Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

1992 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet June 1992 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1992.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

Pine Hill Cemetery

Pine Hill Cemetery

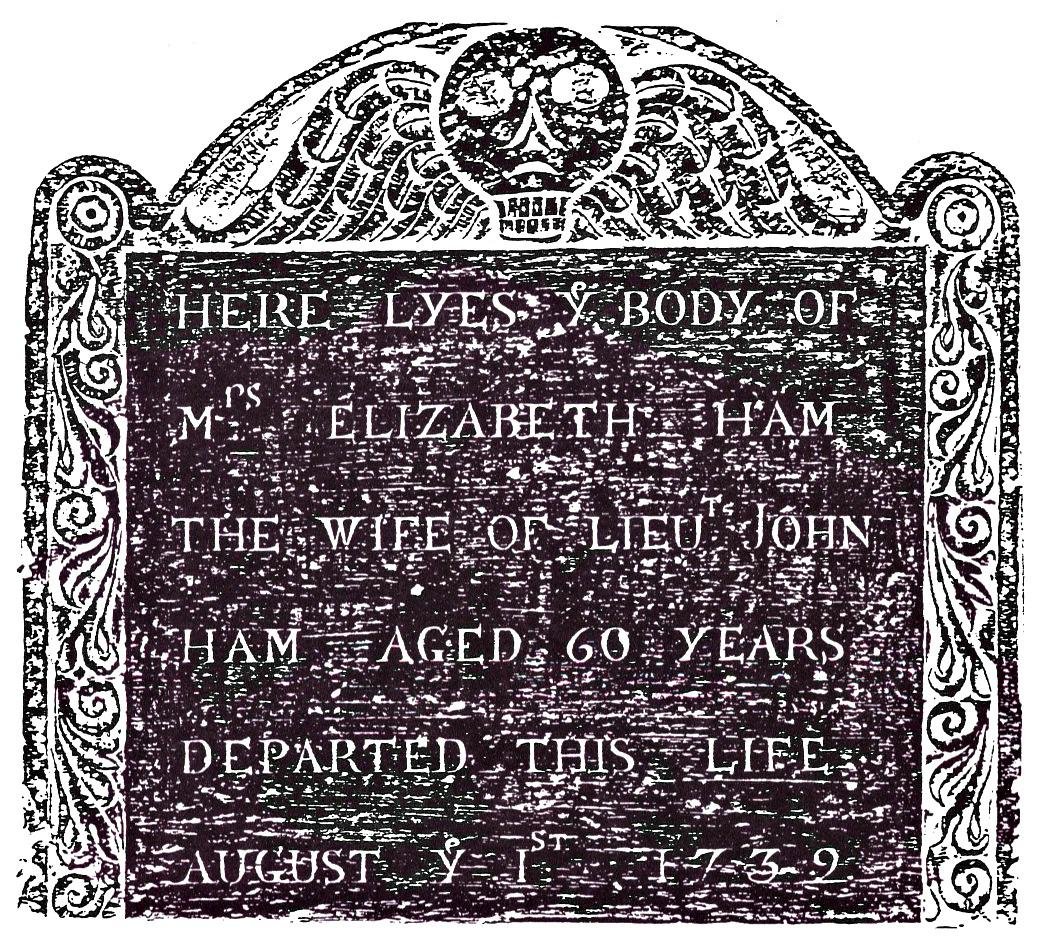

The Stories Stones Tell: Gravestone Art

Early New England gravestones are unique expression of primitive art: a reflection of the beliefs, philosophies, and fashions of the 17th and 18th centuries uniquely expressed in stone.

A largely illiterate population was taught about man’s confrontation with death and the afterlife through this art form, New England’s earliest form of creative sculpture. The images carved on the fieldstones and the slate slabs were intended not only to honor the dead, but also to teach lessons to those still living.

The close proximity of burying-grounds to church meetinghouses was fuel for many “fire and brimstone” sermons by New England’s first Puritan ministers. In fact, gravestone art was the only image-making indulgence allowed by the stern Puritan congregation because the symbolism of the carved icons was seen as a concrete way to convey the message of the mortality of man and the blessings of heaven. All the minister had to do was point outside the meetinghouse windows to illustrate his point about the certainty of death.

Indeed, the earliest examples of gravestone art (ca. 1620—1700 and not seen at Pine Hill Cemetery) are laden with disturbing, frightening images of winged “death’s heads” and skulls and skeletons. Usually portrayed with lifeless eyes and toothful grin, this death’s heads reflected the beliefs of a people who suffered the rigors of a severe climate, famine, epidemics, and Indians. Death was a fearsome and often sudden, prospect. So it is not surprising to see images of the grim reaper snuffing out the candle of life, or hollow-eyed grinning skulls beckoning to passerby with the now famous epitaph:

As you are now, So once was I.

As I am now, So you must be.

So prepare for death. And follow me.

These 17th century stones reinforced the inevitability of our mortal end, emphasized life’s brevity, and highlighted the awesome power of death. They were also symbolic of the belief that death was final, the ultimate end, death triumphant!

During the early years of the 18th century (about the time Pine Hill Cemetery was begun), changing religious attitudes and the influence of other sects such as the Congregationalists and the Quakers were responsible for the portrayal of less formidable figures and designs. The frightful death’s head evolved into a “soul effigy,” its features rounded out and softened.

By the 1750s the sorrowful soul had become a “winged cherub” and death was viewed not as “the end” but rather as a time when the soul lifted upward to heaven where it would dwell with the Lord.

The quality of materials and workmanship improved greatly during this century too. Whereas the earliest graves were carved out of raw roughhewn fieldstones with little added decoration or artistic finesse, by the early 1700s slate quarries were operating in New England and the close grained quality of fine slate allowed for minute detailing and more delicate carving styles. Where stonecutting was originally a part-time job usually done by hand craftsmen like woodcarvers, cordwainers, masons, bricklayers, slaters and surveyors, the growing population meant, of course, more deaths and stonecutters could be assured of steady work year round. Historians have traced many of the prominent stone cutters of early New England, their work identifiable by the peculiarities of carving a particular letter, similar phrasing or epitaphs, or a fondness for specific image, symbol or decorative element.

Stonecutters sometimes cut their initials into the base of the monument and often reused old stones where traces of an even older death notice can be deciphered under the newer carving. Marble was not popular as gravestone material until the late 1700s, but quartzite and sandstone were used extensively.

At one time it was believed that the stones came from England, imported here as ballast in ships crossing the Atlantic. But 20th century geological investigations have proved that almost all New England gravestones were “harvested” right here. The overall shape of a gravestone has varied little throughout history: they were meant to suggest a doorway to heaven or a passageway to the unknown.

By the early part of the 19th century, the winged cherub had evolved further into a full-blown angel and sometimes into a stylized portrait representation of the deceased. (At times, it is difficult to determine whether the figure is just an angel or the stonecutter’s portrayal of the loved one.)

More and more symbols were used in the 1800s and by 1815 the primitive nature of the early stones had disappeared, replaced by the neoclassical style. Gravestones were influenced by the architectural motifs of the Federal and Greek Revival periods: images of classical urns and medallions, graceful swags, and Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian pilasters were artfully etched onto marble and slate. The different symbols on 19th century gravestones can be classified into five groups:

I. Recognition of the Flight of Time:

Hourglass with sands of time run out

Hourglass with wings (swift passage of time)

Father Time holding a scythe

Candle with snuffer

Flower with stem broken in half

II. Certainty of Death:

Coffins (death of the flesh)

Urns (material remains)

Darts, arrows, or javelins (suddenness)

Pickax or spade (burial rites)

Crowing cock (repentance)

Gourds (passing away of earthly life)

III. Stating in Life/Occupation:

Coat of arms

Military trappings or insignia

Ship (for a captain, sailor or Navy man)

Minister’s collar

Scallop shell (a Pilgrim)

Depiction of how death occurred (e.g. amputated limb)

IV. Relating to Christian Life:

Grapevine (Christ)

Corn & grapes (body and blood of Christ)

Dove on a vine (dove=constancy & devotion; partaking of celestial food)

Squirrel cracking a nut (religious meditation)

Mermaid (half fish/half human just as Jesus was half man/ half God)

V. Foretelling of the Resurrection / Activities of the Released Soul

Pomegranates

Rising sun Resurrection is coming

Elevated torch

Flame rising from urn

Moon & stars

Fig (prosperity & happiness in the world to come)

Trumpet (“trumpet shall sound & the dead be raised”)

Crown (victorious soul)

Serpent with tail in mouth (eternity & immortality)

Willow (mourning for earthly life as well as joy over heavenly life gained)

Redeemed spirit emerging from a tomb

Soul effigy floating in space playing some musical instrument

In addition to these visual symbols, the embellishments and decorations on the tombstones grew fancier also. Stonecutters copied the ornate scrolls they saw on furniture imported from the Continent and sometimes filled every spare inch on a stone with curlicues or repeating geometric patterns.

The evolution of gravestone art reflects the growth of our national history as well. As we graduated from simple institutions to complex government and from living just well enough to survive to a focus on embellishing our lives with goods and possessions, our cemeteries subtly echo those cultural changes as well. Armed with some knowledge about the stories these stones tell, we can walk around Pine Hill Cemetery and absorb some of the history of Dover.

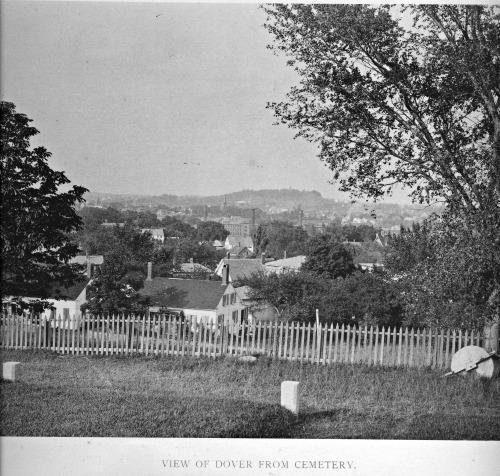

Pine Hill Cemetery

From the time of its settlement in 1623, Dover’s inhabitants were buried, after their deaths, in family plots located primarily in the Dover Point, Dover Neck, and Spruce Lane/Garrison Road regions of the town. Family members were interred on their own land in small cemeteries marked by fragile fieldstones. Many of these graveyards have disappeared stones broken and graves unidentified, often turned under by the developers’ shovels.

The late Roy Ackerman, long time member of the cemetery Board and active historic preservationist, compiled, in 1988, a listing of the gravestones contained in over fifty family lots around Dover. This list is available in the Historical Room at the Dover Public Library.

After the establishment of the First Parish Congregational Meetinghouse on Dover Point in 1634, the idea of burying the dead in a communal place slowly gained favor. Dover’s oldest community cemetery can still be viewed on Dover Point Road at the site of the second Congregational Meetinghouse which was built ca. 1658 (and estimated to be about one mile north of the first “unknown” site).

As the population of the “Cocheco” grew during the latter half of the 17th century, the center of activity slowly moved north from the Point. Richard Waldron had begun using water power at the Lower Falls of the Cocheco River to run his sawmill and the town evolved further at “The Landing” with a developing shipping industry. With two growing population centers, the elders of the Congregational Church built a third meeting house almost equidistant from the Point at the south end and the Landing at the north. This third house of assembly was built at Pine Hill(near what is now the Cushing Tomb)ca. 1710. For about a decade, ministers preached at both meetinghouse locations, but finally made a permanent move to Pine Hill house in 1720. This new location had been used a burial ground by the local Indians for two earlier centuries and was known as “The Pines.”

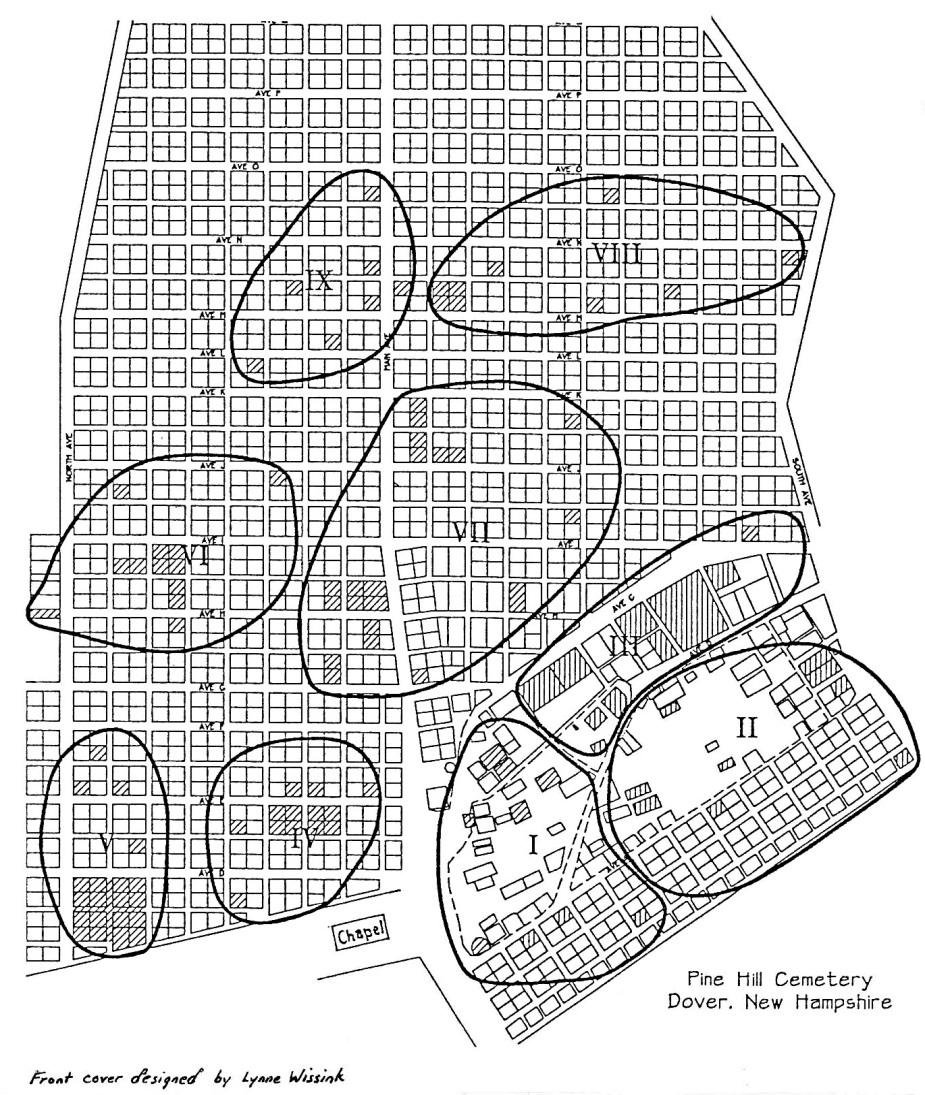

Pine Hill was officially established as the town cemetery on March 29, 1731. It was voted at a public town meeting to set aside 1.5 acres “for a publick Burying-place to be laid out by ye Selectmen near ye Meeting-house on Pine Hill at Cocheca.”

In 1758, the meetinghouse for the First Parish Church moved again to its present location of Central Avenue. Burials continued at Pine Hill, however there was little organization or management and haphazard arrangements soon developed.

More than half a century passed before the town of Dover saw fit to improve conditions at the cemetery. During the 1830s, John P. Hale proposed a sum to repair fences, make improvements, establish some regulations, and choose a superintendent. He cited the “ruinous and neglected condition,” and “grounds intersected with carriage and foot paths.” Hale further noted that “individuals who wish to protect the graves… have resorted to the plan of making small enclosures inside the yard” to protect their plots and keep others from trampling on them. A committee formed to investigate these complaints found 34 such enclosures surrounding 5347 square feet of land: small fenced-off cemeteries within the cemetery.

In 1840, Hale’s committee suggested that the grounds be enlarged and graded, that plantings of shrubs and trees implemented, and that a plan of the whole yard be drawn up including the surveying, numbering, and dividing of all lots into 16’ X 20’ spaces. They also encouraged the town to lay out specific carriage paths and to disallow all enclosures. Hale asserted that all this could be done for $350 and this appropriation $150 was spent for “finishing the improvements” but no superintendent was ever hired until 1895.

From 1855 (when Dover was incorporated as a city) until 1895 the management of Pine Hill Cemetery lay with the Joint Standing Committee on Cemeteries, consisting of two councilmen and one alderman. The size of the grounds increased gradually during the mid-19th century. Small purchases of land bordering the cemetery were made of Elizabeth and Lydia Watson (24 sq. rods), Daniel Osborne (47 sq. rods), and William Woodman (62.5 sq. rods).

In 1870, Osborne conveyed the land west of Avenue F to the Grand Army of the Republic’s (G.A.R.) Charles W. Sawyer Post #17. In 1886, the G.A.R. sold this land to the city for $1.00. Land west of the Court Street entrance was purchased in 1892 from John brown ($570) and Patrick Cragin ($630).

The City of Dover changed the management of the cemetery in 1895. They replaced the Joint Standing Committee (who were elected officials) with an appointed Board of Trustees with staggered terms for continuity. They felt that “continual change cannot be productive of the best results.” The new Board was charged with initiating “a well-defined and permanent policy for progressive and economical development.” Its first members were William S. Stevens, Hiram F. Snow, and Charles H. Sawyer, Elisha Rhodes Brown, Henry Law, and (ex officio) Mayor Alonzo M. Foss. Treasurer was B. Frank Nealley. These men promptly hired a superintendent, Frank P. Coleman, at a $382 annual salary and supplied him with a horse at a cost of $118.50.

The trustees set up new rules and regulations that included: no mounds higher than four inches may be built over graves, no flower picking, no noisy or disorderly conduct, and no discharged of firearms expect in a military salute. The Board also discouraged the building of vaults “believing, with the best landscape gardeners of the day, that they are generally injurious to the appearance of the grounds and… are apt to leak, and are liable to rapid decay…and become unsightly ruins.”

Since that time additional land was purchased and Pine Hill cemetery now covers 75 acres, of which about 60 acres are in use. Superintendent Nancy Gagne directs a staff of three permanent and six seasonal employees and burials are done year-round. The grounds contain over 7.5. miles of road, avenues, paths, and lanes, and estimates say that approximately 25,000 people are buried in Pine Hill Cemetery: this equals the current population of Dover!

1992 Cemetery Board members Grover Tasker, William Kincaid, Belinda Campbell, and Russell Newell oversee a FY’92 operating budget of $148,882. As listed in the city’s 1990-91 Annual Report, 66 regular interments, 18 cremation burials, and four entombments took place last year. In addition, there were 60 foundations erected and 45 graves sold.

OTHER NEARBY BUILDINGS:

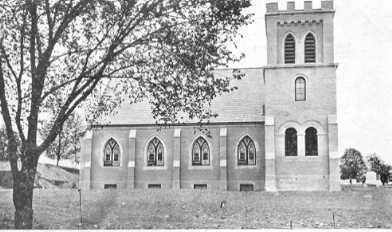

Ricker Memorial Chapel

Ricker Memorial Chapel was a gift to the city from the will of Mary Abby (Ham) Ricker who died in 1906. The chapel was erected in memory of her deceased daughter, Mary Edith ‘Mamie’ (Ricker) Gallagher who died of peritonitis at age 34 in 1895 after falling from her horse.

The chapel’s cornerstone was laid November 10, 1911, and the A.T. Ramsdell-designed building was completed the following spring. At formal ceremonies on September 29, 1912, the small church was conveyed to the city by the will’s executor, Mr. Fernald, who presented the keys to Dover mayor Dwight Hall. Fernald noted that of the 140,000 bricks used on construction 100,000 were made here in Dover.

Fernald also remarked on the growth of the cemetery, complimenting Supt. Frank Coleman on his success with a greenhouse built on the Court Street side of the cemetery where Coleman was raising 2000 geranium plants and 50 hydrangea bushes. Executor Fernald also congratulated the Board of trustees, mentioning that Pine Hill cemetery had grown by 30 acres during the past 17 years and that the Perpetual Care Account now stood at $50,000, up from only $1500 when the board was created in 1895. He proclaimed the Ricker memorial Chapel as the crowning glory for the cemetery and a fitting bequest from the late Mrs. Ricker.

Originally used for funeral services, the chapel’s use declined when funeral homes began to offer such facilities. Use was also minimal in cold weather as the chapel had no heat. Its condition was neglected for years and it was often ransacked by vandals. In 1967, extensive repairs and renovations were made to the deteriorating building and oil heat was installed. Today, the Ricker memorial Chapel is open only for special occasions and is not used for individual burial rites.

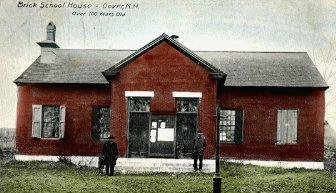

Pine Hill Schoolhouse

Immediately to the left of the cemetery entrance is the site of three Pine Hill Schoolhouses, the first a small wooden structure built in 1712. This was replaced by a two room wood frame school in 1790. A brick school, housing half primary and half secondary students, replaced the wooden building in 1824. Many generations of Dover students attended classes here, yet by 1904 only 40 students, one 5th grade and one 6th grade class were housed here.

Additionally, the buildings were used as a ward House at election times for about 35 years. This was disruptive to the pupils and teachers and in 1905 its use as a school stopped. The building was abandoned and eventually condemned. It was transferred to the Cemetery Department in 1912. Workers there demolished it and extended the granite wall on Central Avenue northerly the entire length of the newly acquired property. Also at this time the grounds were graded to bring the new Ricker memorial Chapel into relief.

Friends Meetinghouse (Quaker)

Located at 141 Central Avenue, the Dover Society of Friends Meetinghouse was raised in June, 1768. It is the oldest religious structure in Dover and a fine example of early post and beam architecture. It is the third meeting house of the Friends and for many years was the largest assembly hall in Dover.

The entrance contains two doors, the left originally leading to the women’s side, the right to the men’s. The segregated sections were used for separate, but equal, business meetings. The partitions dividing the sexes could, however, be removed for joint worship. Presently, one side remains in its original form for meeting for worship while the other side houses a library and a small kitchen area.

The woodframe building, with a balcony story (now closed off), measures 30’ x 50’. With its large beams, thick walls and timbers fastened with wooden pins, the meetinghouse remains largely as it was during Colonial times.

No preacher or pulpit was used during Quaker services. Instead, silence was the rule so that God might inspire each individual directly. There was no music or readings: if a member received a message, (s)he would rise and explain it to the congregation.

John Greenleaf Whittier often attended meetings were as a child when visiting his grandmother at the Hussey Farm on the outskirts of Dover. His parents, John Whittier and Abigail Hussey, were married here in 1804.

Although one-third of Dover’s population was Quaker in the 1680s, by 1912 regular Sunday meetings had ceased and the building was open only once a year, usually on Fast Day in April. The meetinghouse reopened in 1955 for Dover’s Centennial celebration, and Friends’ meetings for worship and business meetings are now regularly held here.

The meetinghouse was raised once again in 1989 to excavate for more space and to add an entrance for the handicapped. This additional basement space is now used for the expanded Sunday school program.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bodor, John j. Rubbings and Textures: A Graphic Technique.

New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1968.

Forbes, Harriette Merrifield. Gravestones of Early New England and the Men Who Made Them, 1653—1800.

Princeton, N.J.: Pyne Press, 1927.

Gillon, Edmund Vincent Jr. Early New England Gravestone Rubbings.

New York: Dover Publications, 1966.

Jacobs, G. Walker. Stranger Stop and Cast An Eye: A Guide to Gravestones and Gravestones Rubbing.

Brattleboro, Vt.: Stephen Greene Press, 1972.

A Legend in Stone. Creative Crafts (June 1981), 52-54.

Mann, Thomas C. and Greene, Janet. Over Their Dead Bodies.

Brattleboro, Vt.: Stephen Green Press, 1962.

Wallis, Charles L. Stories on Stone.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1954.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.