Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

1989 Heritage Walking Tour

This Heritage Walking Tour explores the events of a terrible day in Dover history from the colonist's perspective. Other sources consider what happened from the indigenous people's viewpoint. At the end of the booklet are more resources on the native Wabenaki tribe.

The Wabanakis targeted Major Richard Waldron in 1689 not only because of his notoriously duplicitous trading practices, but also because he had twice betrayed them during what everyone in the region called ‘the First Indian War”- that is, the conflict today most commonly referred to as King Philip’s War (1675-1678). Indeed, more than a decade after the 1689 Cocheco Raid, the Wabanakis still kept alive the memory of Waldron’s perfidy in the mid-1670s. The Reverend John Williams, captured in 1704 at Deerfield, Massachusetts, recorded that some Jesuits he encountered in New France “justified the Indians in what they did against us, rehearsing some things done by Major Walden above thirty years ago, and how justly God retaliated them in the last war.”

In the Devil’s Snare by Mary Beth Norton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, c. 2002.

Dover Heritage Walking Tour Booklet

The Cochecho Massacre: 300th Anniversary, June 1689 - June 1989 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1989.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

For over a half-century following Dover’s founding in 1623, the pioneering English men and women who settled along the banks of the Piscataqua and Cochecho Rivers were able to co-exist quite peacefully with the Penacook tribes who occupied the local territory. The Indians aided the colonists in the development of hunting, fishing, and farming skills necessary for survival in New England, and the white men introduced new and often delightful imported goods to the trading outposts. Although the Indians were not always treated fairly in their contacts with the English, the two races lived together amicably, one colonist describing the natives as “honest, honorable, and hospitable.”

The Indians’ chieftain, or sagamore, was Passaconaway, a strong, forceful leader who commanded wide respect and who demanded peaceful behavior from his people. His 50-year reign in the New Hampshire province was marked by its harmonious existence with ever-advancing English settlements.

Passaconaway was responsible for the formation of the Penacook Confederacy, (a unification of local tribes against hostile Mohawks), and his name appears on several peace treaties signed with the colonists during the 17th century. Passaconaway “retired” as chief about 1665 and in his farewell speech cautioned his people to remain on friendly terms with the English.

The mantle of Indian leadership then passed to Wonalancet, Passaconaway’s son who had been born in 1619. Wonalancet carried on his father’s peaceful traditions, even learning to read and converting to Christianity.

The leader of the colonists at Cochecho was Richard Walderne (Waldron), an Englishman who had emigrated to Dover ca. 1635. In 1640, Walderne had purchased a large tract of land at the Lower Falls of the Cochecho River, and in 1642 had built a sawmill there. That spot (now the middle of downtown Dover) was the origin of the settlement called Cochecho: up until that time everyone lived at Dover Point. This new inland settlement grew slowly as Walderne added workers to his saw, grist, and corn mills---a total of 29 families in 1662, 37 in 1663, and 41 in 1666. Walderne acted as town treasurer, selectman, representative to the General Court in Boston, and as local magistrate---roles certainly befitting the largest employer and the biggest taxpayer in the village.

Town residents were quite accustomed to the sight of Indians in Cochecho: the settlement served as a large trading post (also run by Walderne) for the area as far west as Concord. Walderne was not without occasional Indian problems however. Local laws prohibited the sale of firearms or alcohol to the Indians, but it appears Walderne sometimes disregarded those bans. In the 1660s, he was acquitted of selling liquor to the Indians, although tradition has it he lied under oath. Walderne who also accused, though it was never proven, of pressing his fist down on the weighing scales when conducting trades with the local tribes, thus charging the Indians more for the goods they bought with their pelts.

Yet overall, the racial climate in southeastern New Hampshire was favorable, each side compromising a little in order to live in peace with the other. But across the border in Massachusetts, a bloody war broke out during the summer of 1675. A Wampanoag chief named “King Philip,” bitterly stung by the wrongs he felt were inflicted on his people by the English, aroused the tribes of the Commonwealth to battle to drive the white men out of the colony. Philip tried to enlist Wonalancet’s help, but the peace-loving New Hampshire sagamore went into hiding: Wonalancet was too much of a patriot to fight against his native countrymen, yet too much a man of principle to break his treaties with the English. At Cochecho a local militia company was hastily assembled, just in case hostilities broke out locally. Richard Walderne was put in charge and given the rank of major.

One year later, the Indians who had joined King Philip’s legions had lost 3000 men, women, and children in the war, in addition to hundreds more who were sold into slavery. The New Hampshire tribes unfortunately bore some of the blame for Philip’s actions: even though the Penacook had tried to remain neutral or had sided with the colonists, many were tortured and killed by suspicious Englishmen who believed the local Indians were spies or accomplices for Philip. Yet Wonalancet and Major Walderne signed a new peace treaty in 1676 affirming their commitment to non-violence.

During that summer of 1676, many Massachusetts Indians fled to New Hampshire, hoping to escape death or capture. By September, over 400 Indians were at the settlement of Cochecho, about half of them strangers, the other half Wonalancet’s people.

On September 6, two companies of Massachusetts soldiers, led by Captains William Hathorne and Joseph Syll, arrived at Cocheco with orders to recapture the escapees. They were ready to battle the Indians, but Major Walderne intervened.

Walderne agreed that the Massachusetts Indians should be returned to Boston for punishment, but he did not want the local, loyal Indians to be harmed in the process. The Major suggested a “sham battle,” a ruse that could accomplish the captains’ orders, but without the bloodshed. The Indians were invited to assemble at a field close to town (the present-day Welby/Handy Hardware parking lot) for a day of war games: a mock battle.

Tradition claims that the English, knowing the natives’ love for gunpowder displays and their curiousity about fire arms, offered the Indians a cannon which they could fire during the “battle.” The sham fight worked perfectly: the militia companies of Walderne, Hathorne, Syll, and a fourth Company from Kittery easily surrounded the unsuspecting Indians who were preparing for the fight. Some accounts of this day say that some Indians were killed when the cannon misfired, but most reports regale the battle’s success because there was no loss of life. In any event, the local Indians were separated out and freed, but the 200 King Philip supporters were taken back to Boston. Eventually some of these were hanged for treason or sold into slavery.

Major Walderne had turned what could have been catastrophe into a simple military exercise. He felt he had done his patriotic duty to Massachusetts, yet had managed to save Wonalancet’s people from harm. But the Indians did not see it that way. Walderne became a traitor in their eyes and they vowed to wait patiently for an opportune time for revenge.

King Philip’s War ended two years later, in 1678, but sporadic Indian troubles continued to plague northern New England. Chief Kancamagus (Passaconaway’s grandson also known as John Hawkins) succeeded his uncle Wonalancet as sagamore to the New Hampshire Indians and his radical rule was noted for his dedication to warfare. Kancamagus had grown up observing the increasing instances of cruelty and injustice to his people as the English population expanded throughout the territory. He had been influenced by many of the militant participants of King Philip’s war and he knew firsthand of Major Walderne’s “betrayal” of the Penacooks at Cochecho.

Tensions mounted for the next eleven years. Indians were ordered and “enjoined on the sight of and English person…to immediately lay down their gunns” and no Indian had liberty to travel in the woods east of the Merrimack River without a certificate from Major Walderne. As the white men took more and more land from the Penacooks, the payment to the tribes for such encroachment was determined at “one peck of corn annually for each family,” hardly a fair payment.

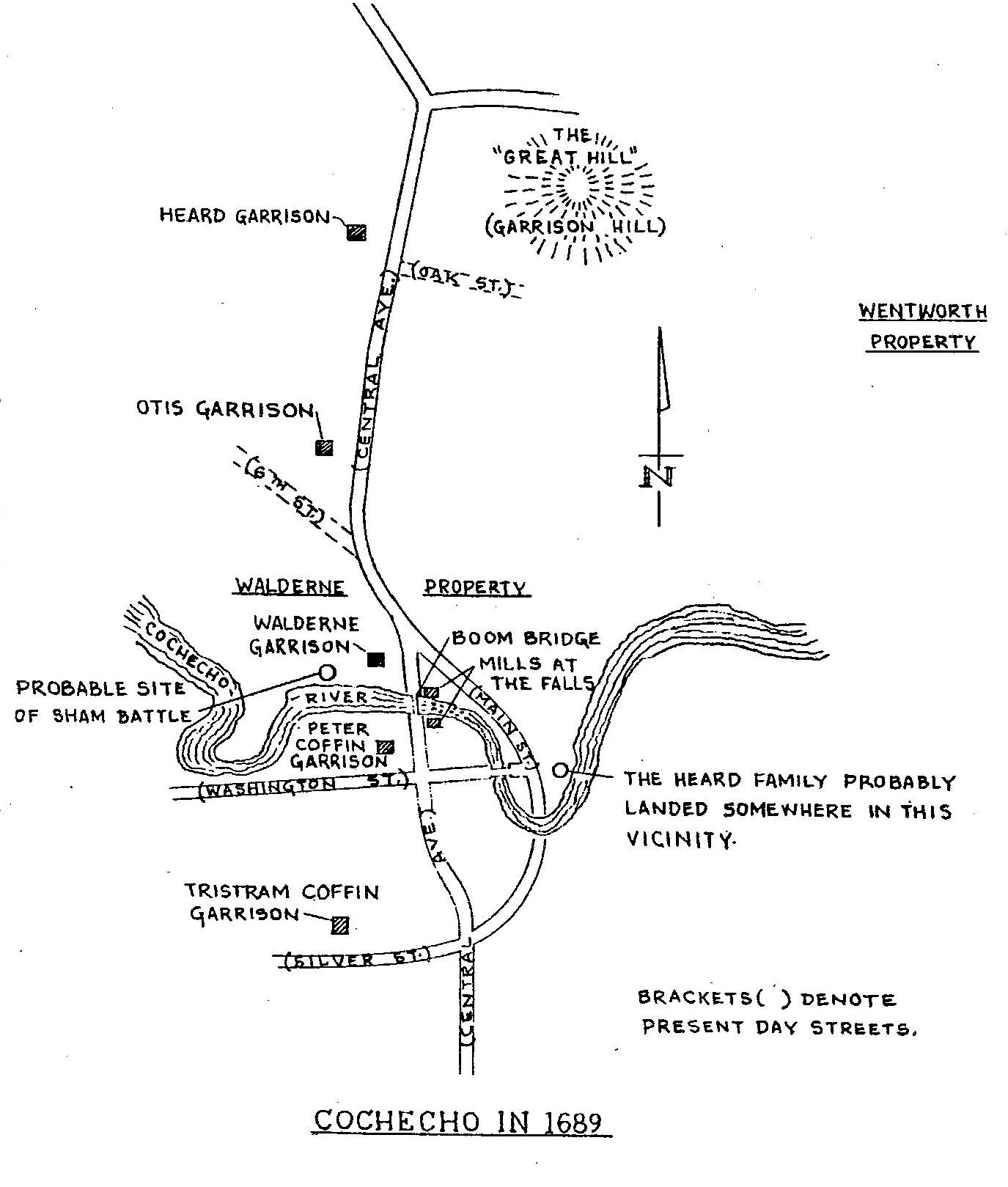

In 1684, the Governor and council ordered “that the meeting house at Dover be immediately fortified and a line drawn about it…for defending…against attacks of the enemy; …likewise, that the houses of Peter Coffin Esq. and Richard Otis be by-garrisons for Cochecho, for securing the inhabitants that dwell thereabout.” Clearly, not every dwelling was “garrisoned” at this time, but every neighborhood did develop at least one fortified blockhouse where people might flee to safety if Indians attacked. It is estimated that there were 50 garrisons within a 15-mile radius of present downtown Dover, most built after 1665. Five homes at the settlement of Cochecho were soon “garrisoned” at public expense following the governor’s orders: Richard Walderne’s, Richard Otis’, and Elizabeth Heard’s on the north side of the river, and south of the Cochecho the homes of Peter Coffin and his son Tristam.

These sites were purposely chose because of their locations on the highest knolls of the town: they would afford a good view of any approaching assault. Built with foot-thick squared logs impenetrable to bullets, the garrisons had center chimneys, dovetailed and pinned interlocking construction at the four corners, and a second story which projected over the lower story by two or three feet. This overhang feature was designed to combat Indians who customarily attacked with fire and smoke. A loose board in the overhang portion of the second story could be removed and water could be poured down on the fires below. Tradition has it that the women were stationed up there with kettles of boiling water ready to dowse the heads of the marauders.

Each of the four walls of the garrisons had horizontal slits or pyramid-shaped openings (the bases opening into the house and ending outside in a square hole a little larger than the Diameter of a gun barrel) that allowed the defenders’ firearms to be turned in any direction necessary to sweep the field in front.

As an additional protection, each garrison was then surrounded with an eight-foot high timber fence called a palisade. Palisades were made with large logs set upright in the ground and included watchtowers at the corners called sconces or flankarts, and gates secured with bars and bolts.

Major Walderne’s garrison (ca. 1664) was located on the site of the present Old County Courthouse on Second Street, Richard Otis’ on a 50-acre grant just off Central Avenue (then called “The Cartway”) near the corner of Milk and Mount Vernon Streets, Widow Heard’s on the slopes of Great (now Garrison) Hill, Peter Coffin’s near the present Firehouse Restaurant on Orchard Street, and Tristam Coffin’s located somewhere between Nelson Street and the old Belknap School.

The residents of Cochecho, now over 200 strong, grew more and more distressed at the uneasy peace with the Kancamagus-led Indians. The native population had been largely infiltrated during the 1680s by the more militant Indians who had fled war-torn Massachusetts. “The nightly refuge was always the blockhouse, and men hoed the fields the rifle close at hand.” Larger numbers of Indians, many with strange faces, were seen in town during the spring of 1689, and their close examination of the colonists’ defenses caused much alarm.

Yet Major Walderne, busy with his business and political life, scoffed at the villagers’ fears: “Go plant your pumpkins,” he is said to have remarked, “I could assemble one hundred men by lifting up my finger.”

During early June, some of the loyal old squaws, who knew of the Indians’ massacre plans, tried to warn the major once again. They would enter his garrison and chant:

“Oh Major Waldron, you great sagamore,

What will you do, Indians at your door.”

But again the warnings were not heeded. Information

About the impending attack reached military headquarters in Chelmsford on June 22, and a letter was dispatched from Gov. Bradford to Walderne on June 27:

“…some Indians…report that there is a gathering of some Indians in or about Penecooke with designe of mischief to English, amongst the said Indians one Hawkins (Kankamagus) is said to be a principal designer, and that they have a particular designe against yourself and Mr. Peter Coffin which the Council thought it necessary presently to dispatch Advice Thereof to give you notice that you take care of your own Safeguard, they intending to endeavor to betray you on a pretention of trade. Please forthwith to Signify the import hereof to Mr. Coffin and others as you may think necessary, and Advise of what Information you may receive at any time of the Indians motions.

By order in Councill for Major Rich’d Waldron

and Mr. Peter Coffin or Either of them. At

Cochecha: these with all possible speed.”

The letter would arrive on June 28, one day too late.

For on the evening of June 27, 1689, several squaws asked for the night’s shelter at each of the garrison houses. As this was a fairly common practice in peacetime, the women were admitted into Walderne’s, Heard’s, Peter Coffin’s, and Otis’ homes. At their own request, they were shown how to open the doors and gates in case they wished to leave during the night. No watch was kept and all the Cochecho families retired for the night.

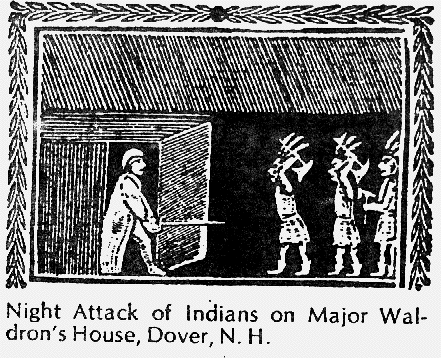

In the early hours of June 28, the squaws quietly opened the gates and admitted several hundred Penacooks into the undefended garrisons.

At Richard Walderne’s garrison, the Indians rushed into the major’s chamber. Still agile at age 74, Walderne attempted to fight the intruders with his sword, but was quickly overpowered and tied harshly to a chair. Each Indian then cut the major once across his chest with a knife while crying, “I cross out my account.” Cutting off his nose and ears, the Indians thrust them into his mouth then forced Walderne to fall dying upon his own sword. After his death, one hand was severed form the major’s wrist as retribution for those many instances when that first bore down unfairly on the weighing scales during trading deals with the local tribes. The Walderne garrison was then burned to the ground and the rest of Walderne’s family either murdered or taken captive.

Night attack of Indians on Major Waldron’s House, Dover, N.H.

At Richard Otis’ garrison, the scene was similar. The 64-year old blacksmith was killed as were his son Stephen and daughter Hannah. His third wife Grizel and three-month old daughter Margaret and two of his grandchildren were carried captives to Canada. Little Margaret (rechristened Christine and raised by French nuns in Quebec) would later return to Dover at age 45 with her second husband Captain Thomas Baker and open a house of Public Entertainment in Tuttle Square from 1735—1753. (Detailed accounts of Christine Otis Baker’s extraordinary life can be found at Dover Public Library.)

The Otis garrison was subsequently burned by the Penacooks only to be rediscovered in 1911. Workmen digging a foundation on Mount Vernon Street struck the remnants of a large brick chimney and some charred timbers. Careful excavation revealed such treasures as clay pipes and spoons, keys, bolts, nails, barrel hoops, a tomahawk, blacksmith’s punches and an ox-shoe, pieces of crockery, the bow of a pair of spectacles, brass buckles, and human and animal bones. Many of these historical relics are now on display in the Damme Garrison at the Woodman Institute.

The Heard garrison on the slopes of Great (Garrison) Hill, was defended by Elder William Wentworth, who had been guarding the property in the absence of its owner, Elizabeth Heard. Elder Wentworth was awakened to the Indians’ approach by a barking dog and managed to hold fast the gates against attack. This was the only garrison to be left totally unscathed that night. (The Heard house was in use as a dwelling until at least 1725 and was possibly torn down ca. 1745.)

But even more remarkable than the survival of the building was the survival of its owner. Elizabeth Heard with her three sons Benjamin, Samuel, and Tristam, their wives and families, and her daughter Mary and her husband John Ham, had sailed the previous day to Portsmouth and were returning with the tide just before dawn to Cocheco. After landing their vessel and finding the Main Street docks strangely deserted they cautiously made for the nearest garrison, Walderne’s. As they approached, the smell of smoke and the sound of Indian war cries alerted their senses to the grave danger.

One of the boys carefully skirted the palisade, climbed the wall and peered inside, only to see armed Indians standing guard in front of the burning house.

Mrs. Heard, so overcame with fright that she could not go on, begged her family to hide her in the bushes and to flee for their lives. Grudgingly, they obeyed her wishes and escaped safely to the Gerrish garrison at Back River. As daylight broke, an Indian leaving the compound spotted Mrs. Heard in the nearby thicket and she imagined her life was over. As he raised his pistol toward her, he suddenly stared hard at her face then turned and ran away, never revealing her location to the others.

As it happened, this Indian was one of the fugitives from the 1676 “sham battle” to whom Mrs. Heard had given refuge from capture. He had never forgotten her kindness and took this opportunity to repay the favor.

Window Heard remained in hiding until the Indians left Cochecho, then she walked to her own garrison expecting to see ruins there also. Instead she found her home and her family intact, defended by her brave neighbor William Wentworth.

Across the Cocheco River to the south stood the two Coffin garrison’s: Peter’s on Orchard Street (built ca. 1650) and Tristam’s near Nelson Street. With the squaws opening the gates, the Indians quickly overtook the Peter Coffin garrison. But became of Coffin’s past friendly relations and humane treatment of the Penacook, his home was not burned, merely looted. Peter and his family were taken captive however, and brought to son Tristam’s garrison a few rods south.

Tristam’s home was so well fortified that the Indians had not been successful in penetrating its walls. Holding Peter as a hostage at his son’s gates with a threat to kill him if they were not admitted, Kancamagus’ men forced Tristam Coffin to surrender also. Again, this garrison was not burned but was extensively pillaged. Both Coffin families were left captive in a deserted house, but while the Indians were busy plundering their homes, all the Coffins safely escaped.

Five or six more homes were burned as were mills at the Lower falls. Twenty-three people were killed and twenty-nine taken captive. On the morning after the massacre, survivors searched the town thoroughly, but the enemy had vanished. Swift pursuit resulted in the re-capture of three Otis daughters in the town of Conway. Added military aid from Massachusetts was soon dispatched to Cochecho, but no further attack was made.

Several years passed before Cochecho fully recovered. Houses and mills were rebuilt, but the loss of so many persons (about 25% of the population) was a severe blow to the settlement’s prosperity. By 1700 however, the town had begun to resume its former importance and though occasionally harassed by Indians, Cochecho was never again the target of so destructive and savage an act.

For the next sixty years, Indians raids continued to plague many other nearby seacoast towns in New Hampshire and Maine: Oyster River, Salmon Falls, Lee, York, Eliot, Exeter, Kingston, Newmarket, Rochester, and Nottingham all suffered tragedies similar to Cochecho’s. Yet, by the middle of the 18th century, disease, famine, and the “white tide” had all taken their toll on the Indian population of New Hampshire. By 1770, hardly an Indian remained in the Province.  For more information on indigenous people in the Dover area, look at these books available at the Dover Public Library and the listed websites.

For more information on indigenous people in the Dover area, look at these books available at the Dover Public Library and the listed websites.

Belknap, Jeremy, Belknap's History of New Hampshire: an Account of the State in 1792. Hampton, N.H., P. E. Randall,1973.

Brooks, Lisa Tanya, Our Beloved Kin : a New History of King Philip's War. New Haven : Yale University Press, 2018. https://www.ourbelovedkin.com/awikhigan/index (enter Waldron into the search engine) The Captivity at Cocheco William Waldron's Defense:The Capture and Return of Wabanaki Noncombatants

Bruchac, Jesse Bowman, Abenaki Dictionary. Greenfield Center, NY: Bowman Books, 2019.

Calloway, Colin G., Dawnland Encounters : Indians and Europeans in Northern New England. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1991.

Colby, Solon B., Colby's Indian History: Antiquities of the New Hampshire Indians and Their Neighbors. Exeter, N.H. : Colby, 1975.

Goody, Robert, A Deep Presence: 13,000 years of Native American history. Portsmouth, NH : Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2021.

Hardesty, Jared Ross, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. Amherst, MA, 2019.

Heald, Bruce, A History of the New Hampshire Abenaki. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014.

Masta, Henry Lorne, Abenaki Indian Legends, Grammar and Place Names. Toronto, 2008.

Norton, Mary Beth, In the Devil's Snare: the Salem witchcraft crisis of 1692. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Parker, Trudy Ann, Aunt Sarah: Woman of the Dawnland. Lancaster, NH: Dawnland Publications, 1994.

Piotrowski, Thaddeus, Indian Heritage of New Hampshire and Northern New England. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, c2002.

Scales, John, Historical Memoranda Concerning Persons & Places in Old Dover, N.H. Dover, N.H.: 1900.

Scales, John, History of Dover, New Hampshire. Containing historical genealogical and industrial data of its early settlers, their struggles and triumphs. Manchester, N.H.: Clarke, 1923.

Senier, Siobhan, Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

Warren, Wendy, New England bound : slavery and colonization in early America. New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016.

Wiseman, Frederick Matthew, The Voice of the Dawn : an Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2001.

Indigenous People of Piscataqua Watershed: A Dover400 Lecture

This online presentation is the first session in the Dover400 2021 lecture series, and pays tribute to the Native people who occupied our region prior to colonization by white settlers.

The History of Manchester, formerly Derryfield, in New Hampshire; including that of ancient Amoskeag, or the middle Merrimack valley; together with the address, poem, and other proceedings, of the centennial celebration, of the incorporation of Derryfield; at Manchester, October 22, 1851. By Chandler Eastman Potter, 1856.

"The History of Concord, From Its First Grant in 1725 - To the Organization of the City Government In 1853, With a History of the Ancient Penacooks" By Nathaniel Bouton

by Benning W. Sanborn, 1856. Indian History

"History of Concord, New Hampshire From the Original Grant in Seventeen Hundred and Twenty-Five to the Opening of the Twentieth Century" Prepared Under the Supervision of the City History Commission, James O. Lyford, Editor, 1903. Aboriginal Occupation

Legends of America: The Pennacook Tribe

Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People

Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective

From the Fragments: The Places and Faces of Great Bay Archaeological Survey

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.