Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

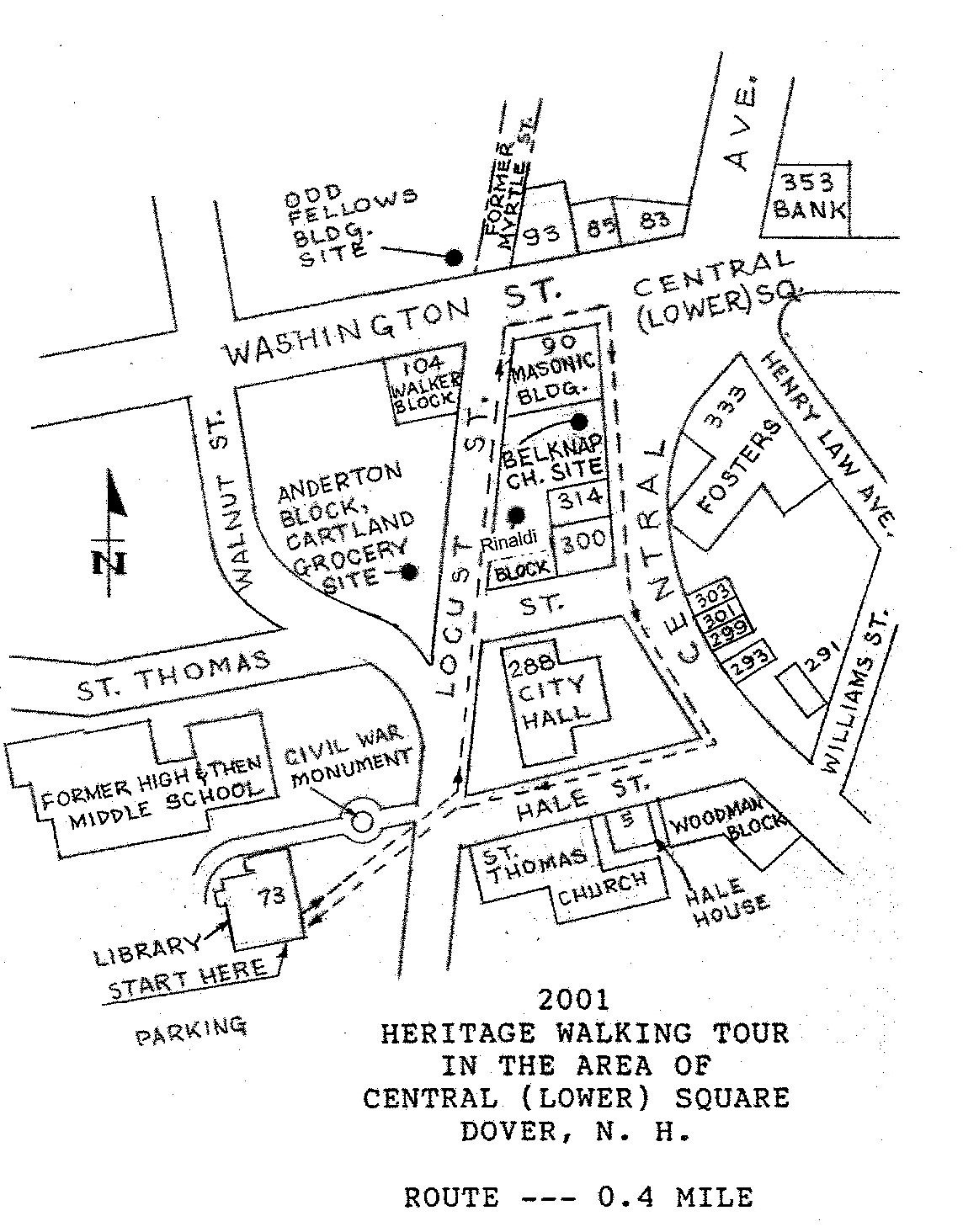

2001 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet October 7,2001 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 2001.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

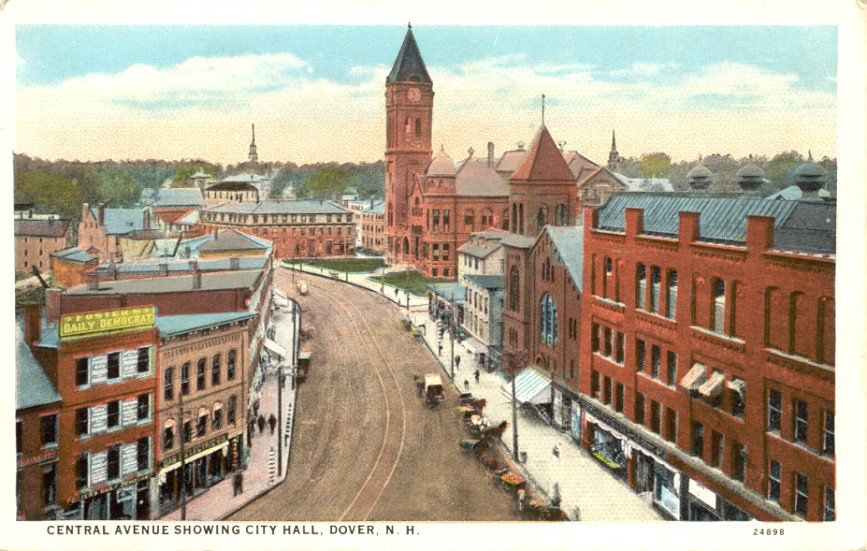

Central Square

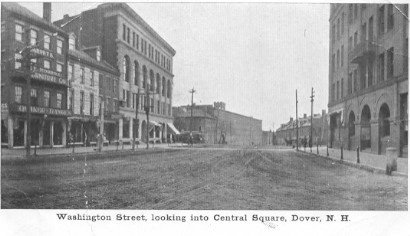

Locust Street, Central Avenue and Washington Street

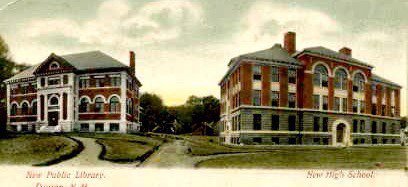

DOVER PUBLIC LIBRARY

Dover’s first library existed before 1776 with a social library (much like a literary club), followed by a circulating library with membership fees, a library association with annual subscriptions, and, finally, in August 1883, an incorporated public library. The Public Library was housed at various locations including the Cocheco Manufacturing Company (1884), the Odd Fellows building on Washington Street (1889) and the basement of City Hall (1899). The present building, designed by architects Randlett & Griffin, was constructed for $29,675, with money donated by Andrew Carnegie, and land given by the Franklin Academy from the estate of William Hale, Jr. The foundation was laid in the fall of 1903, the brick work put up the next spring, and the building was completed in June 1905. The formal dedication was held July 19, 1905. The 5600-square-foot addition was constructed in 1988, and internal renovations to the original building were made between 1986 and 1990.

SOLDIERS & SAILORS CIVIL WAR MONUMENT

After the new High School and the Public Library were opened in 1905, there arose a community fervor to place a memorial in the middle of the circle that joined the driveways of these two new magnificent city buildings. Local citizens wished to honor those who had served in the nation’s Civil War. Led by veterans from the local chapter of the G.A.R.(Grand Army of the Republic) and members of the Women’s Relief Corps, the proposal was embraced by Colonel Daniel Hall of Summer Street. Himself a veteran, Col. Hall donated the funds for the creation of a Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. The 41’6” monument was designed and built by Lewis J. White of Quincy, Massachusetts and was made with granite from Barre, Vermont. The army and navy veterans that stand on either side are made of bronze. The statue was dedicated on October 25, 1912 after a parade in which over 150 Civil War veterans marched from the railroad station to the unveiling spot. A large crowd gathered to hear martial music and patriotic speeches by Col. Hall and other city and military dignitaries. One later account says that a time capsule was embedded in the granite behind the letter “V” in the word “Dover”, but the newspaper articles of the time do not report this.

DOVER HIGH SCHOOL

Having outgrown the first Dover High School, which was located on Chestnut Street, the City Council appropriated, in 1903, $50,000 for a new high school. It was to be constructed on part of the Hale lot on Locust Street, land which had been donated to the City by the Trustees of the Franklin Academy. The new school would be adjacent to the new public library, also in the planning stages. The School Board also voted to spend an additional $18,255 to acquire additional land bordering St. Thomas Street. Six homes were purchased on that street and razed before the project began.

Architect Alvah T. Ramsdell was hired and his plans were adopted in early 1904. A groundbreaking ceremony was held on May 9, 1904 and the cornerstone was laid in place by the Class of ’04 on August 31st. Completion was scheduled for the beginning of the school year in September, 1905.

When the school was finished and equipped with furniture and fixtures (including the first telephones in a Dover school), total cost of the project was $83,503. On September 7, 1905 Mayor John Nealley officially transferred possession of the building from the City to the School Board. Dover’s population at that time was about 15,000 and DHS enrollment was 276. Students registered for one of four tracks of study (Classical, Scientific, General, or Commercial) and the school day ran from 8:20 am to 1:10 pm. There were ten teachers at Dover High School, each earning an average salary of $850.

By the mid-1920’s, Dover High was cramped and inadequate. There was a strong emphasis on the Mechanical and Manual Arts program and more classroom space was needed for labs and shops. An active physical education program led to a need for a gymnasium. In 1927, the New High School Annex was constructed at a cost of $235,000. Designed by local architect J. Edward Richardson, the annex held the 12,000 square foot Mechanical Arts Department, instructors’ offices, the school nurse, the band director, a 60’ X 90” gym, and seven additional classrooms. Dover High’s new capacity was 650 students.

By the 1960s, the school was overcrowded again. A new Dover High School was constructed on Durham Road and the last class graduated from the old DHS in 1967. The next year, it became the Dover Junior High School (which became known as the Dover Middle School in the mid- 90s). In 1981, another renovation project was completed for $2.5 million. This project provided new library and cafeteria space, additional classrooms, and infrastructure improvements including handicapped access. But after nearly a century of use, even these enhancements were but a temporary remedy. In 1999, the City voted to build a new Dover Middle School and it opened on the Durham Road in September 2000. The old and dilapidated school on Locust Street reverted back to city possession.

At present, city staff and councilors are studying the building for potential reuses. Two city departments, Human Services and Legal, have recently relocated their offices there; further architectural studies will determine future tenants, space arrangements, and improvements and renovations to come.

East Side of Locust Street

William King Atkinson (1765-1828), a lawyer and prominent landowner, was one of the founders and the first President of Strafford National Bank. Mr. Atkinson lived on the corner of Central Avenue and St. Thomas Street when he died in 1820. His wife, Abigail, died in 1838.

After Abigail’s death, the bank foreclosed on the property which was then broken up into smaller lots and sold to pay debt. The former Atkinson homestead and surrounding land were purchased by Asa Freeman, who had married Atkinson’s daughter, Frances. This land had 120-foot frontage on Central Street running north from St. Thomas and ran from the Avenue to Locust Street. Mr. Freeman divided this land into two parcels, each with sixty foot frontage on Central Street. He sold the north parcel to Joseph Nesmith, who resold it in 1867 to John C. Hughes.

Asa Freeman died in 1872, the same year his widow, Frances, sold the south half of this property to Henry Law. In 1885, Margaret Hughes (widow of John C.) sold the north parcel to Mr. Law, so that Mr. Law now owned the entire lot bought by Asa Freeman in 1838.

Mr. Law constructed several buildings on his property; most were multistory and had store fronts on the first floor with living spaces above. One of his tenants was Guiseppe Rinaldi, who operated a fruit store and restaurant at 32-34 Locus Street. After Henry Law died in 1938, all his real estate was sold by the executor of his estate. In 1939, Mr. Rinaldi bought the building on Locust Street and it became known as the Rinaldi Block.

GLIDDEN BLOCK – 20-24 LOCUST STREET

Around 1875, John A. Glidden, who ran a saw mill at the foot of Washington Street, established a coffin warehouse at this location. A few years later, he moved into the building and established an undertaker business here. Around 1908, Leslie W. Glidden, nephew of John, joined him in the business and the name was changed to Glidden & Glidden. John Glidden died in 1913 and Leslie Glidden later joined with Ralph Wiggin to found Glidden & Wiggin, funeral directors on Orchard Street. This business later moved to 655 Central Avenue and still operates from that location under the name of Wiggin, Purdy, McCooey, Dion Funereal Home.

ANDERTON BLOCK – 34-45 LOCUST STREET

In 1867, William H. Smith had a livery stable here but did not own the lot. The lot was owned by Frances Freeman, the widow of Asa Freeman and daughter of William K. Atkinson. In 1868, Mrs. Freeman sold the lot to her daughter, Abby Atkinson Pike, also a widow, of Hanover, NH. In 1889, Mrs. Pike sold it to Washington Anderton, who was the agent for the print works.

The land which Mr. Anderton acquired ran from Locust Street to Walnut Street. Mr. Anderton built a large two-story building on the lot, which had several store fronts facing Locust Street.

Around 1890, the grocery firm of Tasker and Cartland moved from their previous location at 79 Washington Street (Freeman Block) to 43 Locust Street. In 1898, Mr. William F. Cartland became the sole proprietor of the business. Under Mr. Cartland’s leadership, the business grew very rapidly so that by 1905 it occupied the entire building. The company sold groceries both wholesale and retail and owned stores at 3 Silver Street, 7 Chestnut Street and 23 Ham Street. Mr. Cartland retired in 1917 and turned the business over to one of his employees, Moses Howard Cartland, who four years later died when he shot himself in the head at his home at 155 Silver Street. Moses Cartland’s wife continued the business until she died in 1935.

After the Cartland Grocery Company left the building, the second floor, which had been used to store groceries, became a grange hall for about 10 years. After World War II, it became a restaurant and banquet hall known as the Esquire Club, with dancing on Saturday nights. About 1952, the city took over the space and used it for the Recreation Department. They remained there until they took over the old Armory on Washington Street in 1963. The building was taken down in 1986.

PUBLIC MARKET – 1932-1975

In 1931, Peter Colokathis owned a wholesale fruit business at 1 Payne Street. About 1933, he opened a grocery store known as Public Market in the new building which Mr. Seavey had built for Seavey Hardware. The store remained there until the mid 1940’s when Seavey Hardware Company (then owned by Mr. Dunnington and Mr. Smalley) decided to use the location for a gift store.

Mr. Colokathis moved his business to 17 Locust Street. In 1963, when the Dover Federal Savings Bank bought the building at 17 Locust Street and had it taken down to provide a parking lot for the bank, Mr. Colokathis moved Public Market to 93 Washington Street.

In 1975, the Urban Renewal project planned to demolish the building at 93 Washington Street. About this time, Mr. Colokathis retired and the Public Market went out of business. A group of concerned Dover citizens launched a campaign to save some of the buildings in the Urban Renewal area and this building was saved.

MYRTLE STREET AND THE ODD FELLOW BUILDING

Just left of 93 Washington Street, where McDuffee Insurance Agency is today, is a path leading up the hill to the Orchard Street parking lot. This used to be Myrtle Street. It was first listed in the Dover Directory of 1846 as running “from Washington Street east of the Star Office north to Orchard Street.” Dover’s 1851 map shows it extending south of Washington Street for a short distance. That part of the street became the lower end of Locust Street when it joined Washington Street.

To the left of the “Myrtle Street” pathway, in the Handy Hardware parking lot, is the site of the Odd Fellows Building. In 1843, the Free Will Baptist Printing establishment, in conjunction with the Washington Street Free Will Baptist Church, constructed a two-and-a-half story Greek revival-style building here. The printery used the ground floor and published a weekly religious newspaper called “The Morning Star.” It also published a semi-monthly paper for young people called “The Myrtle.” The church held its meetings on the second floor.

In 1868, the printer needed more room, so the church sold its share and built a new church on the corner of Washington and Fayette Streets. The printer modified the building, a mid-19th century fire caused further changes, and it was eventually rebuilt as a four-story building with a mansard-style roof. In 1869, the printer began leasing part of the building to the Odd Fellows organization. Eventually, the printer moved to Boston. The Odd Fellows (I.O.O.F.) bought the building in 1885 and completed $3,000 worth of renovations. Several rooms in the building served as home to the Dover Public Library from 1886 to 1891. Whiting’s Stationery was the last business housed there.

In 1974, as Dover’s Urban Renewal was taking shape, the I.O.O.F. sold the building to the Dover Housing Authority and moved to a new building on Cataract Avenue. The building was torn down in 1978 since no buyer could be found to develop and restore it.

THE WALKER BLOCK – 104 WASHINGTON STREET

The Walker Block was named for the man who built it, Joseph Albert Walker of Portsmouth. Mr. Walker bought the land (with buildings) on this corner from Russell Wiggin (a partner in Wiggins & Stevens – glue and sandpaper manufacturers) in 1878, and built the three-story brick building shortly thereafter. In 1896, Mr. Walker sold the building to Valentine Mathes of Dover, a lumber dealer and builder. The building remained in the Mathes family until 1952 when it was purchased by the Dover Cooperative Bank. The bank had been a tenant in the building since 1906, having moved from the Masonic Building after the fire at that location.

There was a fire in 104 Washington Street in January 1924 in which one person, Fred W. George, the janitor, died. At the time of the fire, the third floor served as the club room for the St. Charles Club. In 1954, the bank removed the third floor, which at that time was used as a function hall known as the Crystal Ballroom.

In the early 1950’s, the name of the Bank was changed to Dover Federal Savings & Loan Association. In 1972, the bank moved to the new building they had built at 633 Central Avenue.

90 WASHINGTON STREET

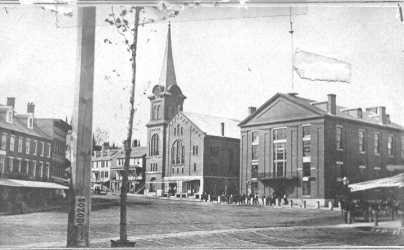

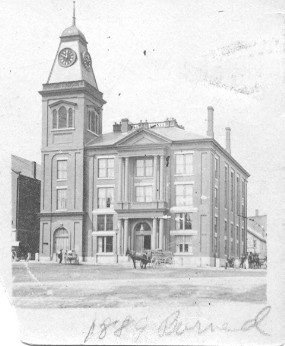

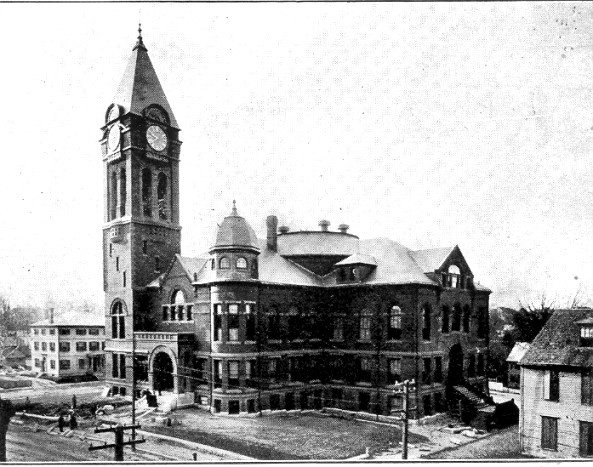

Dover’s first town hall stood on the site of the building at 90 Washington Street.

Built in 1842, it burned in 1866, was rebuilt shortly afterward, and burned once again in 1889, leading to the nickname “the Hot Corner.” The loss of the second building was scarcely a loss. As a newspaper at the time reported, “When the building was flat all seemed well pleased for it was an abortion in plan and construction…Its destruction was little regretted by our citizens.”

Perhaps feeling that this location was doomed to disaster, the city fathers built the third municipal structure, the Opera House up the street on Central Avenue in 1891.

The Masonic organizations, the Strafford Lodge and the Moses Paul Lodge, which had been housed in various locations around downtown Dover, decided to build their Temple here, where it was completed in 1890. Perhaps the site was doomed after all, as a third fire occurred here March 29, 1906, destroying the entire structure.

The present Masonic Temple, a Romanesque revival design costing $75,000, was rebuilt in 1907 and rededicated in 1908.

The Masonic lodges moved out in 1989 and later sold the building. The Moses Paul Lodge is now housed on Pearl Street; the Strafford Lodge is on Sixth Street. The former temple building now houses commercial interests on all floors.

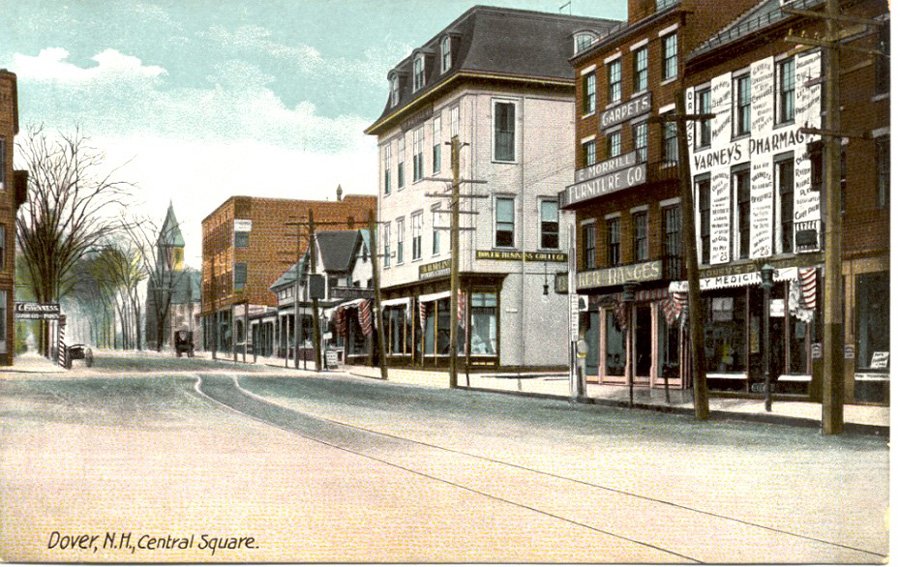

93-95 WASHINGTON STREET

This block of buildings has had a long and commercially successful history. Washington Street, itself, was established in 1826 and, due to its proximity to the mill, was mostly residential. By 1843, 93 Washington Street – the Public Market Building was built and the area began to develop commercially.

This block of buildings has been home to quite a diverse group of enterprises, such as the Public Market, Strafford National Bank and the Savings Bank for Strafford County, Sweetland restaurant, a sewing machine shop, W. Morrill Furniture company and an Army-Navy surplus store.

E. Morrill Furniture Company, dealers in furniture, carpets, bedding, draperies, curtains, and upholstery goods was housed at 95 Washington from 1846 to 1920. An ad for the store notes that “accuracy and economy are combined in the various processes of production, and explains in great measure the ability of the company to supply thoroughly first-class goods at bottom prices.”

By 1895, the two banks had outgrown the space in the brick building and voted to hire local architect Alvah T. Ramsdell to erect a larger building to house the bank. The construction was of Milford pink granite with oak and mahogany interior finishing and has been the cornerstone of Washington Street ever since.

Alvah T. Ramsdell

BANK OF NEW HAMPSHIRE BUILDING (353 CENTRAL AVENUE)

In 1940, Harry Farnham, the proprietor of Farnham’s clothing store, bought this lot from the Pacific Mills and built the building that now stands here. This building was known for many years as the Farnham Building.

In the 1950’s, this building was occupied by a First National Store, Ralph Pill Electric, and a Sears Order Store on the ground floor, with a lawyer’s office and real estate offices above.

In 1959, Harry Farmhan sold the building to the Strafford National Bank, and both the Strafford National and the Strafford Savings Bank moved to this location in 1963. The Strafford Savings Bank merged with the Granite State Savings Bank to form Southeast Bank for Savings, and they built a new building at 140 Washington Street across from the Post Office. Later, the Strafford National Bank became part of the First National Bank of Portsmouth, which is now Bank of New Hampshire.

“TROLLEY” CARS

Dover was the first city in New Hampshire to have an electric street railway, which started operations in 1890 under the name of Union Street Railway. They operated “trolleys” from Sawyer’s Bridge in Somersworth. The name was changed to Union Electric Railway and in 1900 this line became part of the Dover, Somersworth, and Rochester Street railway.

In the early 1900’s, as part of an expansion plan, the D.S.& R. built a loop that went up Washington Street, over Arch Street, and down Silver Street. The cars ran both ways on this loop. So in the early part of the twentieth century, you could stand on the corner and watch the trolley cars run up and down Central Avenue and also up and down Washington Street. In the center of town, the tracks usually ran in the center of the street.

FOSTER’S BLOCK (293 CENTRAL AVENUE NORTH TO 333)

Joshua Lane Foster was a successful architect in Concord. Driven by a lifelong interest in politics he came to Dover in 1858 and bought an interest in the Dover Gazette and Strafford Advertiser, which he kept until 1861. He returned to his architectural profession for two years, then started a paper in Portsmouth in 1863.

Foster was a staunch Democrat during the Civil War – a position viewed by many as support for the Confederacy. In 1865, at the end of the Civil War, a rejoicing but riotous crowd of civilians and sailors from Portsmouth Navy Yard converged on his Daniel Street printing plant intent on punishing Joshua for his views. When the crowd learned that he escaped they destroyed the printing machinery and set out to lynch Joshua. Luckily, they didn’t find him.

In 1872 he began Foster’s Weekly Democrat in Dover. The first issue of the current Foster’s Daily Democrat was published in 1873. Foster’s is the oldest, and possibly the only, daily newspaper in America to carry its founding family’s name.

In 1872 the newspaper was located first in the old Morrill Block. In 1876 it moved to the Williams Block on Waldron Street. Two years later it was in the Woodman Block, also on Waldron Street, and, in 1883, in the Cocheco Block on Washington Street.

In 1900 the paper moved to its present location. In 1950 expansion began when an old house in the rear of the original plant was purchased to provide a parking area. Later expansions continued to create the present span of 293 Central Avenue north to 333. Several four-story buildings, including Bernard Block in 1973, were torn down to achieve the current complex.

Among the earlier tenants of the area were Eddie’s Dinette (formerly Nick’s Lunch and Pacific Lunch), Dan & Sons Barbers, and Carswell Auto Parts.

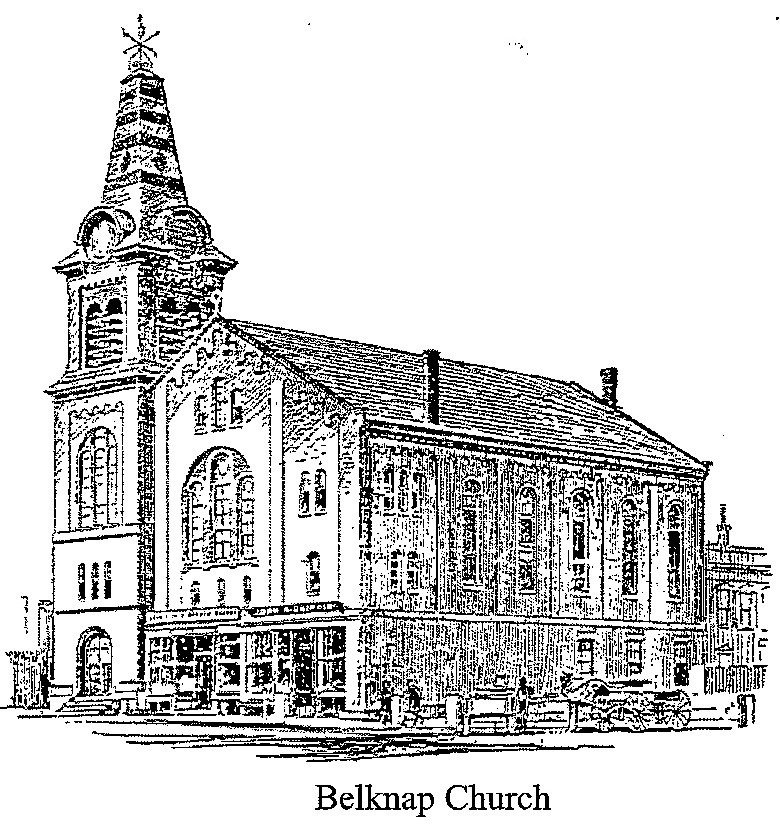

BELKNAP CHURCH SITE

In 1856, a group of more conservative members of the First Parish Church, with their Pastor, Reverend Benjamin Parsons, left to establish a new church. For the first two years, this group met at City Hall next door. In 1858, Reverend Parsons bought this lot from William Estes for $5000 and sold it about three months later to the Belknap Society for the same amount. The Society built a church here, which was dedicated December 29, 1859.

The main entrance to the church was on the left front corner; to the right of this were two store fronts which the church rented to local business owners. The church closed in 1881 and was severely damaged in the 1889 City Hall fire next door. It was subsequently repaired and services were again held until a second closing in 1896. The church suffered damage during the Masonic Temple fire of 1906. Once more it was repaired and reopened in 1909. In 1911, the church closed permanently, although members of the Belknap Society continued to meet until 1963.

Even though the church was closed, the Society continued to rent the two storefronts. The S.D. Sundeen company moved to this building in 1936 and remained here until about 1954, when Mr. Sundeen bought the lot next door and built a new building there.

In July, 1964, the Belknap Society deeded this property to the New Hampshire Congregational-Christian Conference. In December of the same year, the Conference sold the property to the City of Dover. In 1965, the City paid the Noonan Wrecking Company of Peabody, Ma $6,780 to demolish the building so a parking lot could be built on the site.

CITY HALL BLOCK

Over the years, many transformations have taken place in this area. In the late 1700’s, two men came to town who would become prominent in its affairs, particularly in connection with Dover’s first bank. One was William King Atkinson, the other was William Hale. They bought properties side by side between what are now Washington Street and Hale Street, running from Central Avenue to Atkinson Street in the other direction. They both built houses on Central Avenue. The Atkinson House is gone, while the Hale House remains in a different location. The Hale House was built in 1806 on the site of the present City Hall. In 1827 Hale Street was established and Locust Street was extended from Silver Street to meet it. A few years later William Hale, Jr., built his house on the site where the Library now stands.

In 1832, the Episcopal Church was organized in Dover. In 1840 the church purchased land adjacent to William Hale and built a wooden church, the first St. Thomas Church. St. Thomas Street and Atkinson Street was established, thus opening the area for the building of a number of houses. The Atkinson House passed to William King’s daughter, Mrs. Asa Freeman, and eventually was removed for Seavey’s Hardware Store.

At that time that the Town Hall at the corner of Central Avenue and Washington Street burned in 1889, this block was jointly owned by Sarah Low, famous Civil War nurse and granddaughter of William Hale, and the church.

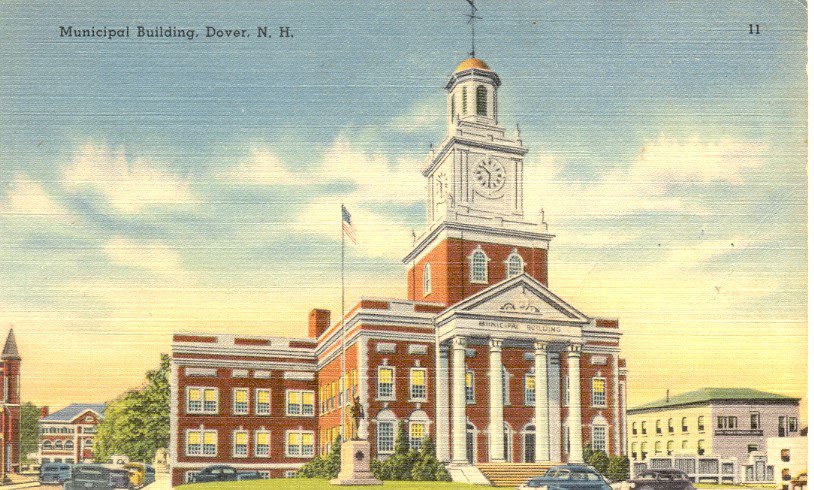

The two owners sold this land to the city for the site of a new city hall. The wooden church was razed, the Hale House was moved to its present location at 5 Hale Street, and the existing stone church was built adjacent to it. A new combined City Hall and Opera House was built on the vacated block in 1891.

Built at a cost of $250,000, the “Opera House” seated 1800 people. It featured a rising and falling floor, three-tiered balconies with velvet curtains and brass rails, and a chandelier containing 95 electric bulbs. Motion pictures were shown here as early as 1896, and well-known entertainers such as Alfred Lunt and John Phillip Sousa’s bank performed on its stage. The Opera House also hosted local events, including high school plays and proms. The building burned in 1933.

The present City Hall, dedicated in December, 1935, was designed to be fireproof. No wood was used in its construction except for interior finishing. Built for $300,000, this Georgian Colonial structure contains 1 million bricks, 190 tons of steel, and 16 fireproof vaults. The auditorium holds 900 people. The mural outside of the auditorium was painted in 1937-38 by WPA artist Gladys Brennigan. Measuring 9 ½ feet by 30 feet, it depicts “Early Days in Dover.” The bell in the 80-foot tower weighs 3500 pounds and is the original bell from the Opera House. Although severely damaged in the 1933 fire, it was recast and re-installed in the new municipal building. The bell was last rung on July 4, 1976.

WOODMAN BLOCK – 278-286 CENTRAL AVENUE

This large commercial block was built ca. 1895 by Theodore Woodman, a local real estate magnate who owned many apartment buildings and much acreage around Dover. Theordore was the son of Samuel and Lydia (Rollins) Woodman of Dover. He was born in 1841 and at his death on October 11, 1912, was the last surviving member of that branch of the Woodman family. He took great pride in his city, serving as a city councilor and as a representative in the NH Legislature from this district. He also served on the Dover School Board and, in his will, donated $10,000 for the land on which sits the present Woodman Park School.

He was also a trustee of the Wentworth Home, president of the Dover Board of Trade, and member of the Bellamy Club. He never married, but did adopt a daughter, Miss Leah Hutchins. They lived at 191 Central Avenue.

The Woodman Block was called “imposing” at the time it was built. Its turn-of-the-century architecture, notable by the large-windowed storefronts, detailed cornice and lathework trim, and colorful Mansard-roof, stood at the forefront of modern Dover business establishments. Upstairs, Woodman offered “good tenements for the masses at low rentals” and was considered “a just and liberal landlord” who bought each tenant a Christmas tree every year. The Woodman Block stands today little-changed, in either appearance or function, from its debut at the turn of the 20th century.

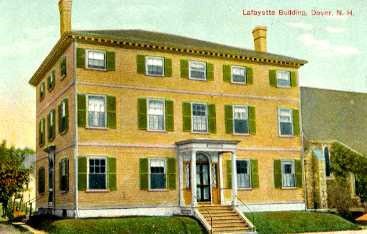

HALE HOUSE

The William Hale House, also known at the “Lafayette House” in memory of Lafayette’s stay here during his 1825 visit to Dover, was moved to this location at 5 Hale Street prior to 1891. The house was built in 1806 by George and Edward Pendexter; the exterior was a copy of the Edward Cutts House in Portsmouth. This is the oldest of the large Federal-style houses in Dover. Mr. Hale was a prominent Dover businessman and representative to the US Congress for several years prior to 1816. As a result, he not only entertained General Lafayette and his son in 1825, but also President Monroe on his visit of 1817. St. Thomas Church bought the house for a Parish House in 1901. The building was named to the National Register of Historic Places in December 1980.

ST. THOMAS EPISCOPAL CHURCH

The church was designed by the famous Boston architect Henry Vaughn; its cornerstone was laid in 1891. Stones collected in the Durham fields were used in the tower, and a quarry in Rochester supplied the granite. The bell and organ from the first church on Central Avenue were reused in the new building.

The addition behind the church and Hale House was constructed in 1950.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.