Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

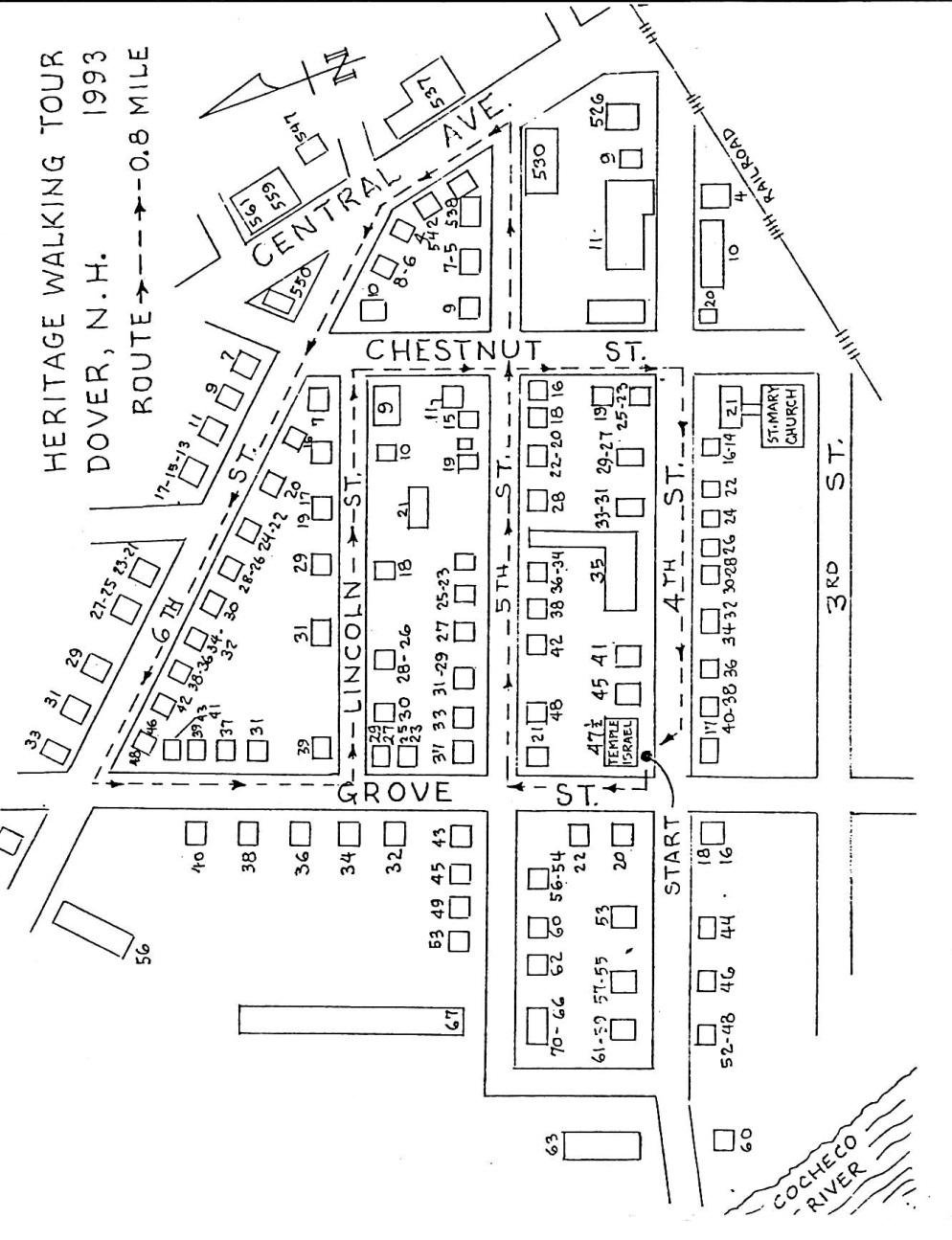

1993 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet October 1993 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1993.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

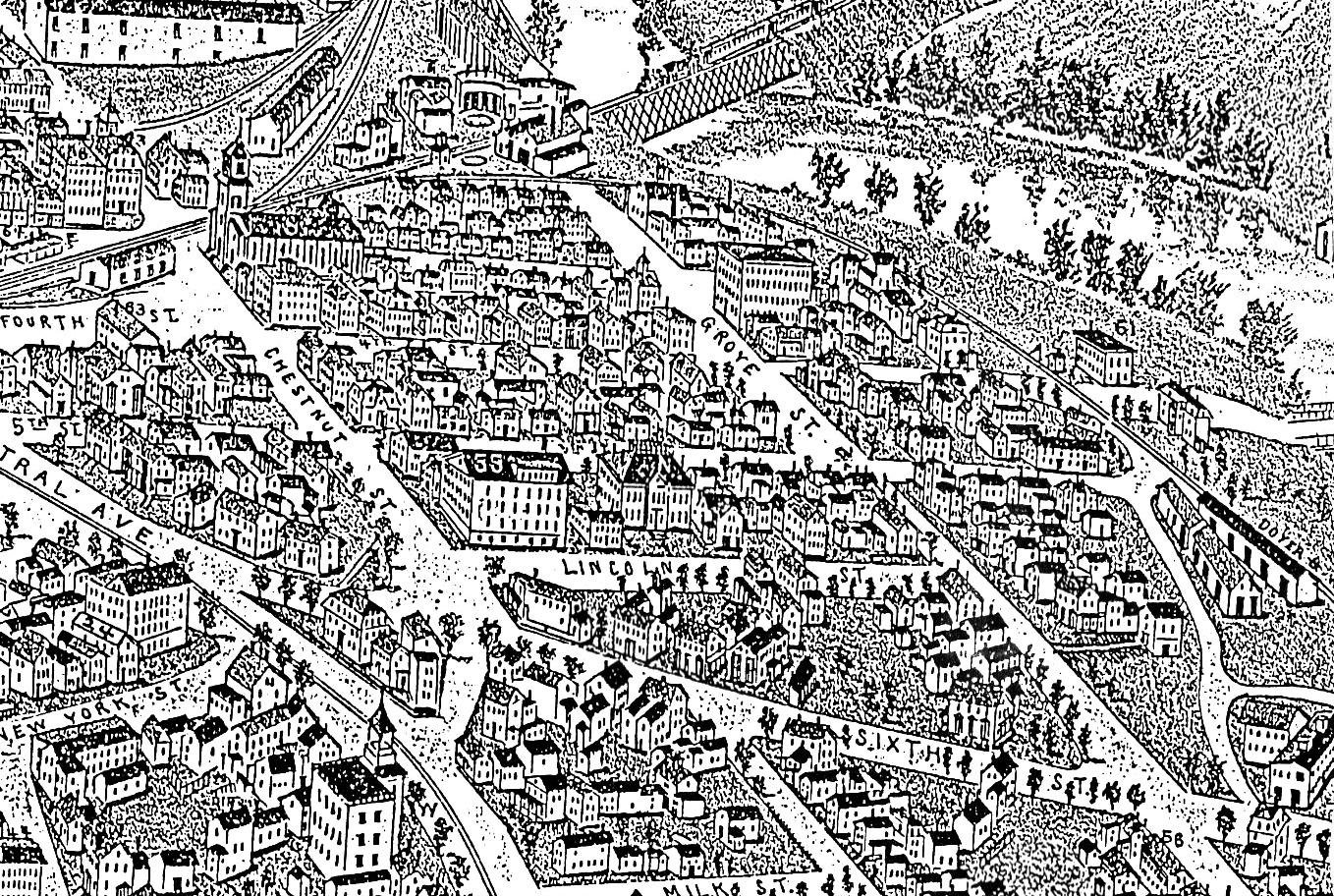

The evolution of the neighborhood encompassing Fourth, Fifth, Lincoln, Sixth, and Chestnut Streets and bordered by Grove Street and Central Avenue began nearly 175 years ago when owners of the Dover Cotton Factory purchased 135 acres of farmland in this part of town from the bank which had foreclosed on the mortgage of Daniel Waldron (ending 180 years of Waldron possession).

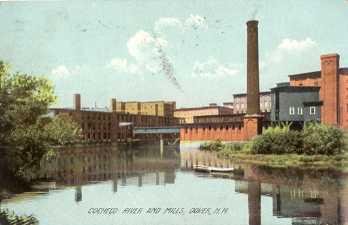

During the 1820s, five parallel streets from Front (now First) to Fifth were laid out in an east-west direction and Back (Grove) and Chestnut Streets bisected them north and south. Sixth Street already existed, known originally as Horne Road and by 1831 as Brick Street. It was three miles up Horne Road to the Upper Factory, Dover’s first cotton-producing mill which was built by John Williams in 1814 at the fourth falls of the Cocheco River. The Upper Factory area eventually grew to over 300 residents who formed a community they named “Williamsville.” Single-family homes, boarding houses, stores, and a 30-pupil school thrived here until the 1840s. In 1849, the Upper Factory was torn down to clear the way for the Cocheco Railroad and many of the houses were moved into town. Brick Street became Sixth in 1855 when Dover became a city.

The Cocheco Manufacturing Company (the name was changed in 1827) divided most of its land in the First-to-Fifth area into house lots. The growth of the factories at the Lower Falls (now downtown Dover) from 1822—1826 had been tremendous: five giant mills employing about 800 females and 300 males. The population of Dover had increased from 2871 to 5449 in just ten years. Newspaper advertisements had attracted hundreds of young girls from small N.H. and southern Maine towns to work for good wages in Dover’s cotton mills. And, as all these employees would need places to live when they got here, the Company entered the housing market. Dozens of factory-sponsored boarding houses began operating in Dover. Like single-sex dormitories, and predominately female, these establishments were run by older women, usually widows, who enforced strict rules of conduct and deportment. Yet in the Cocheco system, other types of housing were offered as well: company-built duplexes and single-family homes were available for low rent in the decent neighborhoods close to job sites.

For the skilled weaver or engraver or foreman, the residential enticements had to be good. Cocheco was in constant competition with factories in Newmarket and Great Falls for these trained workers and the offer of good wages was often not enough.

And when, in 1826, Agent Williams wanted Cocheco to augment its successful cotton cloth production with a risky calico printing operation, he knew he would have a hard sell getting experienced printers to relocate to Dover. The process of block printing patterns on cotton was a fledgling and untested industry in the U.S. and the other only printer was in Rhode Island. So John Williams went to England, toured Sir Robert Peel’s factories and convinced five knowledgeable calico printers to emigrate here to become his superintendents.

In 1827, Williams resourcefully created eleven “flats” on Fifth Street out of a pre-existing building: “The long shed…has been sawed into pieces thirty feet, being eleven of them which were removed and placed over cellars on Fifth Street where they will make a very pretty collection of cottages for our workmen, and applications are frequently making for them. They are now finishing under contract having two respectable rooms with closets and other conveniences and two small chambers above.” These homes were the first residences in our Heritage Walk neighborhood.

By 1830, nearly all the occupants of Fifth Street were of English origin and connected to the Cocheco Company: John Kimball, dyer; Joseph Lawton, pattern designer; John Delany, calico printer; William McCormack, block cutter; Michael Grant, bleacher; John Holland, cloth hanger. Some of these original homes (in most cased greatly altered) can still be seen at 21, 27, 33, 38, and 42 Fifth Street, which perhaps the best example being the small white house at 48 Fifth Street.

In 1831, the Cocheco Manufacturing Company officially mapped its lots from First to Brick Streets and surveyor Alexander Wadsworth numbered them 1 through 76. This plan clearly shows the eleven flats on Fifth Street and the Company’s woodyard (#18) on Third Street. Reproduced on the next page, the map is part of the 1834 Whitehouse Map of Dover. Notice there are still no houses on Back (Grove), Fourth, or Chestnut Streets and Lincoln Street does not even exist.

The cluster of buildings in the small block bordered by Chestnut, Brick, Franklin, and Fifth Streets and the adjacent structures facing Franklin Street just south of that block can be attributed to Joseph Morrill whose home is at the corner of Fifth and Franklin (now Dover Vision Center, 538 Central Avenue.)

Originally a weaver for the Cocheco Company, Joseph Morrill made his fortune in real estate. In 1827, he purchased all the land between Fifth and Sixth Streets from Cocheco for $900. He quickly sold the lots for profit and new homes were erected here. Morrill also built two huge commercial blocks at Franklin (Upper) Square in 1844 and 1870. He died in 1871 and left an estate valued at over $73,000.

After providing for its employees’ basic living necessities, another important, though intangible, amenity was astutely recognized by the Cocheco Manufacturing Company: spiritual life. There were only two churches in Dover in 1815, yet by 1840 there were tent. Part of this religious growth can be attributed to passage of the Toleration Act of 1819 which allowed religious freedom to those worshipping at non-government sanction churches. But another reason that four churches were established in our walk area between 1824 and 1828 was the Cocheco Company’s desire to keep their workers happy. Church attendance was a high point in the lives of people working for the mills. In fact, boarding house rules often required attendance at services. For many young women, the church provided a social life also: music and song, literature/discussion groups, religious education, and a legitimate place to meet similarly-minded young men in a suitable setting.

In most cases, land for each church was donated by the Company to the religious leaders with the caveat that should the edifice be used for anything but a church, the lot would revert back to the company. St. Aloysius (now St. Mary’s) Roman Catholic Church was dedicated at the corner of Third and Chestnut Streets in 1829. The Peirce Memorial Church (Universalist) was organized in 1825, built on Third Street in 1837, moved to Central Avenue (where First Savings Bank is now) in 1882, and torn down in 1976. Members of the First Free Will Baptist Church assembled at the Upper Factory for worship in 1824 and built their church in 1830 at the corner of (now) Lincoln and Chestnut Streets. At its dedication in 1832 Rev. A. Caverno stated, “The strength and efficiency of the church was essentially in the women, who worked in the factories and who were the soul of the movement in building a house of worship.” This church was sold to a shoe shop in 1851 and the building is still here as Caswell’s Auto Parts. The Free Will Baptists moved to Broadway and disbanded in 1902.

Peirce Memorial Church

Peirce Memorial Church The fourth church in this neighborhood was also Baptist, but of the Calvinist sect. The Franklin Street Regular Baptist Church was given a lot on the corner of Fourth and Franklin in 1829 and built their church (#16 on the map) that same year. Their name was changed ca. 1878 to the Central Avenue Baptist Church and in 1918 they were consolidated with the Washington Street Free Will Baptist Church to form the Dover Baptist Church. The Central Avenue building was converted to a recreation hall, then became Flowers Furniture Store 1932—1966, and the Baptists’ adjacent chapel was rented to the Dover Chamber of Commerce from 1921—1936. It is the site of the present day Dunkin’ Donuts.

The next big change for this neighborhood began in 1842 when the Boston & Maine Railroad came to Dover. The passenger depot was built on Third Street and thus began the growth there of hotels, restaurants, and saloons catering to travelers. The railroad also precipitated a major change for the Cocheco Manufacturing Company. They were now able to bring in by rail the thousands of tons of coal they needed to feed the mills’ furnaces and steam-run machinery. The wood furnaces were scrapped and the eyesore woodyard on Third Street was closed. Businesses soon opened up in this converted space. Yet all the hustle and bustle on Third Street spilled over onto Fourth Street only in residential development, not commercial endeavors. Although the Cocheco Company sold the lots, very few of the early residents of Fourth Street worked for the company directly.

Homes built on Fourth Street were not the identical string of “factory houses” as on Fifth Street, but were individually styled and sized. This diversity of both architecture and occupation that manifested itself here is significant for this area. It was soon reflected in the whole neighborhood.

Dover’s population had grown to 8196 by 1850. There was an influx of Irish immigrants to the area; in fact, the neighborhood was derogatorily referred to as “Dublin.” The Cocheco Company had sold, in 1841, its Fifth Street flats to individual owners. Less than half the owners were now connected to the mills. Back (Grove) Street was starting to develop and many homeowners had located on Brick and Mt. Vernon Streets.

An important influence of the growth of the railroads and mills in Dover was that these major industries spawned dozens of smaller businesses. With a larger and more diverse population, all kinds of goods and services were demanded and provided. By 1850, our neighborhood housed bakers, barbers, painters, cordwainers, tailors and milliners, masons and carpenters, clerks and teachers, glaziers, tinworkers, druggists, insurance agents, peddlers and myriad other tradespeople.

Then, just around the middle of the 19th century, a new industry took hold in this part of Dover: shoe manufacturing. Up until this time, a boot or shoe was made throughout by one person who precisely measured the food of his customer: length, width around heel, ankle, and instep, around joints at toes “making allowances for corns and bunions” and then hunted through his pile of lasts for one the right length. Then the shoemaker glued on the pieces of leather till it made the exact shape of the foot. The cordwainer’s trade, often promoted door-to-door with whole families “footed out” at a time, ended in Dover in 1865 when John Goodwin and John S. Wheeler introduced steam-powered machinery at their shoe shop on Fourth Street: equipment that “could cut soles as rapidly as a dozen men could do by hand.”

The first shoe shop in Dover actually opened in 1847 at the corner of Sixth and Chestnut Streets. Cyrus E. and Samuel C. Hayes, brothers from Farmington (location of N.H.’s largest shoe shops) employed shoemakers to hand cut and prepare the leather stock which was then sent out to smaller shops for finishing. But most of Dover’s shoe manufacturers started just after the Civil War when homecoming soldiers provided an ample supply of labor. Some companies did not last long while others prospered into the 20th century. It is assumed that all the new machinery available for the mass production of large quantities of shoes had much to do in making or spoiling fortunes. Over a dozen shoe factories were in operation between Third and Sixth Streets by the 1870s. These factories moved around a lot within the neighborhood, changing names and affiliations as partners split and reunited with another. It was not unusual to find two competitors sharing the same factory.

Cyrus Hayes

Samuel Hayes

The major shop locations were at the corners of Chestnut and Third, Chestnut and Fourth, Chestnut and Lincoln, Chestnut and Sixth, and 10 Grove Street. And like the Hayes Brothers, most of the men who ran these shops: John H. Hurd, John E. Goodwin, Alvah Moulton, Jonathan Bradley, Ira W. Nute, and E.C. Kinnear came here from Farmington.

These shoe factories brought more residents to the area. A new street was laid out in 1861---Lincoln Street---named for newly inaugurated President Abraham Lincoln who had visited Dover in March 1860. Eliza Chamberlain and Uriah Wiggin were the major landholders here and each erected several multi-family homes. In the twelve residences that existed on Lincoln Street by the late 19th century lived as many as fifty families and individual boarders, most of whom worked in the shoe shops or the cotton mills.

One shoe shop outlasted all the others. In 1886, the Dover Improvement Association built a four story wooden structure 150’ X 45’ at the corner of Sixth and Grove Streets (50-60 Sixth St.) for Lewis W. Nute. Nute died in 1888 and the shop was rented to the Charles H. Moulton Shoe Company. They employed 200 and stayed there until ca. 1903. From 1905 to 1912, the firm of Luddy and Currier had their shoe manufacturing operations here and in 1909 they were joined by the Beckwith Box Toe Company who occupied the main section of the building. In 1913, the Farmington Shoe Company moved into the building on the west side of the property (the part still standing) and stayed until World War II. Beckwith was here until the 1950’s, then the Weiss-Lawrence Shoe Company was the last, closing in 1974. After neighbors voiced concerns that the now empty factory was a fire hazard, the main portion was torn down.

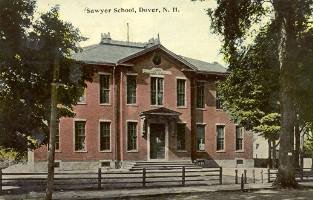

The neighborhood’s population growth in the second half of the 19th century meant, of course, more children growing up here. The small district schools that existed on Fourth and Brick Streets were insufficient and so, in 1870, “the most expensive school building in the city…and the best adapted to school purposes” was built for $30,000 between Fifth and Lincoln. The Sawyer Grammar School, with eight classrooms and room for 192 pupils, was named for the Hon. Thomas E. Sawyer of the Board of Education “who has been intimately connected with Dover school system for nearly half a century.” A major fire in 1890 destroyed much of the school, but it was rebuilt essentially as before. Disaster struck again, however, on June 30, 1979, when overheated basement wiring caught fire. This time the damage, estimated at $850,000, was irreparable. Just seven years before, in 1972, $140,000 had been spent on renovations to the building, including new wiring.

The school’s wood interior was gutted and the flames had burned through the roof. It was sold in November, 1979 to Michael Spinelli Jr. for $21,000. The top floor was removed to better blend in with the neighborhood and the 11-unit Sawyer School Apartments opened in September 1980.

During the latter years of the 19th century it appears that Chestnut Street became the dividing line between the classes. Those people who lived on the west side of Chestnut (in the direction of Grove) were the laborers and blue collar workers. Residents’ surnames on this side show the influence of immigration: Irish names filtered in first, then French and Greek in the 1890s and early 1900s.

But on the east side of Chestnut Street (toward Central Avenue) were the shop owners, company managers, and factory magnates. The home of Joseph Morrill, Isaac B. Williams owner of I.B. Williams Leather Belting (now Store 24), shoe manufacturers Ira Nute, John H. Leighton, and John Hurd (now Holmwood’s Decorating Center), and furniture store owner Edward Morrill (also now Holmwood’s) were all on the more exclusive side of the neighborhood, close to their businesses but certainly not next to the Fifth Street flats.

Ironically, these large old single-family manses are the ones that have been lost as commercial development has spread in from Central Avenue. Before they were torn down, most of the “grander” houses here had fallen into disrepair, converted into low-cost apartments and rooming houses (e.g. “The Elms”). The area between Chestnut and Central Avenue in the 20th century housed the Moose Lodge from 1940-1963 (now The Lost Whale shop), Swift and Company meat distributors 1920--1970, Sherwood Signs, and Varney Cleaners.

Tony’s Cyclery was a feed store before 1965, and the shoe factory on the corner of Fourth and Chestnut Streets became R.C. and H.G. Hayes Bottlers about 1890, then C.E. Brewster Wholesale Druggists ca. 1909. St. Mary’s bought the property around 1950.

The last major change to our Heritage Walk neighborhood occurred in 1938 with the construction, on Fourth Street, of Temple Israel, Dover’s Jewish synagogue. In 1952, the Jewish community of Dover had purchased the former Lincoln Inn on Nelson Street for use as a social hall and Hebrew School, but the distance between their two facilities was a continuing problem.

In 1967, it was learned that the two houses adjacent to the Temple at 45 and 47 Fourth Street were for sale. The social hall on Nelson Street was sold to the Knights of Columbus and the two houses on Fourth Street were purchased. #45 was renovated for the Rabbi’s home and #47 was torn down for Temple expansion.

A building committee devised plans for an addition to the original Temple to form an enlarged single multi-floor building 78’ X 56’. On the upper level would be the Sanctuary, classrooms, library and Rabbi’s office; on the lower level a general purpose meeting room and kitchen. Groundbreaking ceremonies took place on May 4, 1969 and formal dedication of the new facilities was celebrated on September 20, 1970.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.