Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

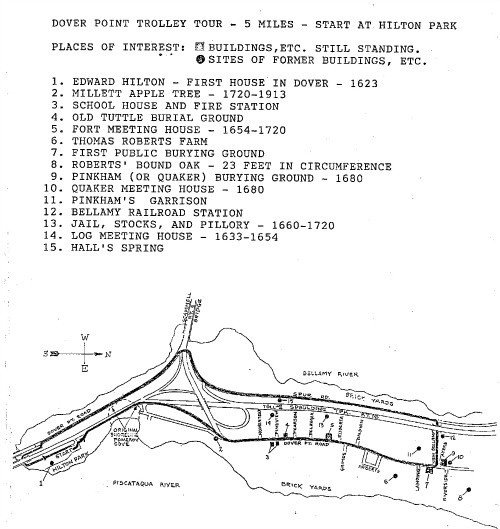

1998 Heritage Trolley Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet October 1998 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 1998.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

Heritage Trolley Tour

Dover, NH

Oct. 1998

Introduction

The year 1998 marks the 375th anniversary of the settlement of Dover Point and the 20th annual Dover Heritage Tour. As the City of Dover and the Northam Colonists Historical Society celebrate these milestones, it is only appropriate that the 1998 Heritage Tour focus on the people, places, and events surrounding the settlements of the fishing and farming communities of Dover Point and Dover Neck.

The Cocheco River and Piscataqua Basin were home to aboriginal people 3,000 to 5,000 years ago. Ancestors of these people migrated northward, in pursuit of big game such as mastodons and mammoths, about 10,000 years ago, with the shrinking of the glaciers. Many set up nomadic camp sites by river falls, where fishing was good and, where, in later periods, they could portage their dugout canoes. The descendents of these nomads were the people of the Algonquins, including the local Cochecho and Piscataqua tribes.

At the time of the arrival of the Europeans, the local peoples had well developed fishing and farming traditions. The early people had been attracted to the Piscataqua and Cochecho because of the plentiful salmon, shad, alewives, and lamprey, which they fished with weirs, basket traps, spears and bone, and stone hooks. Alewives are small pond-fish; shad are larger, and keep to the larger streams and lakes for spawning. Salmon prefer the cold, swift water fed by springs. At the beginning of the fishing season, the native men built an ahquedakee, or weir, which was constructed by placing a line of sapling stakes across the river, driven into the mud some ten or twelve feet apart. Birch tops or brushwood was interwoven among the stakes, stretched from stake to stake to make a barrier to the fish; to one side a space was left to let some fish to pass. Fish caught by the weir would be collected daily and prepared for storage. The squaws dressed, split and laid the catch in the sun to dry, or hung the fish in the wigwam to smoke. The natives also speared fish by torchlight, and in the winter season fished through the ice with stone hooks. The seacoast Indians also took fish in a manner still pursued on the coast of Maine and Nova Scotia.

In addition to plentiful fishing grounds, the natives near the Piscataqua and Cochecho Rivers valued the outcrops of quartz and felsite along its banks. The hunters and gatherers quarried these rocks for use in tool making. Archeological sites along the river have unearthed many Native American artifacts. Most of the artifacts uncovered are waste matter that accumulated from the making of tools, and broken fragments of pounding implements or axes.

The typical crops of the Pennacooks were corn, beans, melons, squashes, pumpkins, and gourds. They also gathered acorns, walnuts and chestnuts, and dug for groundnuts. The seacoast land was heavily forested, so farmland was cleared by girdling and burning. Tilling of the soil was done by using only an axed or hoe. The axe was their main instrument in agriculture, as well as in other business, and was in use all through the tribes of northern North America. The common axe had a sapling for a handle, pliant so as to bend around the axe, and tied with the roots of spruce or the sinews of animals. They sometimes formed their hatchet handle by a more slow but surer process: they selected a small, straight hickory, oak or other tough sapling of the proper size, and splitting is as it stood, forced the stone axe through the cleft. They left it there until the sapling, in its growth, had enclosed the axed firmly within its wood. The sapling was then cut at the proper length, and the handle shaped to the taste of the owner. Their hoes were generally made of clam shells, or sometimes granite, fastened to stiff handles.

They planted in rows, much the same as we do at present. Fish was used as a fertilizer, with a shad or alewife buried in each hill of corn or vegetables. The fish were so plentiful that the wives of the first settlers shoveled them out of the brooks with fire slices and “shod shovels,” while their husbands were preparing the fields. This technique, as well as the advice to begin planting “when the oak leaf became as large as a mouse’s ear,” were among the skills passed on to the first settlers.

Much of the success of the European survival in New England is due to the Native American skills. Thousands of years of experience had taught the Cochecho and Piscataqua tribes how to plant and process maize, to collect medicinal herbs, to track, trap, fish, clear land, build canoes, make snowshoes, and navigate rivers. Indian leader Passaconnaway presided over nearly a half century of relative peace with encroaching European settlers. His descendents were less forgiving of the double-dealing Europeans that used trickery, guns, whiskey and disease to effectively wipe out the native population. A rash of organized native reprisals struck nearly every Seacoast town around the turn of the 18th century. By the middle of the 1700s, the American Indian was all but extinct in New Hampshire.

Indian Customs

To prevent the crows (which the Indians called “Kaukort,” from the sound of caw or screech) from devouring the young corn, small lodges were built in the fields, in which the elder children watched. They did not kill these crows, as they held them as sacred as their greatest benefactors. They had a belief that a crow brought their first kernel of corn and a bean from the country of the south west, a present from their Great Mamit, “Kaurautonwit’s” field, in the southwest. From this kernel of corn and from this bean, they supposedly derived all their corn and beans. Hence, they thought the crow entitled to a share, and did not offer a bounty on his head, even though he might at times take more than was fairly his share.

Their corn was of various sorts and colors, and was cured in various ways. Much of it was used when green, either boiled or roasted for immediate use; and still another portion was gathered when in the milk and dried in the sun upon mats, for fall and winter use. The corn thus prepared was called sweet corn, and when boiled or soaked, and roasted, had much the same taste as green corn. The ripe corn was gathered into heaps, and dried thoroughly, and put by for parching and grinding. They generally parched their corn before grinding or pounding, as they usually pounded their corn with pestles in wooden mortars. Their pestles were usually of granite, but often of other stone. They were often elaborately finished, and sometimes upon the top of them there was an attempt at rude sculpture. Dover Historian Dr. Jeremy Belknap speaks of one upon which was sculptured the head of a serpent. Their mortars were often formed of stone, but were more recently former out of the transverse section of a log, and often these were made in the top of a stump.

They had gourds of various kinds. They cultivated the water melon and the Pompion or Pumpkin. The water melon was used in fevers. The squash and pumpkin were cooked by boiling or steaming and often eaten raw. The common gourd was cultivated for use and pleasure in the form of dippers and musical instruments. Other specimens of the gourd were cultivated for their edible properties, and were designated by their general name of Askietasquash.

For more than a century after Columbus discovered America, the Piscataqua was unvisited and virtually unknown to European explorers. The first exploration of its shores, of which there is any record, was that of Martin Pring. In 1603, twenty-three year old Pring fitted out his fifty ton ship Speedwell with thirty men, and William Brown’s twenty-six ton bark Discoverer with thirteen men. This small fleet was fitted out under the patronage of the mayor, aldermen, and merchants of the wealthy English city of Bristol. They first touched at some of the islands near the entrance of Penobscot Bay, and then visited the mouths of the Saco, Kennebunk, and York rivers, which Pring says they found “to pierce not far into the land.” They next proceeded to the Piscataqua, which Pring called the westernmost and best river, and he explored it ten or twelve miles in the interior. Capt. Pring, who, wrote of “goodly groves and woods and sundry sorts of beasts, Stags, Deere, Beares, Wolves, Foxes, Lusornes and Dogges with sharp noses.” Pring also reported signs of Indians living in the Piscataqua area, noting with special interest and admiration their birchbark canoes.

The next visitor was one whose adventures form an important chapter in English as well as American history. It was in 1614, that Captain John Smith, of Pocahontas legend, arrived on the coast of Maine with two vessels, and while his men were engaged in fishing, he with eight of his company in one of his boats, ranged the coast from Penobscot Bay to Cape Cod. Captain Smith wrote back to his countrymen “Here should be no landlords to rack us with high rents, or extorted fines to consume us. Here every man may be a master of his own labor and land in a short time. The sea there is the strangest pond I ever saw. What sport doth yield a more pleasant content and less hurt or charge than angling with a hook, and crossing the sweet air from isle to isle over the silent streams of a calm sea?”

The settlement of New Hampshire did not happen because those who came here were persecuted out of England. The occasion, which is one of the great events in the annals of the English people, was one planned with much care and earnestness by the English crown and the English parliament. In New Hampshire, King James the First began a colonization project which not only provided ships and provisions, but free land bestowed with one important condition, that it remain always subject to English sovereignty. So it remained until the “War of the Revolution.”

John Smith drew the first map of our coast, calling it “North Virginia” but King James later revised this into “New England”. On his map, Smith gave the locality of Portsmouth the name of Hull; to Kittery and York he gave the name Boston. Smith was also the discoverer of the Isles of Shoals, which so pleased him that he gave them the name of Smith’s Isles. As a result of Smith’s report, new interest in this northern territory was awakened. The Pilgrims established their colony at Plymouth Massachusetts in 1620.

John Mason was a London merchant and ex-Governor of Newfoundland. At different times, Mason shared ownership of several sections of New England, finally centering his attention to the area lying south and west of the Piscataqua River. The name Portsmouth was added to John Smith’s map, taken from the English town where Captain John Mason was commander of the fort, and the name New Hampshire is that of Mason’s own English county of Hampshire.

It was under the authority of a grant from the Plymouth Council that settlements at Portsmouth and Dover were commenced. In 1622, the Council selected David Thomson to start New Hampshire’s first settlement. Thompson, a big blue-eyed Scotsman was well educated and had personal knowledge of the New World. The Council granted Thompson consisting of “six thousand acres of land and an Island in New England”. In the spring of 1623, Thomson, aboard the ship Jonathan, was sent from England with all the necessaries to begin a settlement. Thomson established himself at Pannaway, or Little Harbor, near Portsmouth, where he remained for four years.

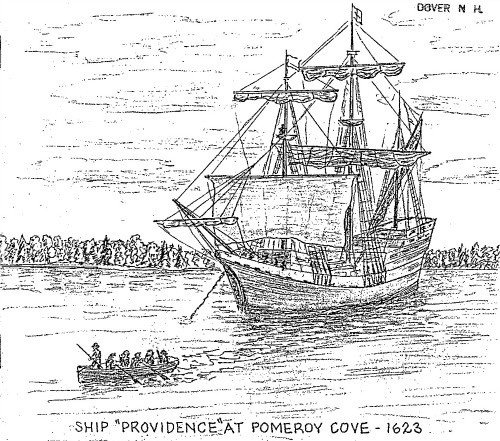

The first European settlers of Dover were the brothers Edward and William Hilton, and Thomas Roberts. Arriving soon after David Thomson, the Hiltons settled at Dover Point, a part of Thomson’s grant, where they farmed, fished, and traded with the natives. The Hiltons, who had been fishmongers in London, arrived at Pomeroy’s Cove in the ship “Providence” of Plymouth.

While Thomson remained in Portsmouth for four years, he then removed to Boston. Hilton remained permanently at Dover Point, and the settlement there has been continuous to the present day, making Dover the oldest continuous settlement in the state. The Hiltons gained a legal patent for their settlement, but when they realized the powerful Massachusetts Bay Colony might claim the whole Piscataqua region, they sold the patent to a group of English Puritans who might find the rule of the Bay Colony more tolerable than they would. Captain Thomas Wiggin, who was the first “Governor” at Cochecho, and had a power of granting land to settlers, led this group. As trade was the settler’s principal objective, they took up small lots, intending to build a compact town at Dover Neck.

On the most inviting part of the landscape, they constructed their first log meeting house which was surrounded with an “entrenchment and flankarts.” Then, having cleared the trees, the first houses were built in this section. The First, or “Log Meeting House,” built on what was to become Low Street, was the center of business during the first years, as all public meetings were held there, both religious and town meetings. The village quickly grew such that after a few years, the first meetinghouse became too small. Since, the population was shifting northward, in 1654, the second, or “Fort Meeting House,” was built at Nutter’s Hill, on what was then High Street. Richard Waldron built the house in exchange for timber rights. The town meetings were held there until 1720, when the bell was removed and the town meetings were held at the new meeting house on Pine Hill, again following the population shift toward the north.

The earth outline of the second meetinghouse fortification is still visible today. In 1667, it was ordered by the Town Selectmen to build a fort around the meetinghouse. It is not explained why the meetinghouse was fortified. Thirty years earlier, Tahanto, a sagamore of the Penacooks, was said to have given the Hiltons corn fields along the river. Lather, the so-called Wheelwright deed, signed by Passaconaway, further gave the colonists sway over the land from the Piscataqua River to the Merrimack and to a point 12 miles up the Cochecho River. During its first fifty years, under the benign influence of Passaconaway, the leader of the loose confederacy of Penacook tribes, Dover was never at any time troubled, even during the fiercest of Indian Wars. The year 1667 was a time of profound peace.

The great enemies of the Natives were not the white Europeans, but the warlike Mohawks who were pressing east across the Connecticut River valley from their homelands in the Hudson River Valley. The white settlers at first were few in number, and the Pennacooks and other New Hampshire tribes saw trade as a way to strengthen themselves against the Mohawks. However, trade made the Natives dependent on European goods, disrupted their social order, and ultimately strengthened the Mohawks more than themselves. By 1640, in New England the white population outnumbered the Algonquin, and the native population began to feel the disadvantages of settlement. It is doubtful that the Indians, who had little conception of private ownership of land, realized that they were signing away their hunting and fishing grounds forever.

Begin Tour at HILTON MONUMENT, HILTON PARK

The monument at Hilton Park commemorates Edward Hilton and the 1623 Landing.

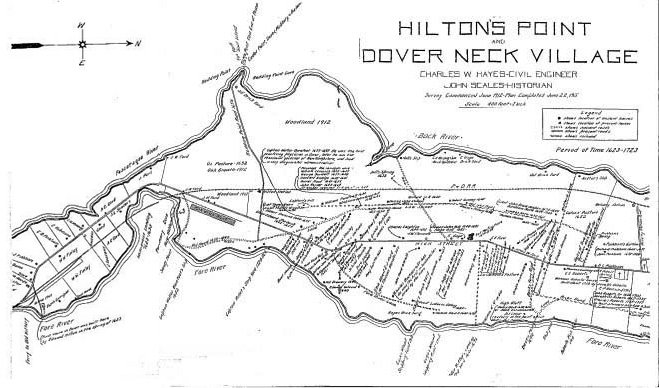

Dover Point is the name now given to Hilton’s Point, where the first landing party settled in 1623. The first immigrants lived close to the original settlement at Dover Point, and were engaged in fishing, the original purpose of the settlement. Both banks of the settlement were lined with numerous ships, landings, and shipyards. Not only were there small shipyards for building boats for the citizenry, but in 1661, a naval frigate was built at Dover Point for the British government. In Dover’s early history, shipping masts, dried fish, and beaver skins for Europe were the staples of the area’s economy. Lumber for barrels and casks was hewn in Dover sawmills and regularly shipped to the West Indies in trade for rum and spices. Dover Point thrived as a waterfront village for about 150 years, until the Industrial Revolution moved the center of activity north to the Cochecho River at present day downtown Dover.

As commerce increased with the West Indies, it was necessary to have several shipping points or wharves along the Fore River. The one at Hilton’s Point is the only one remaining today. It used to be known as the Town Wharf and many gundalows would have tied there to load and unload during its useful years. On the north side of Pomeroy Cove, Richard Waldron built his wharf and some old pilings are still in the mud today. Further upriver were the Hendersons, Varneys, and Hartford docks. All those shipping points made the river a very busy place with lumber, fish and barrel staves going out and molasses, sugar and rum coming in.

Leave Hilton Park-Right Turn to SPAULDING TURNPIKE

As the population increased, settlers gradually moved northward to Dover Neck. Pomeroy Cove was the accepted geographical boundary between Dover Point and Dover Neck. Dover Neck is the peninsula between the two rivers, defined by historian Jeremy Belknap as “about two miles long, and half a mile wide, rising gently along a fine road, and declining on each side like a ship’s deck.”

On the right is Pomeroy Cove as it exists today. Pomeroy Cove was partially filled in for the construction of the railroad and then the highway. A marker in the parking lot of the Department of Motor Vehicles, on the left, noting the location of the original landing location, will be seen on the return trip.

Right turn to DOVER POINT ROAD

As the population of Dover Point Increased, settlers gradually moved further up the peninsula of Dover Neck, the narrow strip of land between the Fore and Back Rivers. When Capt. Thomas Wiggin arrived at Pomeroy’s Cove with a second contingent of settlers in 1633, ten years after the Hiltons, he built his log house on “Captain’s Hill” half a mile up from the landing place. From this spot he could scan the three rivers and observe river traffic. This location is about where the highway overpass is now.

This road, which generally takes the high ground between the Piscataqua and Back Rivers, was in earlier days, called High Street. Roads along the rivers also received names appropriate to their locations. The road on the Back River side, our right, was known as Low Street. Roads on the Piscataqua side, our left, were called Fore River Lane and River Road. Later terminology, Back Road and Middle Road, have remained to this day. Much of these ancient highways have disappeared, although more recent streets follow portions of them.

Stop at Seacoast Furniture

The Seacoast Furniture store was formerly Riverview Hall. The Colemans who lived in the adjacent house constructed this building in the early 1900’s. The Colemans were the owners of the famous Coleman Spring, which supplied water to Dover’s first business street. Tom Coleman built Riverview Hall, a combination store and dance hall. It did not prosper, but was used later as a bunkhouse and dining room for the Fiske Brick Company, which was located at the waterfront below Riverview Hall.

As the migration moved up the Neck and more skilled colonists arrived, small industries were started on both High and Low Streets. In 1600, prior to settlement, New England was approximately 96% forested. The immense forest was cleared for farmland and the timber was used heavily for homes, ships, and barrel staves. There were cooperages, tanning pits, blacksmith shops, and a brewery. The first meetinghouse, a log structure that was used from 1633 to 1654, was located on Low Street. Its precise location is unknown but folklore places it somewhere near the present day site of the Dover Toll Booth. The meetinghouse had no bell so the town ordered that “Richard Pinckome shall beat the drumme on the Lord’s Day to give notice of the time of meeting.” The succession of meetinghouses followed the city’s population as it moved from Dover Point to the village of Cochecho, present day downtown Dover.

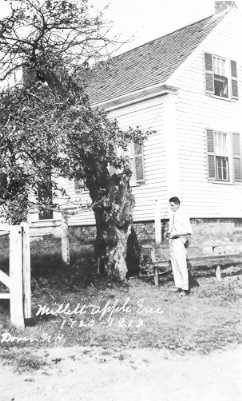

In 1720, Captain Thomas Millet arrived at Dover Neck with a small apple tree in a tub. The tree was planted not far from here, and grew to be 4’ in diameter with branches 8’ from the ground. It would bear 40-50 bushels of apples every year until its death in 1913. Wood from Millet’s Apple Tree was used to create the gavel for the Northam Colonists, Dover’s Historical Society. The gavel has been retired and is now on display in the Woodman Institute, as is a piece of wood from the tree itself.

Continue on DOVER POINT ROAD - Stop at Dover Neck School House

Social life was not entirely lacking for our early settlers. The novel “Becky” researched and written by a Dover girl show that one young man at Hilton Point courted a girl at Strawbery Banke, in Portsmouth, via rowboat, using the tides to advantage. They were eventually married at the Point with Indians and down river guests in attendance. As the number of children grew, the question of education became pertinent. Rev. Daniel Maud and his wife Marjorie were commissioned to conduct a school in their home on Captain’s Hill. This was Dover’s first schoolhouse and continued until 1655 when Mr. Maud passed away. Various other teachers took over until 1708 when a free Latin school was established in Portsmouth for the entire province.

As the town spread up river, various district schools were established by the Dover township to cover new areas. Eventually there were ten covering the entire city, including the Lower Neck School, which is seen here. Next door to the Schoolhouse is the Lower Neck Firehouse, which served as a meeting location for the Piscataqua Community Club.

Mr. and Mrs. Fred Poore, proprietors of the Pine Shore House on Dover point, and also the social leaders of the area, formed the Community Club for winter entertainment. One month the club would meet at the Upper Neck Schoolhouse and the next month at the Lower Neck Firehouse. Storms would never cancel the meetings. Locals would hitch up their horses, fill the flat bed sleds with hay and pack in with the ham, beans, and assorted pies. When the revelers arrived at the hall, the pot bellied stoves would be red hot and everyone would greet, meet, eat and square dance until midnight.

The Community Club carried on for years until housing developments took over Dover Point. The Club purchased the Schoolhouse next door to the Firehouse, but the festivities never quite matched the earlier days. After Mrs. Poore sold out, it was finally decided to close the books and sell to the Knights of Pythias, who now occupy the schoolhouse, and hold a 99-year least on the firehouse, which is owned by the City.

Continue on DOVER PONT ROAD-Stop for view of Meetinghouse Site

On the left of Dover Point Road is a historic marker indicating the site of Dover’s Second Meetinghouse. By the mid 1600’s, the first meetinghouse became too small, while at the same time, the population was shifting northward. In 1654, the second meetinghouse was built at Nutter’s Hill, on what was then High Street. The earth outline of the 1667 fortification around the meetinghouse is still visible.

Richard Waldron built the meetinghouse in exchange for timber rights. As Dover prospered, the remnants of the fine forest that covered this point of land gradually disappeared. In addition to the lumber industry, wood was also the main source of fuel for heating homes and cooking. Eventually, the Point became a lot of acreage of open fields, and cordwood was carted and boated in to meet demands. A picture taken in 1900 shows a scene of both rivers taken from Nutter Hill with a clear view all the way down to the tide water.

Continue on DOVER POINT ROAD

The Roberts Family Farm once encompassed this entire area, extending from river to river, including orchards, farmland, and woodland. The colonists used the area just north of the farm as a sheep and oxen pasture, as well as a training ground for the militia.

Thomas Roberts, a member of the Fishmonger’s guild in London, came over with the Hiltons on a business venture in the New World. It is said that Roberts’ wife was a sister of the Hiltons. When the settlement was taken over by Capt. Wiggin, the original party disbanded. Edward Hilton went to Newfields, William to Maine, and Thomas Roberts moved up the Neck to a new grant of land, bought from Indian Chief Tahanto. Roberts prospered, and from 1640-1643, was governor of the Dover Province, which included not only Dover proper, but also the present townships of Durham, Lee, Madbury, Somersworth, and Rollinsford, the greater part of Newington, and portions of Greenland and Newmarket.

Stop at First Settler’s Burying Ground

On the right, is the Roberts Cemetery, the first public burying ground in Dover, dating from 1633. All those who died earlier were buried on private land. This spot was the northern boundary of Dover Neck Village. The rust colored slate headstone at the far end of the second row of graves makes the final resting-place of Thomas Roberts. On the left, diagonally across the street from the Roberts Cemetery, is the Pinkham Cemetery, also known as the Quaker Cemetery, which dates from 1680.

Thomas Roberts’ two sons, John and Thomas, who had been appointed constables, acted under orders from the crown magistrate Waldon, in banishing three Quaker women who had been disrupting meetings in the First Parish. The Roberts’ boys, acting on orders to run the women out of town, tied them to the tail of an ox-cart and dragged them through the snow down to the ferry at Hilton’s Point and turned them over to another constable to continue to the next town. The women were whipped by the constable in each town they passed through from Dover to Boston, until they were out of jurisdiction. In Salisbury, Major Pike, stopped the persecution of the Quaker women. Dr. Walter Barefoot, who was one of the company that went with the constable, dressed their wounds and brought them back to the Piscataqua, setting them up on the Maine side of the river.

Thomas Roberts was heartbroken that his own sons should carry out the orders and never got over the shame or hurt. Eventually the Quaker women came back to Dover and established a church, and one third of the Dover citizenry became Quaker. Dover’s first Quaker Meeting House was built in 1680, just north of the Pinkham Cemetery site. The Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier immortalized the three women in his poem “How They Drove the Quaker Women from Dover”.

“The tossing spray of Cochecho’s falls

Hardened to ice on its icy walls,

As through Dover town, in the chill gray dawn,

Three women passed, as the cart tail drawn,

Bared to the waist, for the north wind’s grip

And keener sting of the constables whip,

The blood that followed each hissing blow

Froze as it sprinkled the winter snow.

Priest and ruler, boy and maiden

Followed the dismal cavalcade:

And from door and window, open thrown,

Looked and wondered, gaffer and crone.”

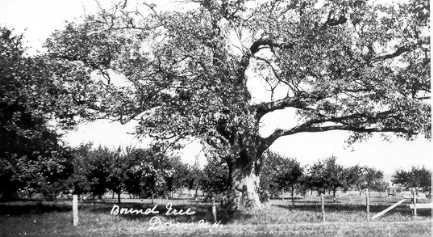

On the boundary line between the farms of Joseph Roberts and Thomas Roberts was a 300-year-old tree known as the “Bound Oak.” When the Dover fleet of sailing ships that carried ice and supplies to the West Indies returned to Dover, many slaves escaping plantations in the islands settled in Dover and were employed by local farmers. Joseph Roberts had a negro helper, a giant named Caesar. His brother Thomas had another by the name of Pompy. They were both good workers and the brothers boasted of their abilities. Finally, a wrestling match was set up to test the prowess. The match was arranged in the shade of the mammoth Bound Oak. Neighbors were invited and brought picnic baskets to the event. Cider and West Indies rum was supplied to all. It was a grand day in September when Caesar and Pompy wrestled for hours with people cheering their favorite. Finally, Caesar threw Poppy on his own side and was declared winner. The spectators had a fine time and congratulated the two men on their good sportsmanship. The Bound Oak is gone now and this part of the farm in now Riverside Drive.

Left turn – Continue on BELLAMY LANE

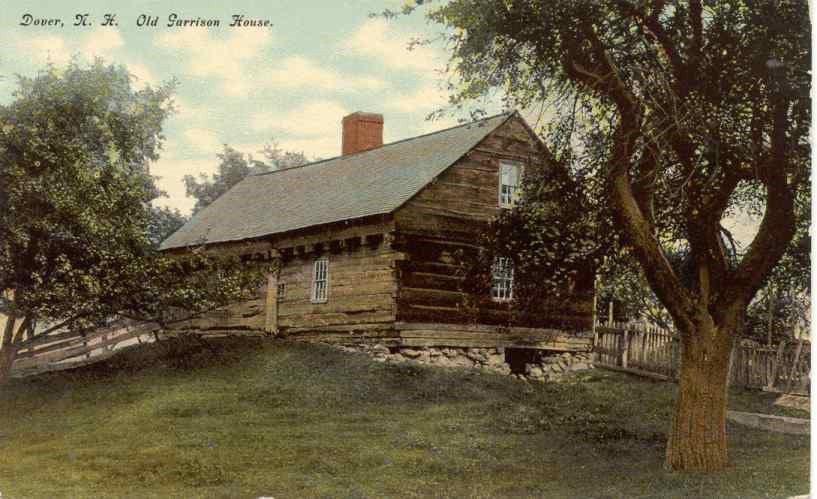

We are now on Bellamy Lane, which parallels the former Bellamy Station Road. On the south side of New Bellamy Lane is the site of the former Pinkham Garrison, one of Dover’s earliest fortifications. Certain homes of prominent Dover citizens, ordered to be fortified against Indian attack, or “garrisoned” to serve as protection for local residents. On the opposite side of the Back River was the Damm Garrison. Of sixteen garrisons built in the area, only the Damm Garrison survives today. Built around 1675, it is the oldest building in Dover. Today it is sheltered under a protective canopy at the Woodman Institute. In October 1915, over the course of one week, the 40’ x 22’ house was relocated three miles from its original site, moved by four men using rollers, with one horse doing the hauling.

Left turn – Continue on SPUR ROAD

Spur Road received its name because it served as a spur access road for the railroad company workers. The railroad connected the two main towns of Portsmouth and Dover by a span near the site of the present day General Sullivan Bridge. The railroad is long gone, however, portions of its roadbed now serve as the Spaulding Turnpike which was built in the 1950’s. The Spaulding Turnpike and Spur Road generally follow the route of the Portsmouth and Dover Railroad, which closely followed the original route of Low Street.

During the 1600’s, both the Back River and Fore River shores were lined with brickyards, which used the rivers to transport their raw materials and finished goods. Builders of past centuries held Dover bricks, made with its peculiar blue clay, in very high esteem. Clay was extracted by horse-drawn scoops, then shoveled into a mixer powered by a horse going around in a circle. The clay was mixed with prescribed amounts of sand and water, run into forms of 12 each, wheeled to a stacking area, and left to harden and weather. In mid-August, the kilns were prepared. The hardened bricks would be arranged in layers as high as thirty feet tall and begin the burning process. The French Canadians who were brought into the brickyards would tend to the fires while a local skilled burn master would instruct the tender to burn the proper amount of fuel. The fires were kept going for a week or until the bricks turned red and were properly hardened to the master’s satisfaction.

Dover bricks were hard and durable, and would last forever if properly mortared. Bricks from the Fiske Brick Company were used in both the Dover Library and present Junior High School. Much of the fine brick architecture in Boston was built with Dover brick, which was also shipped by boat to builders in faraway ports, including New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Portland. Brickmaking became a very large and profitable business, thanks in large part to the Piscataqua gundalows. Named for the Venetian gondolas, and indigenous to the Piscataqua River and Great Bay, the gundalows were designed to carry heavy freight and passengers up and down the shallow rivers. The gundalows, with their special breed of boatsmen, carried bricks and granite down the coast to Boston and Cape Cod, and returned the following week with a load of bog hay or meadow grass. Later, the gundalows were replaced with tugs towing two-mastered schooners, which were subsequently replaced with steam driven craft.

During the Brickyard era there was a lot of activity on the Neck, with about 25 yards operating on the waterfront. The Loughlins established the first brickyard on Dover Point, just to the right of the present Sullivan Bridge. Some of these brickyards were in operation into the 1900’s. The last bricks produced on the Bellamy, by Charles Belanger, were shipped by rail on the old Dover-Portsmouth branch of the B&M Railroad. The location of these old brickyards will always be visible on the waterfront because of the broken and discarded bricks lost overboard when the shippers loaded.

On the right is the western shore of Dover Neck. Today, the water we see is commonly called the Bellamy River. The origin of the name “Bellamy” is unclear, with two theories prevailing: one holds that the river was name for a servant of the farmer William Bellew (Bellew’s Man). Bellew was a landowner with twenty acres of land on the north side of the First Falls in 1644. The second opinion credits the name to an Indian named Sagamore who had a cornfield here in the early 1640’s. It seems the Indian was so fat he was nicknamed the “Belly-man” and the stream became known as Bellyman’s Bank in 1646.

The tidal portion of the Bellamy was originally known as Back River. With rough terrain and the lack of transportation other than boat, the settlement grew through the 1600’s into the 1700’s, with the chief mode of transportation by water. Many “slips” or landings were operated. Shipyards, fish weirs, ferries to the Maine side of the river, and all forms of waterfront operations were in business. Nutter’s Slip and Hall’s Slips were the two major landings on the Back River side of Dover Neck.

Stop at Hall’s Spring marker

Difficult to see, on the left, near the toll booths, is a small stone and plaque marking the historical Hall Spring. This notable spring was the source of a very fine vein of water. Hall Spring supplied the early sailing ships with water which would stay sweet in their casks, noted because it would not get brackish during the six to eight weeks it would take to get back to England. This spring was still active up until the time that the Spaulding Turnpike was built over it.

Continue on Spur Road

Crossing US Route 4, to the right, is the new Scammell Bridge. The original Scammell Bridge, named for a Durham Revolutionary Was hero, was built in the 1930’s. A fisherman who lived upstream of the bridge gave money to the state to construct the drawbridge so that he could reach the ocean from his home by boat. The drawbridge was permanently closed in the 1960’s. The original bridge was demolished in February 1198, replaced with the new larger structure.

The first bridge at this site was the Piscataqua Bridge. Built in 1794, the bridge connected Dover and Newington by way of Goat Island, which had a tavern for the benefit of weary travelers. In 1794 the bridge was opened and the tavern was advertised to be let as a “new, commodious double house, with a large, convenient stable, and a well that afforded an ample supply of water in the driest season.”

Straight to BOSTON HARBOR ROAD

Traveling along Boston Harbor Road, a clarification is in order of the road’s name. In the old days when people went to the Point by train, Joe Boston and Pete Stone had camps down there on the shore. Joe, who drove a delivery wagon for the J.S. Lothrop Corp., was six feet tall, very jovial and had a host of friends. Joe loved his camp and he loved a good party. When people went to a party at Joe Boston’s camp, there was a great desire to go again. The name Boston Harbor was coined, and that is how the road was named.

Stop at Department of Motor Vehicles

At the time of the Hilton landing, Pomeroy Cove extended from Piscataqua River to the present Motor Vehicle parking lot. The original landing at Pomeroy Cove has since been filled in due to railroad and highway construction. The marker at the corner of the parking lot commemorating the original 1623 landing place was relocated to the Department of Motor Vehicles site during the latest Spaulding Turnpike Construction.

Continue on BOSTON HARBOR ROAD

Below Pomeroy Cove was the area known geographically as Dover Point. At the beginning of this century there was a scattered settlement from the cove to the railroad bridge, including historic Dover family names such as the Cards, Morangs, Pinkhams, Robinsons, and the Dames. Capt. Jackie Saunders lived in a house in the area now between Boston Harbor Road and the Spaulding Turnpike. The renowned Newicks Restaurant on the right, celebrates its 50th anniversary in 1998.

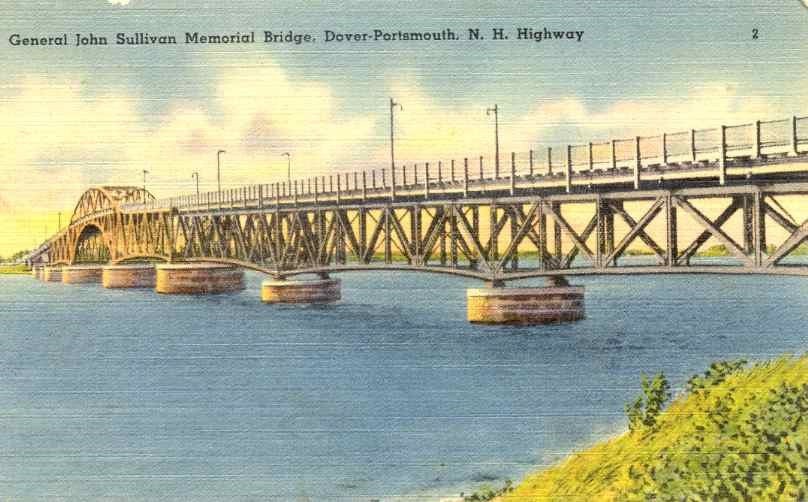

Continue under GENERAL SULLIVAN BRIDGE

The original General Sullivan Bridge was built in the 1930’s completing a highway link from Portsmouth to Concord. Like the Scammell Bridge, it was named for a Durham Revolutionary War hero. The original General Sullivan Bridge is now closed to traffic, open only to bicyclists, pedestrians, and anglers.

In the 1600’s, many ferries operated on the rivers. The first ferryman was Thomas Trickey, one of the first settlers in the Bloody Point area of Old Dover, now in Newington. He also ran a ferry to Everett’s Point, Old Kittery, now in Eliot.When Capt. John Knight assumed ownership in 1705, the fare was twelvepence for each man and horse and three pence for every single person without a horse. The Bloody Point Ferry continued operation until 1871, when the railroad bridge was built.

In the latter part of the nineteenth century, spurred by the Industrial Revolution, Portsmouth alemaker Frank Jones built the Portsmouth to Dover Railroad, including a pile bridge crossing the river from Newington to Hilton Point. Ground for the railroad was broken in 1872 and the first passenger went over the new Dover Point Bridge on Feb. 9, 1874. There was a station and toll house on the Newington side which is still standing today.

The coming of the railroad made a great difference to the people of Dover Point, replacing all ferry service at Dover Point. Instead of traveling by boat or team, people would walk to the station and board a train to either Dover or Portsmouth. Dover Point Station was one of four “flag stops” on the Portsmouth and Dover Railroad. The train only stopped if a flag was up to indicate that a passenger was waiting. There were flag stops or stations every two miles and people would walk to the one closest to their home. At the turn of this century, mail was dropped off at Ford’s Crossing, which was actually Jim Ford’s house. Jim Ford was the postmaster and residents got their mail by calling at Jim’s house. From Dover Point, the track ran on a trestle across Pomeroy Cove and then on to Dover via what is now Spur Road.

End Tour at HILTON PARK

In the 1950’s, the construction of the Spaulding Turnpike completed a progression from river to rail to roadway, which defined and shaped Dover Point and Dover Neck. Today, 375 years after the original settlement of Hilton Point, Hilton Park serves as a respite from the present and its monument as a reminder of the past.

Sources - Further Reading

Brighton, Raymond A.; They Came to Fish, 1973 (expanded 1979).

Colby, Solon B; Colby’s Indian History-Antiquities of the N.H. Indians, 1975.

Hawke, David Freeman; Everyday Life in Early America, 1988.

Johnson, Frances Ann; Introduction to New Hampshire, 1951.

Quint, Alonzo Hall; Historical Memoranda of Ancient Dover, N.H., 1900.

Robinson, J. Dennis; Seacoast Ramblings (Selected Articles).

Scales, John; Colonial Era History of Dover, New Hampshire, 1923.

Thompson, Mary; Landmarks in Ancient Dover, N.H., 1892 (reprinted 1965).

Life in the village

Throughout the village, everyone worked from dawn until dark, six days a week, and even on Sunday there were many chores to be done. In addition to the chores at home and the fish trade, there were always community jobs to be done. These included building grist mills and saw mills, constructing boats to get up and down the rivers, clearing rough trails, building carts, making bricks for chimneys, clearing land for buildings, crops, and pastures, organizing town government, attending to religious matters, educating children, and protecting themselves from wild animals.

It was the usual course for the fisheries in those days for about one third of each crew to live ashore and attend to the cutting, drying, and curing of the catch. The remainder cruised about the ocean searching for mackerel and cod. Shelter for the large number of shoremen would be essential and numerous cabins were built for their accommodations. Fishing wharves were built as soon as the first cabins were put up, if not sooner. Young folks of those days spent much time watching fishermen return from the Isles of Shoals with a day’s catch of two to three hundred cod or mackerel. The fish were tossed onto the wharves then carried to open sheds where they were split, salted, and dried on wooden platforms called flakes.

In order to support the fishing trade, supplemental industries evolved at Dover Point. A few men made bricks from clay, which was taken from the banks of the Fore and Back Rivers. The brick makers dug a supply of clay from the rivers in the fall and spring. When bricks were needed, some of the clay was spread out to dry, and then it was put into soak pits where water was sprinkled over it. When it “slaked” like lime, it was put into molds and left to harden into bricks. A significant brick industry evolved out of these yards. A brewery was established as early as 1640 at Fore River. Job Clement around 1653 established Dover’s first tannery. Trickey’s Ferry operated from Dover Point to Newington as early as 1640. Captain Walter Barefoot, who operated a ferry slip on Fore River in 1652, was also Dover’s first physician. Ship and boat building engaged the time of many men by 1650. They made boats for fishing, gundalows and ferries for river travel, and even ships for trading along the coast and with England. Nearby forests and Richard Waldron’s sawmill at the falls made lumber easy to get. The shipyards were sheltered in the bays and coves along Dover Neck. There is no record of when the first vessel was built in Dover, but it was certainly at a very early period after the lumbermen began to cut the forests. Records show that a frigate was built in a cove where the Cochecho empties into the Fore River, prior to 1650.

Dover Point Village was laid out similar to English villages familiar to the immigrant settlers, stretching along a single street with lanes leading from the street down to the water. The street broadened midway to make way for a green where the meetinghouse would stand and later a burial ground would be marked by headstones. The greens then hardly resembled those seen in New England to today. Cows grazed on them and the local militia trained there. Continual trampling left most greens anything but green, looking more like a wide muddy paddock.

The narrow house lots that flanked the street kept neighbors close, within walking distance of each other and the meetinghouse. The lots varied in size, but were large enough to hold a garden, a small orchard, and enough pasture for the family’s cow or two when the town’s herdsman brought them back to be penned up for the night. In general, each settler owned his village lot outright and the land assigned to him elsewhere in town. The size of a householder’s holdings depended on his social status.

There is no question that the economy of Dover Point was centered on the fishing business. The fact that best emphasizes the importance of fishing to the early village is the Town Record of February 26, 1644. It states that Edward Starbuck, Richard Walderne, and William Furber are to be wearsmen (weirsmen) for the Cochecho Falls and River in exchange for a rent of 6000 alewives to the Town. The first 6000 fish were for the church and the next 6000 for the weirsmen themselves. After that, the fish were to be distributed to the church officers, then to all that bear office in the commonwealth, and lastly, to the “most ancient inhabitants”, so each man had a thousand fish.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.