Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

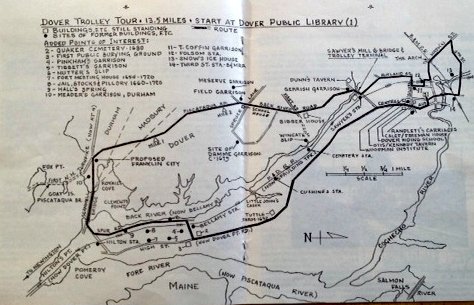

1995 Heritage Trolley Tour

Heritage Trolley Tour Booklet October 1995 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1995.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

River to rail to road, the network of routes that evolved and grew in Dover have marked both its successes and failures. The economy of the city has always been defined and maintained by its transportation. For the past four centuries, residential, industrial, and commercial successes all depended on a reliable means of transporting goods and people to, from, and within the city. Before there was a house to live in, or a factory to work in, or a shop to sell in, there had to be way to get there.

Therein lies the multi-faceted history of transportation in the city of Dover.

The Rivers

Dover Point/Dover Neck

Almost four centuries have elapsed since the Europeans first settled the land that was to become Dover. The location chosen by the first settlers at Hilton Point (now Dover Point) could not have been more advantageous. The area consisted of a wooded peninsula at the convergence of several rivers and the bay. At that time, waterways provided the main, if not only route of transportation. The first mode of transportation was most certainly the canoe, which for centuries was paddled by Natives on the rivers.

Dover Point

In 1623, Edward and William Hilton arrived in the ship “Providence” and landed at Pomeroy Cover at Dover Point. The first immigrants lived close to the original settlement at Dover Point. As the population increased, settlers gradually moved further up the peninsula of Dover Neck, which is the narrow strip of land between the Fore (now Piscataqua) River on the east, and Back (now Bellamy) on the west.

The first settlers were engaged in fishing, the original purpose of the settlement. Both banks of the settlement were lined with numerous slips, landings, and shipyards. Not only were there small shipyards for building small boats for citizens, but in 1661, a naval frigate was built at Dover Point for the British government. In Dover’s early history, shipping masts, dried fish, and beaver skins for Europe were the staples of the area’s economy. Lumber for barrels and casks was hewn at Dover sawmills and regularly shipped to the West Indies in trade for rum and spices. Dover Point thrived as a waterfront village for about 150 years, until the Industrial Revolution moved the center of activity to Cocheco River.

Back River/Bellamy River

Dover development began with the river egresses and Back River was an early route to access territory inland. In the 1640’s the west side of Back River had been sold as twenty acre lots. Houses were built as close to the water as feasible, with barns built behind them. John Drew purchased several lots in 1642, including marsh land near his “thatch bed”; evidently, the early houses had thatched roofs. Travel was by boat, as there were no roads in this area at that time.

Back River extended from Cedar Point to John’s Creek, Durham and Madbury. There were six garrisons in this neighborhood: Dam’s or Dame’s Garrison, (c. 1695) on Garrison road, Drew’s on Spruce Lane, Field’s opposite Back River Schoolhouse (mentioned in 1707), Meserve Garrison near Garrish Drew’s house, Torr’s west of Mast Bridge, near Simon Torr’s, Clark’s, (c.1690) near the border of Dover and Madbury, and Meader’s at Cedar Point, now within Durham town limits. The Garrisons were homes of prominent Doverites ordered to be fortified against Indian attack, or “garrisoned” and served as protection for local residents.

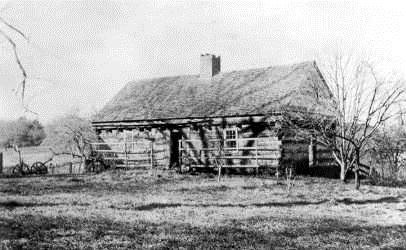

The Dam Garrison is the only surviving garrison of sixteen in this area. Built around 1675, it is the oldest building in Dover. Today it is sheltered under a protective canopy at the Woodman Institute, Dover’s historical museum. The 40’ x 22’ house was relocated from its original site over the course of one week in October 1915, moved by four men using rollers, and one horse doing the hauling.

Ferries

Dover Point Road, which generally follows the high ground between the Piscataqua (Fore) and Bellamy (Back) Rivers, was called High Street in earlier days. There were several lanes leading from High Street down to the river on both sides of Dover Neck. At the end of these roads was usually a boat slip, such as Hall’s Slip and Nutter’s Slip on the Back River, and Capt. Barefoot’s Slip (1652) and Beck’s Slip on the Fore River.

As early as 1637, ferries were operating on the rivers. One of these operated out of Hall’s Slip and ferried between Hilton Point and Bloody Point, which is now Newington. The first ferryman was Thomas Trickey, one of the first settlers in the Bloody Point area of Old Dover. Trickey also ran the ferry to Everett’s Point, Old Kittery. The Bloody Point Ferry was operated by the Trickey family for 68 years. On Dec. 18, 1705, Capt. John Knight, after purchasing Trickey’s farm and holdings, petitioned the NH General Assembly for a license to operate the Bloody Point ferry. It was “accordingly agreed that the Governor be desired to give him a patent for the said ferries, he not demanding more than twelve pence for each horse and man at each ferry and three pence for every single person without Horse, he always taking care that there be Boats ready, that there be no complaint thereupon.” It was operated by Capt. Knight until 1725, followed by the Henderson family until the early 1800’s. The Bloody Point ferry did not cease operation until the railroad bridge was built in 1871.

Near Hall’s Slip was Hall’s Spring, dating from 1633. This notable spring supplied the early sailing ships with sweet water for their water casks, noted because it would not get brackish during the six or eight weeks it would take to return to England.

Beginning in 1717, Nicholas Harford ran another ferry to Kittery. Harford’s Ferry ran across the Fore River from Beck’s Slip to Morrill’s Point on the Eliot shore, originally a part of Kittery. His fee for this service was twopence for a single person and sixpence for a man and a horse. Harford’s ferry ran until 1830.

The Cocheco/Gundalows

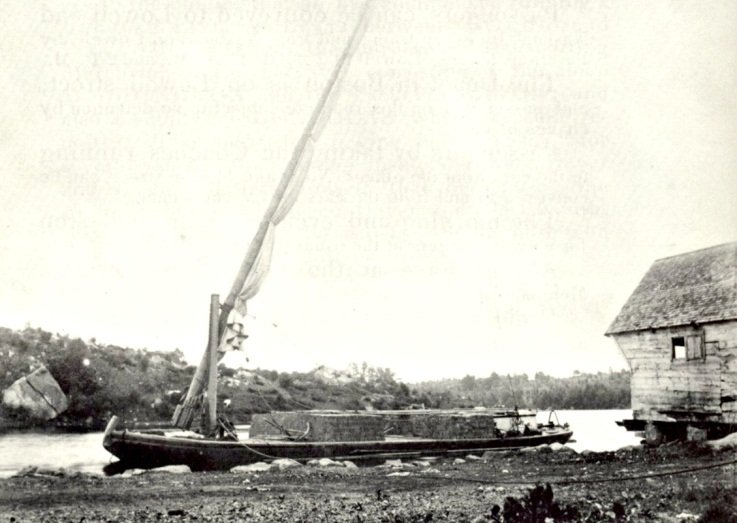

During the 17th century, ships coming into Dover from foreign ports had little difficulty as the settlement’s commercial center was at Dover Neck where the rivers were wide and channels deep. As the town moved northward to its present site, a landing was established below the falls of the Cocheco. About 1785, the inland settlement at Cocheco (now downtown Dover) became the population and business center of Dover. Importing goods to the Landing’s piers became a more complicated operation. Most commercial shipping occurred on the Cocheco as the Back/Bellamy River was too shallow and too crooked for most sizeable vessels. Even so, the Cocheco was difficult to navigate for the larger ships except at high tide. It was during this period that the gundalows evolved. Each gundalow could carry over thirty tons of cargo and could dock at Dover Landing at half-tide.

Much of Dover’s early commercial shipping success is due in large part to the flat bottomed gundalow, a watercraft indigenous to the Piscataqua region. Named after the Venetian gondolas, it was designed to carry freight and passengers, navigating the shallow rivers and dangerous currents. At first, they were square-ended, undecked, and had no permanent or attached rudder. During the early part of the nineteenth century, a rudder and tiller were adopted and in some cases, small square sails and removable masts. Later, the spoon-bow and round stern appeared, as did a short, stubby mast rigged with a lateen sail. With a crew of two or three men, these large gundalows made good speed on the river. The operators were described as a special breed of boatsmen.

By 1800, over a dozen brickyards were prospering along Dover’s waterfronts, firing their kilns with 30,000 tons of cordwood delivered annually by the gundalows. Brick making in Dover began very early in the settlement at Dover Point and Dover Neck brickyards. It became a very large and profitable business. The gundalows went down the coast to Boston and Cape Cod carrying bricks and granite, returning next week with a load of bog hay or meadow grass. Much of Boston’s finest architecture was constructed with Dover brick.

Gage’s Brick Yard

Small packets (keel boats 30-40 feet in length) sailed regularly into Portsmouth, Portland, and Boston, carrying light freight and passengers. By 1825, with the formation of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company’s gigantic mills surrounding the downtown falls, Dover was the second largest town in New Hampshire, behind Portsmouth. Local shipyards built at least half a dozen vessels each year ranging from 30 to 600 tons.

In 1835, after hearing rumors that the railroad was coming to Dover, a group of packet captains, previously in competition with each other, formed the Despatch Line of Packets, a fleet of seven vessels promising regular routes to other east coast cities. By 1840, nearly 200 ships came into the port of Dover (many having to be “lightered” by the gundalows) and the value of goods shipped just between Dover and Portsmouth was $2.4 million.

In 1877, the Dover Navigation Company began operations. Owners of the 10-schooner fleet were a group of ambitious Dover businessmen who made a profitable investment in shipping coal and finished cotton to and from ports around the world. In 1888, Dover’s citizens admired the “J. Frank Seavey” at the Landing: 144 ft long, 34 ft wide, and carrying 600 tons of coal for the mills. In fact, because the Cocheco River had been dredged and widened, during the last decade of the nineteenth century, it was common to see eight or nine schooners in port at one time.

However, commercial shipping traffic to downtown Dover ended abruptly on Dover’s Black Day: March 1, 1896. A late winter storm ravaged the city, destroyed bridges, and caused a ten foot rise in river levels. The storm deposited back into the Cocheco River all the sand, silt and debris that had been dredged out over the previous sixty years. Then Landing never recovered from the devastating blow.

Bracewell Block after the flood

Roads and Streets

Early Paths

The story of road building in Dover closely parallels that of the nation. The first paths were those formed by the abundant wildlife that inhabited the region, as they roamed the wilderness for food and shelter. These animal paths became hunting and fishing trails as they were followed by the Natives on their quest for fish and game. The first European settlers at Dover Point made a path from the Point to the landing cove on Little Bay, along which they hauled their catches of salmon. As settlements increased and movement extended northward, paths followed Indian trails. Other paths were cut by hand through the wilderness.

For the first century after Dover’s settlement, roads developed over the course of time, with new roads reflecting the needs of the town. Indian paths continued to be used and were widened only intermittently. Lanes were created from the main road to the waterfront and highways evolved as a means of travel from the center of town to its peripheral mills. A cart path evolved between the two settlements of Dover Point and Cocheco and crossed private lands, including Tuttle’s Farm. The traveler encountered gates at each farm which he was required to open and properly close when passing through. These early roads connected settlements and farms, often meandering along the courses of streams, sometimes pushing their way over hill and valley. Many of these paths have since disappeared, but others evolved into trading routes which form the basis of many of today’s streets and highways.

Dover Neck

Mast Roads

In the early days of British exploration of our area of New England, their primary interest was to obtain masts for the Royal Navy. They found a rich resource in the tall, stately pines growing in abundance in our forests, and paths were cut through the north country from the Seacoast of New Hampshire.

The stories of bringing the masts down and transporting them to the sea are fascinating and one that demonstrates the ingenuity of our ancestors. Dover pines were much desired, some exceeding the 40” diameter required for main masts. Some were as long as 120 feet long, each ship demanding 23 masts total. The logs were hauled out of the forests on chains slung under axles of wheels eighteen feet high. There are records that some teams of oxen numbered up to 120, with some being used behind the wheels to slow down the ascent of these huge logs as they maneuvered through the mountains in their trek to Portsmouth. In 1634 the first shipment of masts was sent to England.

Many paths were used temporarily and eventually grew back, others over time were widened and were used for general travel as well. In some cases, such as in the Durham and Madbury areas, farms and towns developed as the paths became thoroughfares to the shipping ports of the rivers and ocean. In 1667 there was a “masting path” which followed along what is now Somersworth Road turning toward Madbury. One from Wingate’s Slip, mentioned in 1682 when John Knight bought land of Richard Waldron on the west side of Bellman’s Bank River, is now Mast Road. This ran, as now, along the north side of Drew’s Hill toward Madbury, perhaps joining the other. Wingate’s Slip was named for Wingate of Dover Neck and was later known as Ford’s Landing. In 1729 the town built a road over the Mast Path from Wingate’s Slip to Madbury. Mast Road is still an important connecting road between the two communities.

Turnpikes

At the end of the 18th century, the best roads were the private turnpikes. For a period of about 30 years prior to the American Revolution, by order of the Royal Governor and General Court, a number of roads were laid out to be built by towns and settlements for the purpose of establishing lines of travel between communities that were not connected. Because of difficulties in raising funds, few of these “Province Roads” were actually completed. The excessive cost of the Revolutionary War curtailed all but the barest necessities and governmental road building virtually stopped. In its absence, Turnpike Companies mushroomed throughout the fledgling nation, and in 1794, reached New Hampshire.

Although the area is now in Durham, at the time of its connection, the first New Hampshire Turnpike terminated in Dover. In 1794, the Turnpike was chartered from Concord to the Piscataqua Bridge, roughly following the line of what is today US Route 4. The word “turnpike” refers to a hinged bar that was positioned across the road to facilitate toll taking. The state’s early turnpikes were mostly private toll roads built mainly for profit rather than service. Profits quickly diminished and by the mid 19th century, the toll roads became free roads. Due to a lack of maintenance, many of them became abandoned. Some of these roads, or parts of them, are now incorporated into the State Highway System.

Until 1879, state roads were maintained by the localities. Each town had a “Road Surveyor” who was responsible for the care of the local section of the highway. Most towns could not afford the cost of road maintenance and improvements, so travel between towns became increasingly difficult. In 1879, the Legislature began a modest program of construction and repair of certain roads, marking the entrance of the state into what is now its scientific program of road building, which is also its biggest business.

Stagecoaches

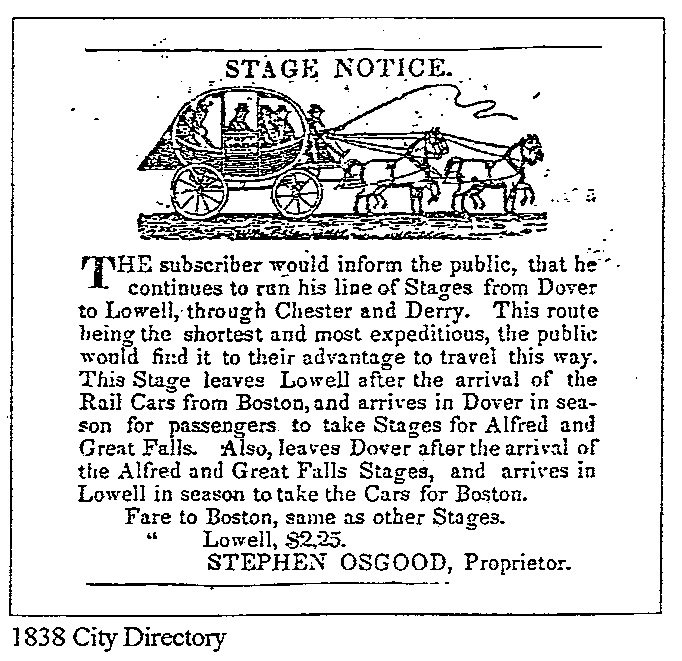

The state developed, and communities and towns expanded as farming, lumbering and mills along the rivers provided trade opportunities in other areas. The network of roads that connected one place to another and in the 1800’s spurred the development of the stagecoach as a popular mode of transportation for travelers. New Hampshire even produced its own design, called the Concord Coach which became well known nationally.

The Concord Coach was manufactured by Concord’s Abbot-Downing Company. Its claim to fame was its unique suspension system which utilized leather straps instead of the traditional metal system. The effect was a more pleasant rocking motion rather than a jarring bounce, making travel along the nineteenth century roads more comfortable. Mark Twain praised it highly.

One of the stagecoach drivers was Henry Sayward who lived at 157 Central Avenue, a Federal style three story building (c.1860). Sayward later became the first conductor on the Dover and Winnepesaukee Railroad and eventually a partner in the Niles and Company Boston Express which ran daily cars to Boston from the B&M railroad depot on Third Street. Sayward sold the house in 1900.

Henry Sayward

Traveler’s Inns

On their route between Concord and Boston, stagecoaches used to travel on what is now Silver Street, where a number of taverns operated to provide travelers with food, drink, and rest. The oldest building in Dover still occupied is at 17 Silver Street. It was a built as an inn in 1708 by Col. James Calef when Silver Street was called Barrington Road and was only a cart track. Daniel Webster stopped there when he was a young lawyer and argued a case at the court house. Across from Calef’s Inn was a tavern operated by Christine Otis Baker in the early 18th century. The tavern was later Kennedy’s saloon which was known for its canopy over the sidewalk and hitching posts along the curb. This brick building burned in the 1970’s. At the corner of Silver and Rutland Streets (114 Silver St.) is a building which served as a tavern operated by N. Watson, who also farmed the land (c 1780) and later was a tavern/hostelry run by a Mr. Bickford.

As early as 1604, George Walton kept an “ordinary” at the intersection of High Street and Fore River Lane at Dover Point. No more is know of this inn than its presence on a map of the era.

At the intersection of Back River Road and Durham Road is a colonial house, well over 200 years old. In 1780, it was operated as a tavern which was bought by Captain Samuel Dunn in 1820. Adjacent to Dunn’s Tavern, a favorite stop for travelers, was a reputedly haunted area known as Dunn’s Woods. These dark, damp, lonely woods were enclosed by hills and were remote from any dwelling. It was said to be the scene of many a robbery by day and supernatural occurrence by night. The ghost stories originated from the phosphorescent lights which on dark nights were often seen to gleam among the bogs and decayed wood, startling the belated and weary traveler.

On Goat Island, was the “Pistataqaue-bridge Tavern”. The halfway point of the Piscataqua Bridge, the tavern was built before Oct. 24, 1791, on which day the agents of the Bridge company advertised it “to be let”, describing it as of a “new, commodious, double house, with a large, convenient stable, and a well that afforded an ample supply of water in the driest season.” This tavern was burned down many years ago, and no buildings now remain on the island.

The Railroad

Beginning as early as 1830, trains had started rumbling through America’s countryside. At first it was hard to predict their impact, but not for long. Spurred by huge grants of public land, railroad companies cut a path through the continent. Starting in the heart of the large Eastern cities, the rails pushed out along the suburbs they both served and created, into farmland and the mountain wilderness beyond. It took only eleven years for this new technology to come to the city of Dover.

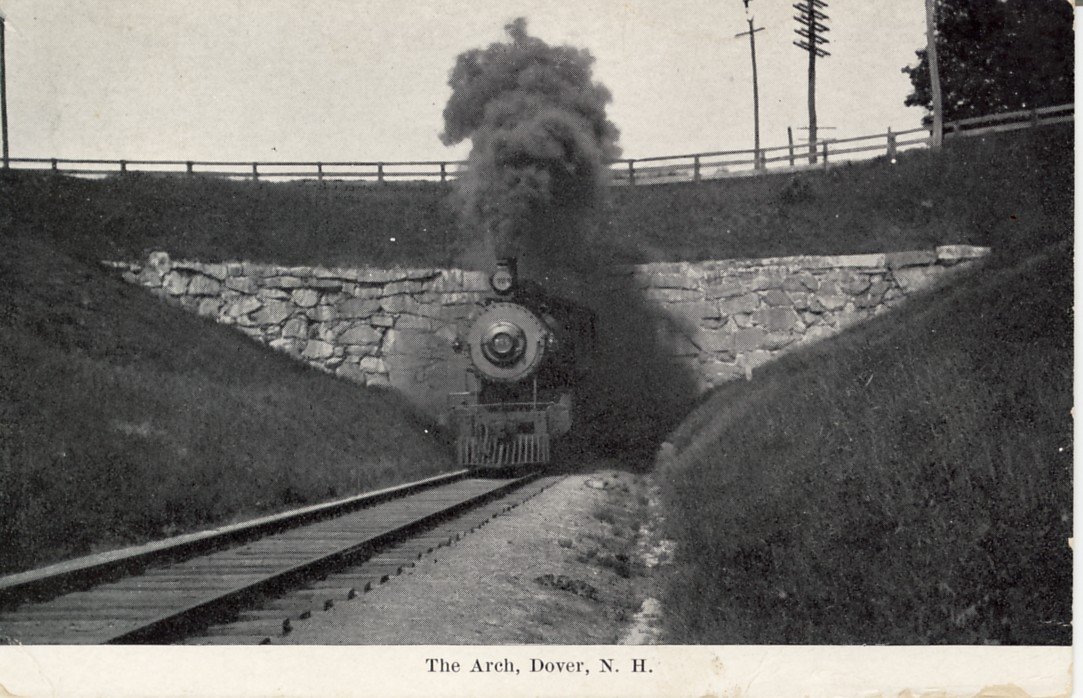

In 1838, after the New Hampshire granted the Boston and Main Railroad permission to cross into the state from Haverhill, Dover voters assented to the tracks passing through their town. The Dover Gazette lobbied against it, stating that the railroad would put men out of work who rode the stages and coasting vessels. Dover would “be turned into a town of idlers, under a tyrant’s power.” When the first B&M locomotive steamed into “Coffin’s Cut” on September 1, 1841, great crowds assembled on Arch Street. Most had never seen a train before and one man was heard to remark, “You can’t fool me! I know there’s a horse in there somewhere.”

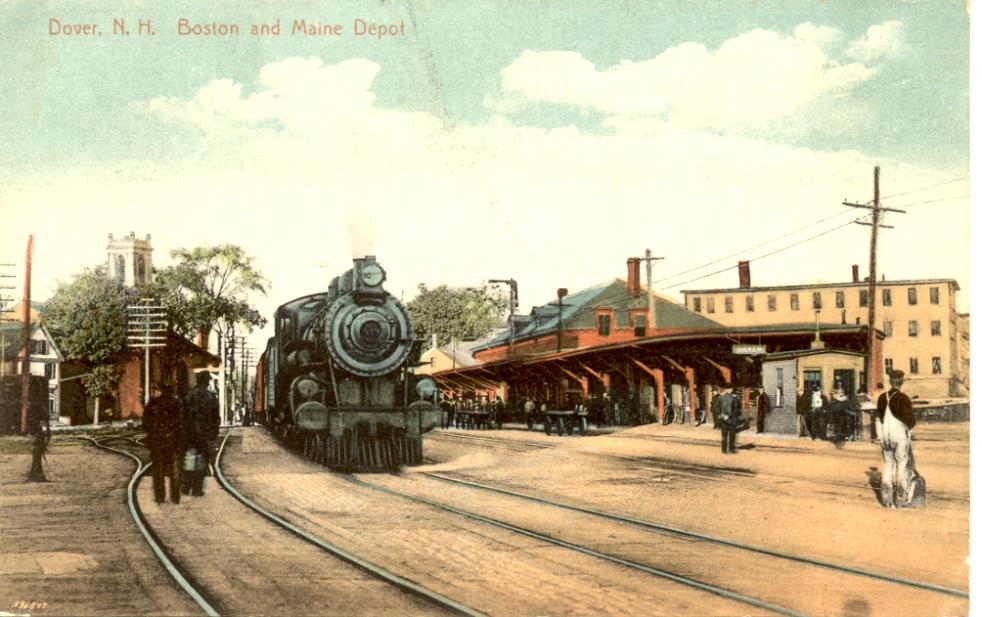

In 1842, a year after the tracks from Boston reached Dover and the Boston and Maine Railroad began carrying passengers to the city, the Third Street Station was built. Soon the railroad added a roundhouse and engine facilities near the Cocheco River. In the days of steam, Dover being midway from Boston to Portland, many trains stopped here to take on water at the Chestnut Street tower. In 1851, the Cocheco Railroad to Alton was completed. In 1874, the Portsmouth and Dover Railroad was formally opened for travel. There were nine railroad stations serving the community: Dover, Cocheco, Folsom Street, Sawyers, Cemetery, Cushing’s, Bellamy, Hilton, and Dover Point.

Quite opposite of the Dover Gazette’s prophesy, the railroad gave a boost to Dover’s industries and employment outlook. The nine stations within Dover’s boundaries moved the focus of business from the Landing to Third Street. The development of Third Street and Upper Square was largely shaped by the railroad, replete with businesses that depended on the railroad for clientele. Hotels, theaters, saloons, and restaurants lined the south side of Third Street for years. At the turn of the century, Upper Square was a bustle of activity when the steam railroad, electric railway, horse and carriage, and automobile served the transportation needs of the city and surrounding communities.

It was not uncommon for fifty or more trains a day to originate in or pass through Dover, with trains to and from Boston, Portland, Portsmouth, Conway, and others. In the winter, ski trains often put on a second locomotive for the run up the Conway Branch. In 1919, a new roundhouse was built further east near Oak Street. In 1928, Dover became headquarters for the Portland division of the B&M and the two-story station was modified to three.

In April 1935, B&M’s new streamlined “Flying Yankee” was brought into service in Dover. For twenty-two years, this train ran between Boston, Portland, and Bangor, carrying twice its normal capacity during the Second World War. It was also used to take scenic excursions to the White Mountains and to White River Junction, Vermont. It served exclusively as a passenger train for almost three million miles, until it was replaced by the Budd diesel rail cars (known in Dover as Buddliners).

The steam train was permanently retired from Dover’s tracks in 1952, replaced by diesels, and the Chestnut Street water tower has since been demolished. The last passenger train left the city on June 30, 1967. Today, without passenger service, only a few through freight trains pass by. The Division Headquarters left Dover and the larger station was demolished. The site now serves the automobile as a parking lot. In the 1960’s, there was a new “modern style” passenger station built in the Second Street yards, but now is not used as a station, and is architecturally dated. Currently, there are plans of reviving passenger service from Boston to Portland, and Dover is expected to be one of the stops on the route.

The Horse Railway

The Horse Railway evolved as a local enterprise, serving Dover residents for twenty years, starting in July 1882. The road was over two miles long and the initial trip was between City Hall, Sawyer Mills, and Garrison Hill. The car was generally equipped with two horses, with a third added if the car was full. Each car in the horse railway could carry 26-30 passengers, riding along 100 tons of wrought iron rail. Trolleys ran every thirty minutes and over 5000 tickets were sold each week.

The Dover Horse Railway Company was organized by Harrison Haley, proprietor of the Garrison Hill observatory. Later, he sold his shares to Mrs. Mary Dow, who became the first woman president of a railway company. Noted as a remarkable woman, according to the New York Sun, she “was able to reduce fares from six cents to five, raise all her employees’ pay, double her insurance coverage, introduce a ticket system that cost her nothing because she solicited advertising for the banks on the stubs, supervise the purchase and care of all the horses, and still realize a hefty profit for the investors.”

Harrison Haley

The short history of horse drawn trolleys in Dover came to an end soon after Mrs. Dow sold the railway to Henry W. Burgett of Massachusetts in 1889, who converted it to an electric railway.

Electric Railways

Dover’s connection with electric railways preceded construction by about forty years. In 1847, Eliot inventor Moses Gerrish Farmer, whom many consider an equal to Thomas Edison, demonstrated his newest apparatus at the Dover Town Hall. His simple Electro-Magnetic Engine, with a few feet of track and a car seating two, was destined to grow into the subway and trolley systems of his future and are the basis for the magnetically levitated high speed trains of our present and future.

Mr. Burgett extended the route six miles up to Willand Pond (at the Dover/Somersworth city line) to access an amusement park he was developing. Soon after the sale he electrified the new portion of the track, using electrified overhead wires to propel the cars. Dover was the first city in the state to have an electric railway. Its maiden voyage was on August 18, 1890.

Burgett also built a power plant for the railway cars at his new park at Willand Pond in Somersworth. At this plant 13,200 volts of A.C. Power from Portsmouth was converted to 600 volts of D.C. power. Under the name of Union Street Railway, Burgett modernized the system with 60 foot steel rails. Two years later the stretch from Franklin Square to Sawyer’s Bridge was also electrified.

Dover and Portsmouth Street Railway

The fleet consisted of seven closed cars and eleven open ones, and three snowplows. During the summer the cars were open and the benches faced forward. In the winter months, the seats were changed to run along the walls of the car with a center aisle for the conductor. As there were no other vehicles on the road in the winter months, the trolleys plowed their own tracks, leaving huge piles of snow along the sides of the street.

After several years and changes in management and a merger with the Rochester Railway, by 1901 the railway focused on providing convenient schedules for passengers going to and from Dover, Rochester, and Somersworth. It ran hourly in the winter, spring and fall, half hourly in the summer and every fifteen minutes in July and August after 1:00 P.M. This continued until the automobile made its debut providing more efficient, cheaper, and faster transportation. The Dover, Rochester, and Somersworth Railway made its last electric trolley run on September 15, 1926. Bus service was eventually substituted between the three cities and the rails were dismantled in 1927.

Bridges

Piscataqua Bridge

The first bridge at this site was the Piscataqua Bridge. Built in 1794, the bridge connecting Dover and Newington was an engineering masterpiece in its time. The bridge consisted of three sections, stretching 2362 feet over water as much as 50’ deep, and was for many years, the only overland route to the seacoast. The first section was a horizontal section built on pilings from Fox Point in Newington to tiny Rock Island. The second section was an arch from Rock Island to Goat Island, high enough for gundalows to pass beneath. The third section, from Goat Island to Cedar Point (also known as Meader’s Neck), was on pilings similar to the first section. The bridge opened in November 1794 with a toll at the Dover end. For the benefit of weary travelers, a tavern was operated on Goat Island. Ice caused extensive damage to the bridge pilings, as major repairs were performed three times during its life. Ice caused its ultimate destruction in 1855, the same year that Dover became a chartered City. Since railroads were in use by then, the remains of the bridge were abandoned.

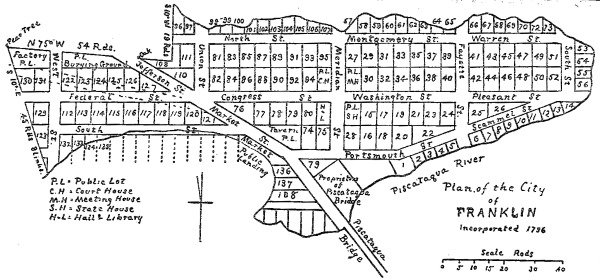

Cedar Point was once the site of an ambitious project of building a city to take advantage of the Piscataqua Bridge. The Bridge made the seacoast accessible without resorting to travel by ferry. In 1796, two years after the bridge was built, the surrounding land was incorporated as Franklin City. A plan marked out streets and lots. Despite early enthusiasm, a prosperous village never materialized as a decline of shipping during the War of 1812 led to the city’s demise. Some lots were sold and one house was built. Some boats were built at the boatyard, but after a few years, Franklin City faded into history. Most of the property is now in the towns of Durham and Madbury.

Scammell Bridge

The Scammell Bridge was built in the 1930s. It is a unique bridge for its time because of the center drawbridge. This was built because a fisherman who lived upstream of the bridge gave the money to the state to construct the drawbridge so that he could reach the bay, and ultimately the ocean, by boat from his home. On the opposite side of the road, we can see an historic marker, describing the bridge. By the end of the century, the marker will be the only reminder of the bridge. The Scammell Bridge is slated for demolition within the next few years as part of an upgrade to Route 4 and Boston Harbor Road.

The Automobile

In 1856, Walt Whitman’s “Song of the Open Road” expressed the sentiments of freedom and opportunity that existed along the “long brown path” of his time. Fifty years later, that path was on its way to becoming a long grey ribbon. The river, the rails, and the horses all had a new competitor, destined to make them all obsolete. The automobile changed the life and culture of Americans as no other invention had, a transformation of both the city and the countryside through which the newly liberated Americans would speed.

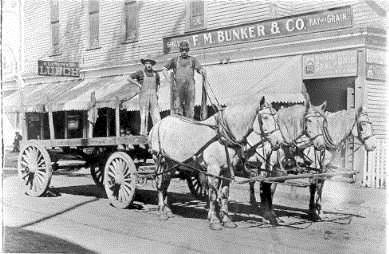

At the turn of this century, Dover began to see the impact of the automobile. Auto dealers, garages, gas stations, and parking lots replaced barns, liveries, blacksmiths, and harness shops. The city directory of 1884 had a wealth of advertisements for carriage drivers, teamsters, horseshoeing, carriage repair, sleighs, job wagons and buggies. In 1909, twenty five years later, advertisements promoted Reos, automobile stations, tires, automobile repair, oil, and gasoline. By 1934, the most prominent displays in the directory were large ads for Fords, Dodges, Plymouths, Exide batteries, Simonizing, Trico wipers, and Carter carburetors. Randlett’s Carriages, renowned at the end of the nineteenth century, is now the site of a gas station at the corner of Central Ave. and Silver St.

Bicycle shop owner Frank Wentworth, who lived on Tuttle Square at 202 Central Avenue, brought the first automobile to Dover. By 1909, he was selling Reos, Premiers, and Overlands out of his “Automobile Station” at 264 Central Ave. Up the street from Wentworth, at 185-187 Central Avenue, lived bartender Patrick McManus who was best know for his flashy Stanley Steamer automobile. By the 1930s, auto horsepower had replaced the horse as city transportation. Horseback riding as a sport emerged, and riding schools catered to the “horsey set”. McManus’s carriage house served as the Dover Riding School, where saddle horses were boarded, rented, and schooled.

In 1906, Fourth Street resident Michael Kidney, son of Dover’s first auto mechanics, built a two cylinder car in his garage. When it was complete, it would not fit through the door and had to be dissembled to move it outside. Around 1948, Kidney’s son moved the house (by horse power) to the end of the street in order to expand the garage. Today the garage is used for storage by Robbin’s Auto Parts.

Car dealers sold their wares out of Washington Street storefronts, much in the same manner that other goods had been sold by retail businessmen for years. It wasn’t until population shifted to the suburbs that the car dealership that we now know came into existence. Robbins’ Auto Parts retail store is located on Washington Street, in a building that at one time was a Pontiac dealership.

By the 1950’s, outlying development created by the automobile required new and upgraded thoroughfares to accommodate the car, and, in 1956, the Spaulding Turnpike was constructed over the old Portsmouth & Dover Railroad. The Spaulding allowed swift movement from Dover to almost any destination in the country. It also allowed motorists to speed by Dover without the encumbrances of city streets. With an automobile, people could live, work, and shop elsewhere, no longer bound by walking distances or train schedules.

Afterword – Where are We Going and How do We Get There?

The river had not been used since Dover’s Black Day in 1896. Horse & carriage traffic is long gone. The last trolley left Dover in 1926 and last passenger train in 1967. Urban Renewal in the 1970’s would further cut into city’s fabric as entire blocks were demolished for new housing. By the 1980’s, the commercial center of the city had moved northward again, out of downtown to the “Miracle Mile”, where fast food and superstores allow the resident convenient shopping and acres of parking. But history repeats…

Recently, interest in the waterfront has been rekindled, and there has been discussion of reviving passenger train service from Boston to Portland, with Dover as one of the regular stops. A redevelopment of the downtown has been slowly taking shape with a focus on a pedestrian-friendly streetscape. The state had developed a proposed network of intercity bicycle routes, and the city will be upgrading Dover Point Road and Durham Road for bike traffic within the next few years.

All of this points to a rediscovery of the importance of integrated transportation rather than sole dependence on the automobile. The story of our rivers, rails, and roads is a tale without end. As we approach the next chapter of this story, we must look back at our history. It is in our history that we will find the ideas, the images, and the inspiration needed to succeed in building a transportation system for the next century, for the future of Dover.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.