alley, a bear cage with two live bears, a horseshoe pit, swings, several picnic areas, a lawn tennis court, baseball and football fields, a track for bicycle races, and rowboats, sailboats, and canoes to rent and steamboat rides around the pond for ten cents. On a typical Saturday night or Sunday afternoon, there were anywhere from ten to twenty trolley cars at Central Park.

Use of Central Park declined rapidly after the demise of the Dover, Somersworth, & Rochester Street Railway in 1926. The dance hall pavilion was used for special functions such as high school proms until about 1940, but eventually all the recreational building were torn down. One car barn still remains visible on High Street in Somersworth across from Tri-City Plaza.

Willand Pond, 65 feet deep, still remains unchanged, however. Dover has owned the water rights to its 514 million spring-fed gallons since 1899. An act of the New Hampshire Legislature passed in 1891 has prevented any pollution of the pond so its water is still quite pure. In 1959, a feasibility study was conducted at the site to determine if a State Park should be located here. The idea was eventually dropped due to the prohibitive $400,000 cost of developing the site.

Modern View of Garrison Hill Tower- built 1913

(when this booklet was published the tower was unsafe for climbing and not open to the public.

A new tower was built in 1993, and the public is free to climb it once again.)

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.