Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

2002 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet September 29, 2002 by the Dover Heritage Group, Dover, NH, c. 2002.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

September 29, 2002

Train Station

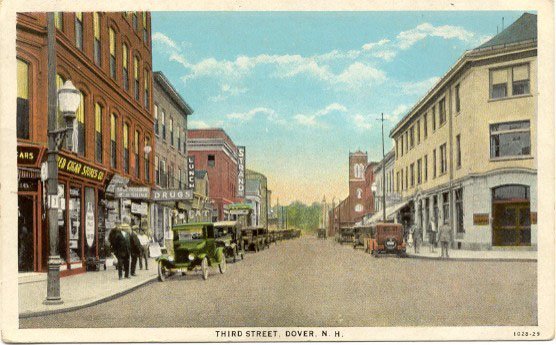

Third Street

Dover, New Hampshire

A Brief History of the Railroad in Dover

The first chartered railroad in New Hampshire ran from Boston to Lowell in 1830. By late in 1837, the railroad had been extended to the New Hampshire state line.

In 1838, Dover voters gave permission for the B&M tracks to pass through Dover. The Dover Gazette lobbied against it, saying the railroad would put men out of work who rode the stages and coasting vessels. Dover would “be turned into a town of idlers, under a tyrant’s power.”

The track was completed to Coffin’s Cut in Dover (at the intersection of Washington and Arch Streets) in August, 1841. On the east side of the track were the passenger and freight stations. From there, passengers and cargo were transported to town by horse-pulled omnibus or wagon.

The first train arrived on September 1, 1841, carrying a number of stockholders of the railroad. Although it was a stormy day, a large crowd of spectators turned out, both at the station and along the route from Newmarket. Most had never seen a train before and, according to a newspaper account of the day, one man was heard to remark, “You can’t fool me. I know there’s a horse in there somewhere!”

Since the station was unfinished, and further grading operations were necessary on the tracks, the trains did not run regularly at first.

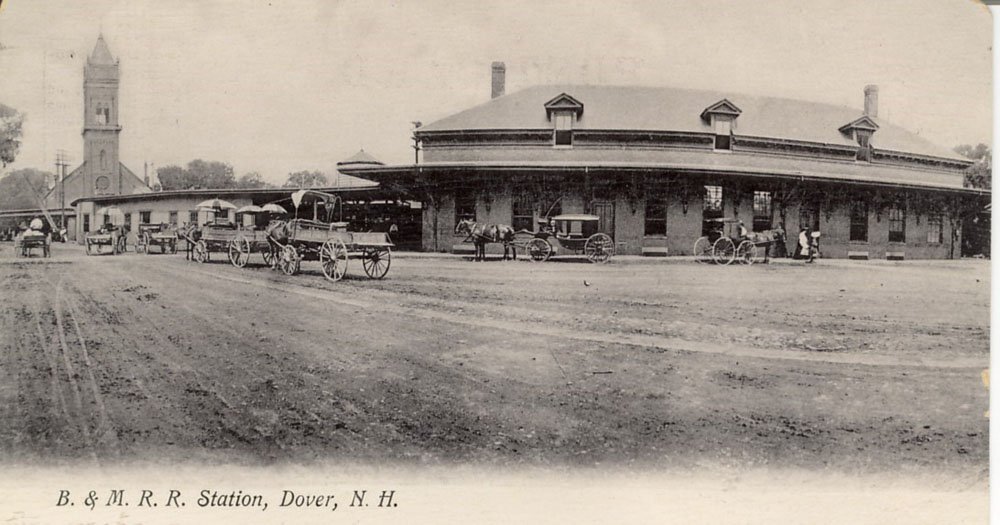

Over the course of the next year, work continued to get through Coffins Cut, which meant burrowing through a hill. Finally, the track was extended into town, so a new railroad station was built on land once used by the Cochecho Manufacturing Company as a wood yard, extending from Third to Fourth Street and surrounded by a wood fence. The new station (now the site of the Municipal Parking Lot) was built of wood, with pillars in front, and was painted dark gray, then sanded. It stood over the track, and the train cars went through it via large doors at either end. In the winter, the doors were open only to let trains pass through; however, this practice was soon stopped because the smoke from the wood smoke of the engines was stifling. This station was replaced in 1873 by a brick station constructed on the same site. It was a two-story building that did not cross the track.

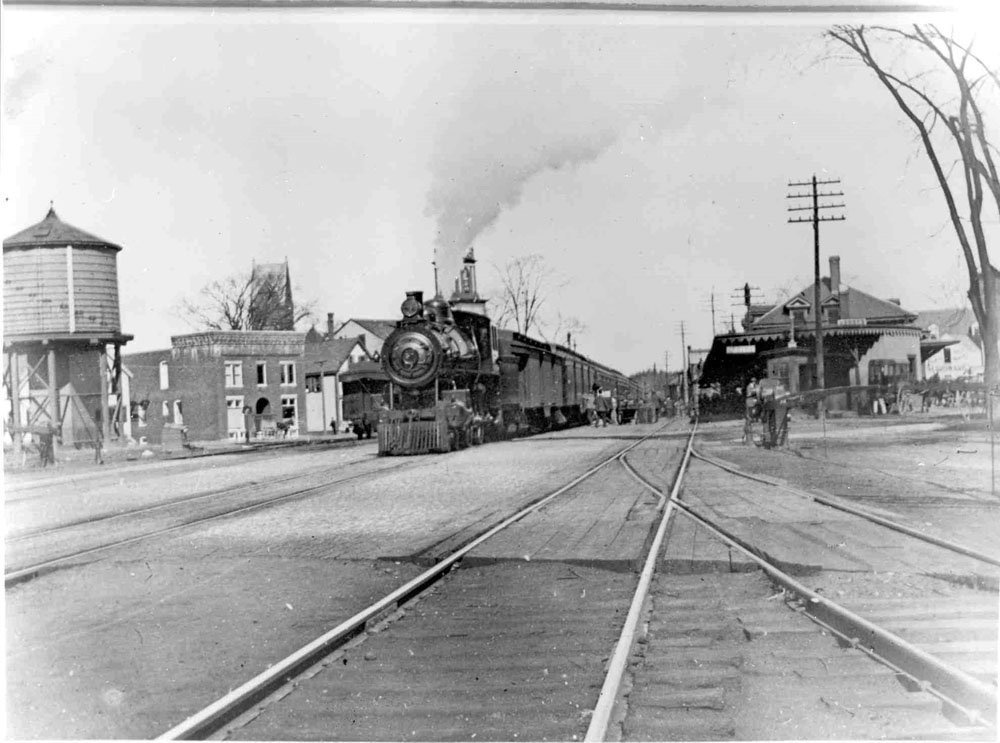

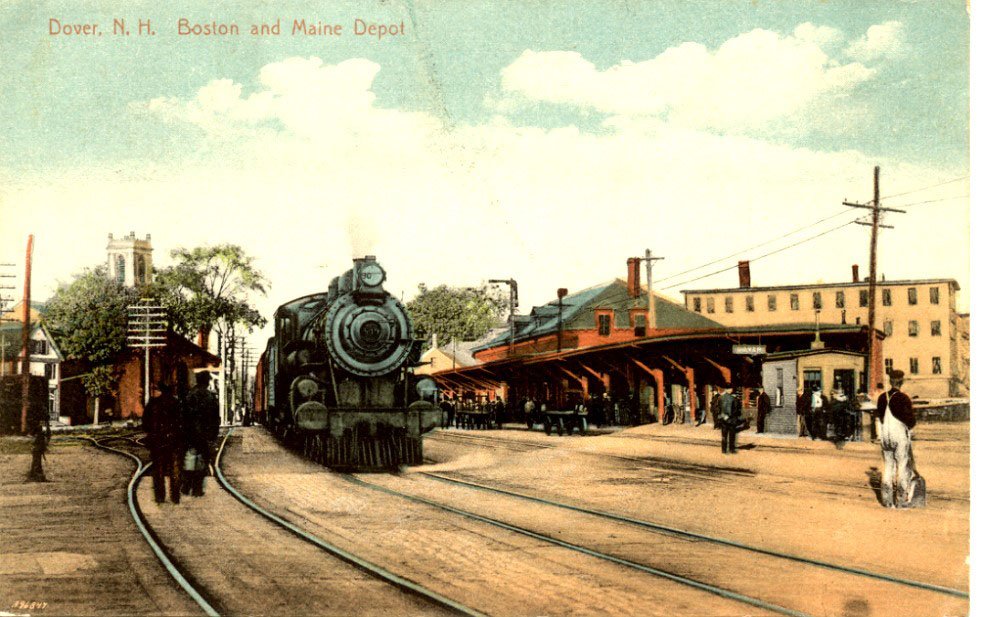

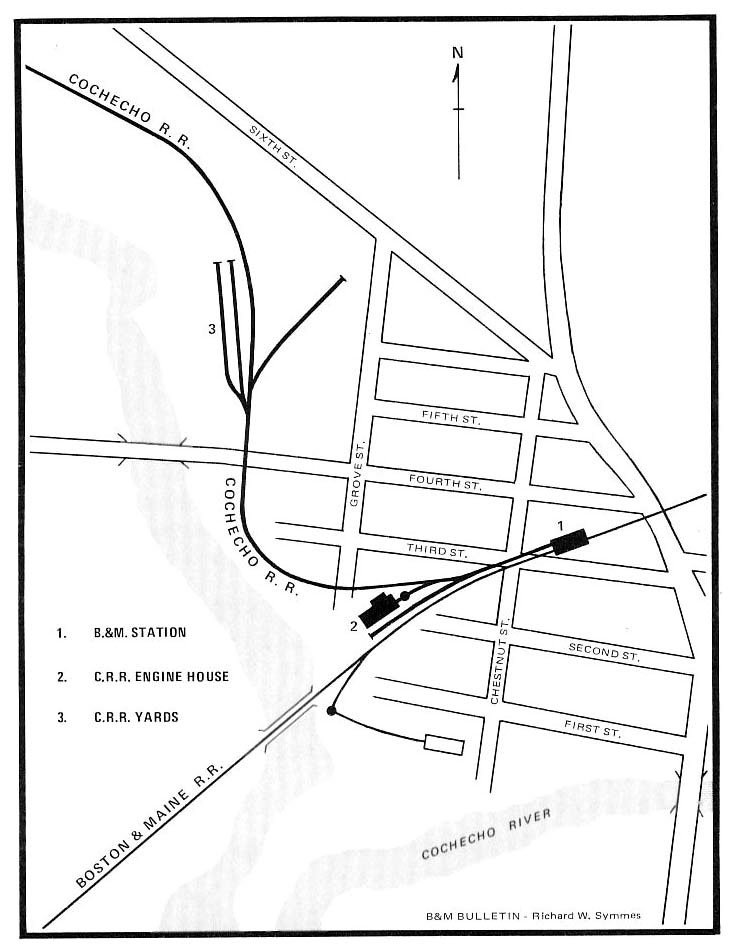

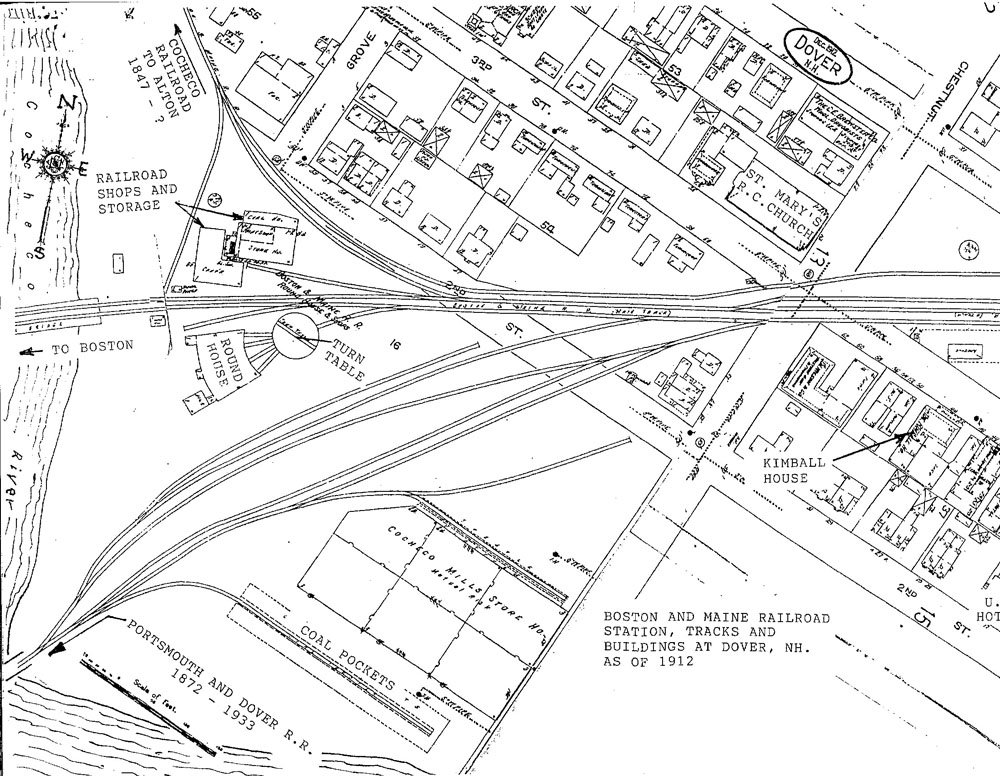

The railroad was an important part of Dover through the next fifty years. The railroad bridge on Broadway was rebuilt in 1883 (and again in the mid-1920’s) as train traffic increased. On Washington Street, the first arch had been designed for a single track, but by 1899, it was torn down and rebuilt for a double track. By 1900, the train yard covered all of the land from Chestnut Street and Third Street to the Cocheco River. By 1910, sixty trains a day stopped in Dover, with names like the “Cannon Ball,” which left Boston at 8:00 a.m., arrived in Dover at 9:52 a.m., and went on to Portland, arriving at 11:05 a.m. The Boston and Maine moved their Easter Division headquarters to Dover from Sanbornville in 1911, after a disastrous fire destroyed its facility there on April 8. A new engine house, six-pit brick roundhouse, and roundtable were built off Oak Street in 1919.

The Portland Division was consolidated to Dover from Boston, and Salem, Massachusetts, in 1928, requiring a third story addition to the downtown station, where operations were centered. In 1946, the train yard included two water tanks which were filled with Cocheco River water pumped electrically by the Train Director at the Dover Tower. In 1952, diesel replaced steam in train engines. But with the rise in popularity of the automobile and the airplane, trains began to lose favor. In the last few years before passenger serviced stopped in Dover, passengers were transported in what were known as Budd cars, or Buddliners, because they were manufactured by the Budd Manufacturing Co. The Budd cars were diesel-electric, and did not use a locomotive. The diesel engine and generator were located under the floor of the car. These were run generally as single car trains, but it was possible to have longer trains.

When passenger service was discontinued on June 30, 1967, the downtown station was demolished and a new smaller station was built in the old Second Street railyards west of Chestnut Street. That station was demolished when the existing station was built for the renewal of passenger service in 2001.

In the intervening years, freight continued to be carried over the Portland to Boston line, and gravel was transported from Ossipee to Boston over a former Eastern RR line. Finally, on December 14, 2001, passenger service from Portland to Boston, stopping in Dover, resumed with the arrival of Amtrak’s “The Downeaster,” bringing full circle the story of the railroad in Dover.

OTHER RAILROADS IN DOVER

There were three separate railroad companies with lines running through Dover, but two eventually merged with the third, the B & M Railroad. The Cochecho Railroad, later called the Dover & Winnipesseogee Railroad, ran forty-four miles from Dover to Alton Bay, reaching there in 1851. This line had one station in Dover, the Cocheco station, about four miles from the Dover Station in the northern end of Dover where the railroad crossed County Farm Cross Road. The line was absorbed by the B & M in 1863; passenger service ended in 1935.

Work on the Dover and Portsmouth Railroad was begun when ground was broken on November 25, 1872 in back of the old Dover jail on Silver Street. The line ran from the Dover station across the river, and on to Portsmouth via Dover Point. The first stop was at the intersection of Folsom and Washington Street. It then went by the old jail, and stopped at stations more or less equally spaced called Sawyer (now Agway), Cemetery, Cushings, Bellamy, Hilton, and Dover Point. Four trains went back and forth daily on the line. The B & M took over this line in 1884. Passenger and freight service ended in January 1935.

HOW THE SYSTEM WORKED

Telegraph – One of the major advances in railroading was the invention of the telegraph. Before the telegraph there was no way for a station master to know where the trains were. If a train was supposed to arrive at 5:30 and it had not shown up by 5:45, the people at the station had no way of knowing why the train was late or where it was. After the telegraph came into use in 1851, the number of accidents on rail lines dropped dramatically. After that, telegraph lines were constructed alongside all railroad tracks.

Gate Tenders – Due to cost factors, it was not practical to have an overpass or underpass every time the railroad crossed a street, so some of the streets were crossed at grade level. At each grade crossing it was necessary to have some way to control traffic on the street so this traffic would not be hit by a train. In the beginning these crossings were controlled by crossing guards who stood in the road and stopped the traffic. As automobile traffic got heavier and faster, this method of traffic control became more dangerous. Gates were developed that could be raised and lowered by the crossing guard (now called a gate tender) so that he did not have to stand in the road and risk being hit by a truck. After dark the gate tender would have to hang his lantern on the gate to be sure the oncoming traffic would realize that the gate was down.

There were eleven grade crossings in Dover: on the B & M Line (Main Line) at Chestnut Street and Central Avenue; on the Cochecho Railroad at Fourth Street; Whittier Street, Watson Road, County Farm Road, and County Farm Cross Road; and on the Portsmouth & Dover Railroad at Washington Street, Folsom Street, Fisher Street, and Central Avenue. When the train was about to go under an overpass that didn’t have much clearance, there would be a wire stretched across the tracks with strips hanging down to warn anyone who was on top of the train to get down so they would not splashed against the overpass.

Transmitting information Down the Line – Rail was used because there is less friction between the wheels and the rails, so that heavy loads can be carried using less motive power. One of the drawbacks of this is that it takes longer to get up to speed and also requires a longer distance to stop. It also constrains the train to the track, so that the only control the engineer has is the ability to control speed. In order to know when to speed up or to slow down, the engineer needs to have information about the condition of the track and where other trains are located. In the early days of railroads the engineer had no way to get this information so he had to depend on people along the tracks to tell him what to do.

In order to get information to the engineer, a system was developed which required people to be stationed at certain points along the track who passed information from one to the other by use of visible signals. This information was transmitted to the engineer in the same manner. Each point had to handle two signals, one for eastbound trains and one for westbound. The information on eastbound trains was transmitted to the next point to the east, and the information on westbound trains was transmitted to the next point west. The stations had to be close enough to each other so that the signalman could see the next point, either by naked eye or by the use of a spyglass.

The first system that was used consisted of colored balls that were raised and lowered by the use of ropes and pulleys. After dark, a lantern was attached to the ball so it could be seen. The information that was transmitted depended on the height of the ball. When the ball was up high, the train could operate at maximum speed. This is where the term “highball” came from. Next came the semaphore system, which transmitted information based on the angle of a flag mounted on a pole. Later, openings were made in the signal arm which had colored inserts, which would change the color of a light shining through them depending on the angle of the flag. The colors were red, amber, and green, the same as our present day automobile traffic signals.

After the invention of the telegraph in 1851, the same information could be transmitted by telegraph wires between stations, so that one station did not have to be visible from the next. However, the same semaphore flags had to be used to transmit the information to the engineer. In 1907, the telephone came into use as a method of communication between stations.

Communication on the Train – It is said that the first non-verbal communication between the conductor and the engineer on a railroad train happened when a conductor ran a cord along the cars and into the cab of the locomotive. He tied a block of wood on the end in the cab, and when he wanted to train to stop, he would use the cord to “jiggle” the block of wood. Later, the block of wood was replaced with a bell and even later, the whole system was electrified and the electric bell was controlled by a push button.

TRAIN PERSONNEL

Engineer – The engineer sits in the cab and runs the engine. He has to have good eyesight and steady nerves as he is on constant watch to be sure the track is clear. He had to know all the procedural rules and signal meanings, and sounds a whistle when approaching a crossing.

Conductor – The conductor is in charge of the train movement. He ensures that the correct “markers” or “signals” are displayed and that each crewmember carries out assigned responsibilities and duties. He is responsible for collecting tickets, fares and calling out stations.

Fireman – The fireman was responsible for keeping the fires going to produce the steam to power the train. He shoveled wood or coal into the boiler to ensure a steady heat was produced to create the steam. Firemen always had 2 shovels with them because it was not uncommon for one shovel to get burned in the fire.

Dining & Kitchen Cars – Steward is in charge of Dining Car and ushers passengers to tables. Waiters take orders and deliver food from the kitchen. The kitchen car is staffed by a chef and several assistants to prepare the meals.

Baggage Agent – Checks the baggage in the station.

Porter – Helps with bags at the station.

Baggage Men – Stores and looks after the baggage on the train.

Roundhouse and Railroad Shop Workers – The roundhouse was used for cleaning and light repairs. The “railroad shop” was used for major repairs. Skilled mechanics, machinists, blacksmiths, boilermakers, crane operators, electric drill operators, lathe operators, pattern makers, welders, riveters, electricians, inspectors, metalworkers, painters and laborers were employed to maintain the railroad cars.

Car Inspector – Key role in the safety of the railroad cars. They inspected both passenger and freight cars to ensure extensive safety and mechanical criteria were met to avoid accidents and delays.

Track Crews – (Railroad track, etc.) Tracks, bridges, trestles, tunnels, telephone and telegraph wires and signals.

THE RAILROAD AND THIRD STREET BUSINESESS

Before the arrival of the Boston and Maine railroad into downtown Dover in 1842, the Third Street are was strictly non-commercial. A few tenements and boarding houses dotted the south side of the street and the north side contained only the huge wood yard owned by the Cocheco Manufacturing Company who used vast lots of timber in their factory boilers.

One of the few structures on Third Street at this time was a small wooden church constructed in 1827 for $2500 by the First Universalist Society. Located at 40-44 Third Street, it was enlarged in 1847 to accommodate a growing congregation. In 1875, church fathers sold the building to George G. Lowell for $5000. Lowell added a three-story brick front and converted the upper floors to a hall in 1880. The structure was renamed Lowell’s Block. At street level, his son John opened a grocery and crockery shop in 1886 and many civic and fraternal organizations made use of the large meeting space upstairs, grandly called “Lowell’s Opera House.” In 1912, this building was renovated and became the Lyric Theatre for the next twenty years. In 1933, the Dover Distributing Company (later known as The Decorating Center) opened here selling paints and wallpaper for nearly the next half century, closing in 1982 after a fire.

Back in the mid-1840s, with three daily trips to Boston and two to Portland, the railroad slowly began to generate some business activity. The Eagle Hotel on Franklin Square served as a “general railroad and stage office” and two express companies, Niles and Whidden’s, opened on Third Street. During the 1850s, a small railroad depot was constructed on the site of the factory wood yard (the mills were now using coal as fuel) and a third rail express company set up shop. By 1859, two small hotels, the Franklin House and the City Hotel (later called Watson’s) opened as well. Third Street also became the center of Dover’s newest industry, shoe manufacturing, with two small factories at its west end and seven more on nearby Chestnut, Fourth, and Grove Streets.

The 1860s saw the emergence of small stores catering to travelers’ needs. Grocers, confectioners, dry goods shops, tobacconists, and several restaurants, saloons and pool halls opened. In addition, several retail shoe stores sold locally-made boots and brogans at bargain prices. As railroad traffic increased and commerce grew, Third Street broadened its appeal as well. Several “hairdressers” (not called “barbers” until the 1920s) flourished beginning in the 1870s as did a few tailors and Chinese-owned laundries. More specialized markets selling fish, meats, fruits, liquor, ale, patent medicine, and second-hand furniture added to the mix of businesses.

Two new large hotels opened: the Kimball House in 1871 at 48 Third Street and the United States Hotel in 1876 at 18-20 Third. The original, but now outclassed, Franklin Hotel was between them at #38. A new brick railroad passenger station was completed in 1874 with a waiting room, toilets, offices, newsstand, dining room/café, baggage room, and a projecting roof to help protect travelers from inclement weather.

The Kimball House became a Third Street fixture for over 100 years until, as the Hotel Kimball, it succumbed to a fire in 1982. In 1889, it advertised a major renovation: “Refitted and reopened with an attractive appearance for the wayfaring man.” In 1891 it was promoted as “first class in every respect.” In 1905 it was “a pleasant retreat for commercial travelers” with steam heat, electric bells, and sample rooms for salesmen to showcase their wares to customers. Amenities also included a pay telephone (one of only thirteen in Dover at the time!). By 1912, the Kimball not only had phones in each room but delivered “hot and cold water in all rooms” for only $2.50 to $3.00 per night. In 1921, another renovation boasted, “25 new rooms just completed: the only hotel in the city with a private shower and tub baths.” In the 1930s the Kimball was described as “the traveling man’s home.”

The United State Hotel, demolished in 1919 to build the present Strand Theatre, was owned and operated by John W. Ricker for its first thirty years and had a hack and livery stable adjacent. Ricker lived in rooms above the hotel for all that time and was always on call. Although the U.S. Hotel was less flashy, it was a lively competitor with the Kimball for travelers’ stays. Among the patrons listed in the hotel register were Buffalo Bill Cody and John Jacob Astor.

The Franklin Hotel at 38 Third Street, although oldest, had the most unstable history. No owner could seem to be able to make a go of it for very long. Despite many name changes designed to give it some cache, it remained essentially a boarding house, just as its 1874 ad proclaimed: “transient and permanent boarders accommodated on reasonable terms.” At various times it was known as the New England House (1876), New Hampshire House (1887), Evans House (1890), The Anderson (1900), The Lenox (1905), Grand Union (1912), Strafford Inn (1917), and City Hotel (1920) before it was converted into Elias Anton’s Furniture Store ca. 1921. Anton’s was succeeded by Ross Furniture, owned by R. Ross Payeur, in 1948.

There was one other well-known hotel on Third Street: the Leighton at #13. George Leighton began his business there as a barber in the early 1900s, soon added a café called the National, and by 1905 was advertising rooms-to-let. By 1920, the Hotel Leighton was famous for its dining, particularly its $1.00 Thanksgiving dinner and its “homelike catering served daily to ladies and gents.” Mr. Leighton owned the hotel until about 1948. It was then operated as Anton’s Hotel by Mrs. Teresa Anton until its closure in 1962.

Adding to the bustle on Third Street in the 1920s was the popular 1,000 seat Strand Theatre which opened on September 22, 1919 with Mary Pickford starring in “Daddy Long Legs.” Movie prices were $.11 and $.17 for a matinee and $.17, $.22 or $.28 for an evening show. The Strand also held the world premiere of “The McConnell Story” featuring the exploits of Dover’s own Korean War flying ace, Captain Joseph McConnell Jr. This film premiered here on August 15, 1955 and starred Alan Ladd and June Allyson.

Another long-standing Dover business was begun on Third Street by A.N. Ward in 1884. Mr. Ward was a “practical embalmer” who advertised his “first class carriages and hearses.” He was bought out in 1897 but two men, Harry B. Tasker and T. Jewett Chesley who lived over the store and promised “all orders promptly executed”! The Tasker and Chesley Funeral Home stayed at this 12-14 Third Street location until 1968 and continues today as the Tasker Funeral Home at their Central Avenue location.

By the turn of the twentieth century, many of the smaller-volume shoe manufacturing companies had closed in this vicinity, leaving several small vacant factories neighboring the railroad depot. These buildings’ locations, so convenient to a freight stop, were ideal for four types of businesses which grew to fill all empty warehouses and mill spaces in the Third Street area.

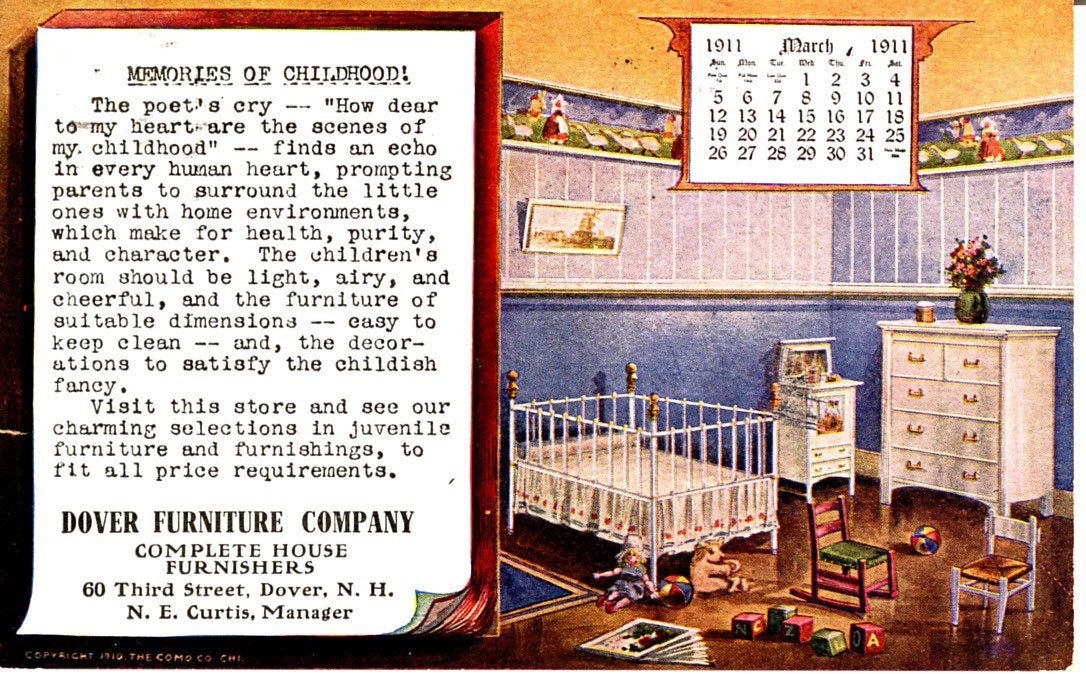

The first was furniture. In 1895, J. Everett Ewer and J. Eugene Mooney opened the Dover Furniture Company in one-half of Charles Clement’s abandoned shoe factory near the corner of Chestnut Street at 60 Third Street. This store, “the largest complete house furnishers in New Hampshire,” promised “artistic furniture at the lowest prices” on four floors of merchandise encompassing 16,000 square feet of showroom space. This store was succeeded, in 1920, by the E. Morrill Furniture Company for the next twenty years, then followed by Greenlaw’s Furniture from 1940-48, and finally by Warren’s Furniture until 1977 when the building was burned by an arsonist. With Anton’s/Ross’s just down the street, Third Street became Dover’s furniture district.

The second re-use of the old factories was by bottling companies and wholesale liquor dealers. There were eight saloons on Third Street in 1900 and clever entrepreneurs arose to provide the refreshments these bars consumed. The oldest company in the area was begun in 1884 by Reuben G. and Henry G. Hayes on Fourth Street. They bottled beer, cider, and ginger ale and moved by 1900 to 23-25 Chestnut Street. By 1905, the brothers had sold the company and it became known as the Dover Bottling Company and expanded the product line to include tonics and soda water. The other bottler in 1900 was Mallen and Loughlin at 50 Third Street. These two partners, both named Patrick, were agents for the Eldredge Brewing Company and specialized in lager beers, ales, porters, and “pure Kentucky whiskey” for “family and medicinal purposes.” By 1912, Patrick Loughlin was the sole owner of this business and by 1917 it was owned by Bernard Loughlin. A branch of the Rochester Bottling Company opened at 40 Third Street just after the turn of the century, as did the Frank Cunningham Company at 44 Third. Cunningham was the exclusive Dover dealer for “Frank Jones’ celebrated ales and porters and Narragansett lager” and later sold the business to James F. Dennis around 1910. After Prohibition began in the fall of 1919, all of these companies closed up shop.

The third industry accommodated in the factories were wholesale meat dealers. The earliest began on Second Street in 1884 and its three founders, J. Henry Wheeler, S.E. Hyde, and T.H. Wheeler incorporated as the Dover Beef Company in 1887. By the turn of the century they had expanded to a processing plant at 11-13 Fourth Street and sold “Hammond’s Dressed Beef and Provisions”. In 1921, they became Swift and Company and stayed at that location until 1970 when they moved out to an industrial park off Knox Marsh Road. The company was last known as Mapelli Food Distributors in 1998. A second important Dover meat firm, the J.M. Wilson Company, was located in 1900, at 62-64 Third Street in the other half of Clement’s old shoe factory. It had begun operations in 1888 as the East St. Louis Dressed Beef Company and was run by Charles and Arthur Morrison. Wilson’s became known as The Armour Company ca. 1943 and provided beef, mutton, pork, lard, ham, and tripe to local markets and restaurants. They discontinued operations in the mid-1950s.

The fourth industry in the area was bakeries. The Brown-Beckwith Company at the corner of Grove and Third Street provided “So-Fine” cakes and doughnuts, while the National Biscuit Company (Nabisco) had a warehouse facility at the corner of Grove and Chestnut in the 1920s. Perhaps the best-known of the Dover bakeries was the M & M Bakery owned by Patrick H. McManus. M & M built a factory on Third Street (now Foodees Pizza) in 1927 when their business expanded from Central Avenue. While their retail bakery remained on Central Avenue, their baking ovens and mixing rooms moved here. M & M was famous for its Big Butter Krust loaf which was delivered daily all over New England by a large fleet of M & M trucks. This popular bakery closed in 1961.

During the early years of the twentieth century, there were 24 passenger trains arriving and departing Dover daily. In 1913, B&M managers had to order the half-dozen or so hot dog vendors, in competition with each other, to keep off the premises at the depot. Taxi services and trucking express companies had replaced the hack and livery stables of the past.

Progress had made Third Street area more transient and soon, more run down. A series of fires further changed the old neighborhood. Ironically, all these major conflagrations occurred in January: the Morrill Block fire in 1932, which destroyed 26 businesses at the street’s Central Avenue end; the Warren’s Furniture fire in 1977; and the Kimball blaze in 1982. Consequently, today we can only observe the newer buildings that have replaced those that burned: the renovated Morrill Block, Varney’s Cleaners/Laundromat, and the Asia Restaurant.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.