Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

2003 Heritage Walking Tour

Heritage Walking Tour Booklet September 28, 2003 by the Dover Historical, Dover, NH, c. 2003.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

The Cochecho River

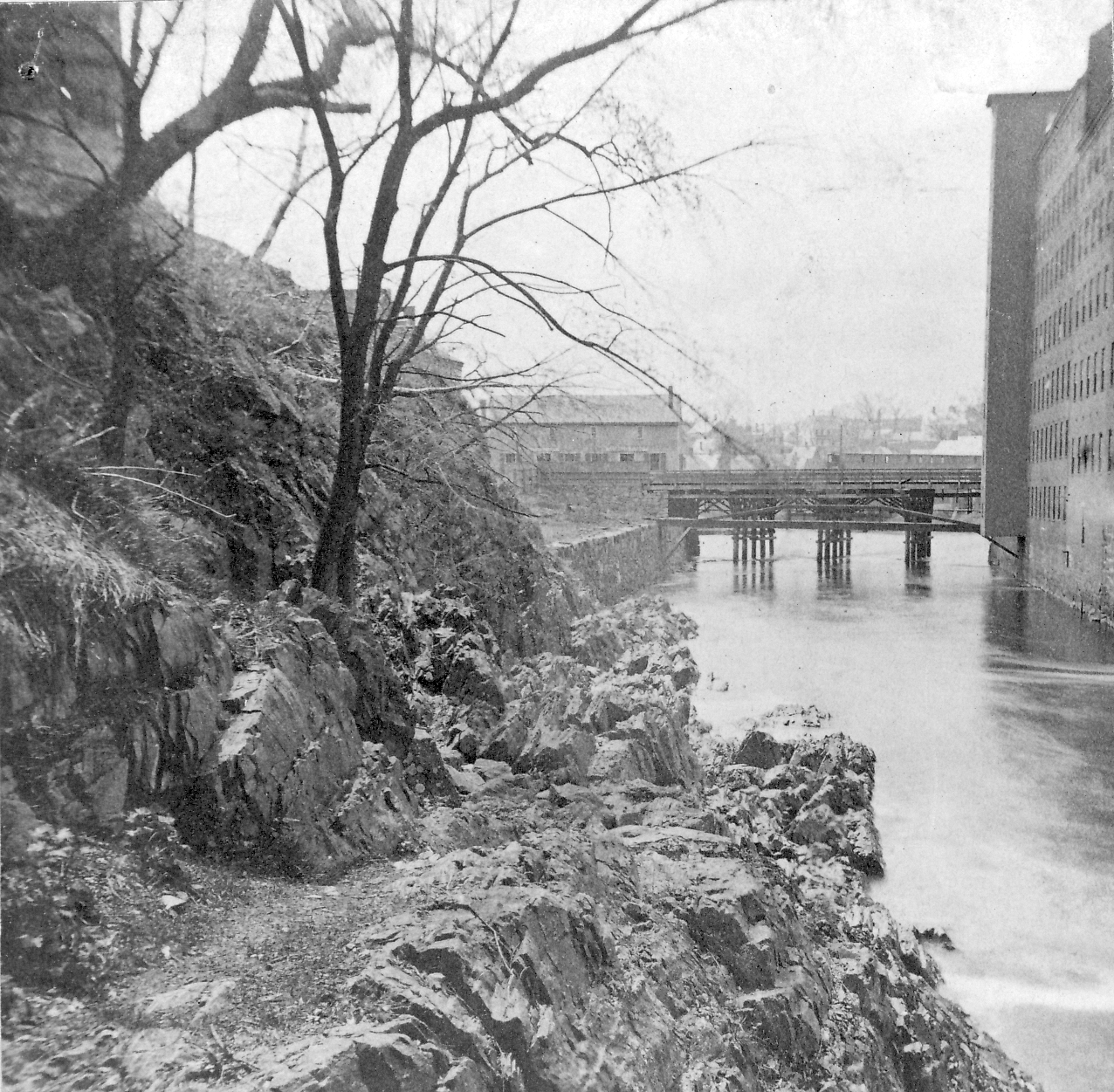

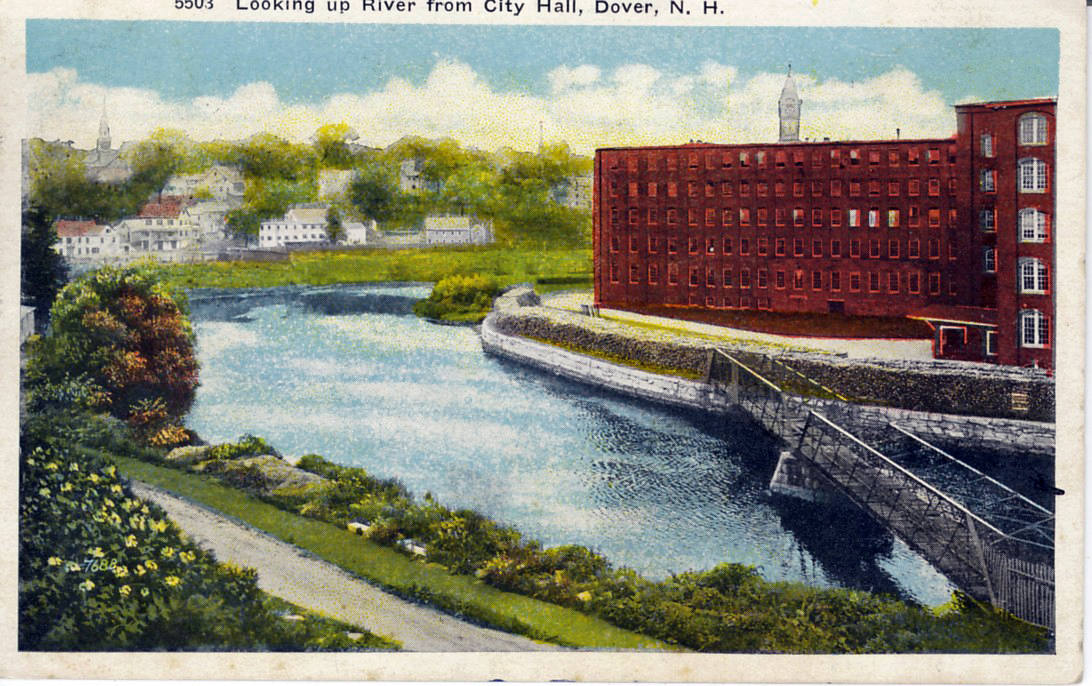

COCHECHO RIVER

The word “Cochecho” is a Native American word meaning “swift, foaming water”. Since the 19th century, it has been spelled two ways in local use. The traditional spelling, Cochecho, was altered in 1827 when the cotton mill owners registered their new company name in Concord. Through a spelling error made by a clerk in the Secretary of State’s office, the business was officially registered as the “Cocheco” Manufacturing Company, minus the final “h”. Since that time, the word has been spelled both ways. Purists use the original spelling to refer to the founders’ settlement, the river and the adjacent street, but choose the alternate spelling, Cocheco, when citing the mill and its properties.

Dover has 50 miles of river frontage along the Cochecho, Bellamy, and Piscataqua Rivers. And while seven miles of the Cochecho River are in Dover, its headwaters actually begin 42 miles upstream on Birch Ridge in New Durham. The river touches nine other towns and cities and falls 900 feet in elevation before it reaches Dover, where it becomes a tidal river below the Lower Falls dam. Its watershed drains an area of 185 square miles and there are some 16 lakes and ponds which connect with it. The water quality of the river is currently Class B (Fishable/Swimmable) with some Class A tributaries like the Isinglass River. Below the falls in Dover, the Cochecho River is still some three miles from the sea. A bit further out, it joins with the Salmon Falls River before merging into the Piscataqua and the saltwater Great Bay. In some places close to Dover Landing, the depth of the river’s channel is only three feet at low tide.

COCHECHO RIVER SHIPPING, 1650-1842

The Piscataqua gundalow was an indigenous watercraft in use here by the mid-17th century. The flat-bottomed, square-ended boat was 20-30 feet long, usually manned by a crew of two or three with very long poles for steering. It had no deck except for small platforms at either end on which to stand and navigate. Cargo was carried in the open middle of the vessel and the gundalow’s capacity could approach up to 35 tons of cordwood, grass, hay, or bales of cotton. Even fully loaded, the gundalow could come up to Dover Landing docks at half-tide.

They were largely dependent on the winds and tides for movement, but drew only two feet of water. In Dover, these workhorses of the tidal river could visit the Nail Factory’s dock in the 1820s, bringing iron and taking away finished nails.

The gundalows were also able to tie up next to larger ships that could not come all the way up to Dover’s docks because of the shallow channels. They would offload cargo in a process called “lightering”. Although it was quite efficient, it did add another step and additional expenses to delivering goods to Dover.

Later gundalow models were designed with a spoon bow and stern, a lee board on the port side, and a cabin aft. A “lateen” triangular sail was attached to a short 10-15 foot mast and there was a yard arm as long as the vessel itself. The boat was not pretty, but by 1810, there were ten gundalows in constant use between Dover and Portsmouth, transporting 30,000 tons of cargo annually.

In the 1820s, packets came into use. “Packet” was a catch-all term used for any vessel that was not a gundalow or a full-sized schooner. They were also called “sloops” or “coasters” and were generally 30-40 feet long. These boats could only reach Dover at high tide as they drew 7-8 feet of water. They ran regular schedules to Boston and Portland and there were even two daily passenger service packets to Portsmouth. There were over a dozen packet captains in Dover, operating independently until 1835 when word was received that Boston & Maine railroad had been chartered for a route through Dover. In order to compete with this new mode of transportation that threatened their livelihood, these captains formed The Dover Despatch Line of Packets and boasted that their lines were faster, safer, and cheaper! By 1838, the number of packets in Boston from Dover was 97, more than any other place except Portland.

As Dover’s reputation grew as “the greatest shipping center in the state”, larger and larger vessels arrived as near the port as they could, perhaps a mile or two away from Dover wharves, still having to be “lightered” by the smaller gundalows and packets. In 1840, nearly 200 large ships brought materials to Dover, cargo valued at $750,000. Many of these schooners arrived from the South, bringing raw cotton for the mills, then taking the finished bolts of cloth out. Others delivered tons of coal for the Cocheco Manufacturing Company’s boilers.

By 1842, the value of goods transported on the Cochecho River was $2.4 million. Steamers, tugs, and excursion boats also offered passengers “ample accommodation and polite attention” on daytrips to the Isles of Shoals. But 1842 was also the year that the new B&M railroad arrived. The traveler and businessman then had a dilemma: rail was more expensive but more reliable, not dependent on weather and tides. River transport took a more direct route and was less costly, but schedules were uncertain. For the next couple of decades, the rails won out and shipping declined on the Cochecho River.

DOVER LANDING

In 1767, Dover’s population was 1,614. Washington Street was a gully, a path for Coffin’s Brook which descended from Arch Street. Dover’s landing was just a storage area for cordwood and hay bales. Its riverbanks had no real wharves or commercial docks. Just after the Revolutionary War, this area began to develop. For people upcountry and inland, Dover was the nearest tidal port to trade and export their homegrown goods.

In 1785, selectmen voted to lay out a road, four rods wide, and sell or lease lots at The Landing. Money raised was used for schools, a town bell, and a new courthouse. In 1802, the town constructed a slaughterhouse there, preferring that to the previous practice of killing hogs right in the middle of the square! The first brick block of stores was built at Dover Landing by Joseph Smith and Rogers & Patten in 1815. More streets were laid out in the area and soon, businesses and residences closely packed Linton’s Lane and Water, Young, Perkins and Belknap Streets. The Landing was a rough-and-tumble place, busy with auctions and bartering, mongrel dogs, large rats, and the occasional cockfight. But soon, the teams of horses bringing items to the wharves were lining up all the way back to Garrison Hill!

In 1794, Joseph Smith opened his bakery there, with its brick ovens close to the water so the smell of fresh-baked bread wafted over the boats. William Hale opened a general store and Nathaniel Ela opened his tavern. Enoch Nutter’s Clock shop followed by 1800, along with the offices of The Dover Sun, a school, a distillery, a tannery and a dram-shop. Coopers and blacksmiths were abundant.

In 1825, Hosea Sawyer built his brick block at the corner of Main and Portland Streets, facing the newly-named Lafayette Square. The building cost $8,766.26 and, with its graceful curved front, was a showpiece of the town.

In a 4th of July speech in 1826, former citizen John Mellen expounded: “…How changed the scene! Your commerce and boat navigation has greatly increased and…the number of your merchants is now forty-one and their stock not less than $106,000. The number of mechanicks…in good employment is not less than 400. The amount employed in your manufactories…affords a source of employment to more than 2000 persons…”

In 1838, the third block of brick stores, owned by Nutter and Pierce, was constructed at the corner of Washington and Main Streets. Dr. Timothy Dwight of Yale, who had visited Dover in 1796 and called it “a declivity…with nothing sprightly…in the town”, returned some years later and noted Dover was “considerably improved since my last visit.” Dover’s population had almost doubled in the decade between 1820 and 1830 and its citizens, now numbering nearly 6500 in 1840, were middle-class consumers with a demand for finished goods and the so-called niceties of life. They could find nearly everything coming through The Landing.

SHIPBUILDING 1650-1838

Major Richard Waldron commissioned the construction of a frigate in Dover in 1650 to protect the local merchant trade from the coastal pirates who routinely interrupted their ventures abroad. This was the first recorded instance of any shipbuilding industry in Dover. In 1661, a naval vessel was built for the British government. By 1671, Dover was exporting one million pounds of fish to Europe, lumber and barrels to the West Indies and Barbados, masts and pelts to England, and salted cod, barrel staves, clapboards and kegs to the southern colonies.

The combination of a navigable river with an outlet to the sea, an abundant supply of timber, a source of water power to run the sawmills, and the presence of good carpenters resulted in Dover’s development as one of the largest boat-building areas in New England. As timber stocks lessened, logging moved inland. This led to a plan, in 1792, to construct a canal from Dover all the way to Lake Winnipesaukee. Obviously, this never materialized, but the idea was still being bandied about as late as 1824.

By the 1820s, several Dover shipyards were flourishing, building a least a half dozen vessels a year, ranging from 30 to 600 tons. Most of the resident packet boats and coasters were built locally, to the exact specifications of their captains who knew the quirks of the seacoast’s waterways. Two of the better-known shipbuilding facilities were Samuel and William Hale’s boatyard at Squall Point (now Henry Law Park) where the 250-ton sister ships, the Lydia and the Martha were built, and John Saville’s boatyard at “The Beach” (now the rear of One Washington Center) where two schooners, the Charles Henry and the Ellen and Clara were constructed for trade with Texas. The last ship built in Dover belonged to Captain Robert Rogers who set sail on the 600-ton Orinoco in September 1838. The vessel was unfortunately lost at sea one year later.

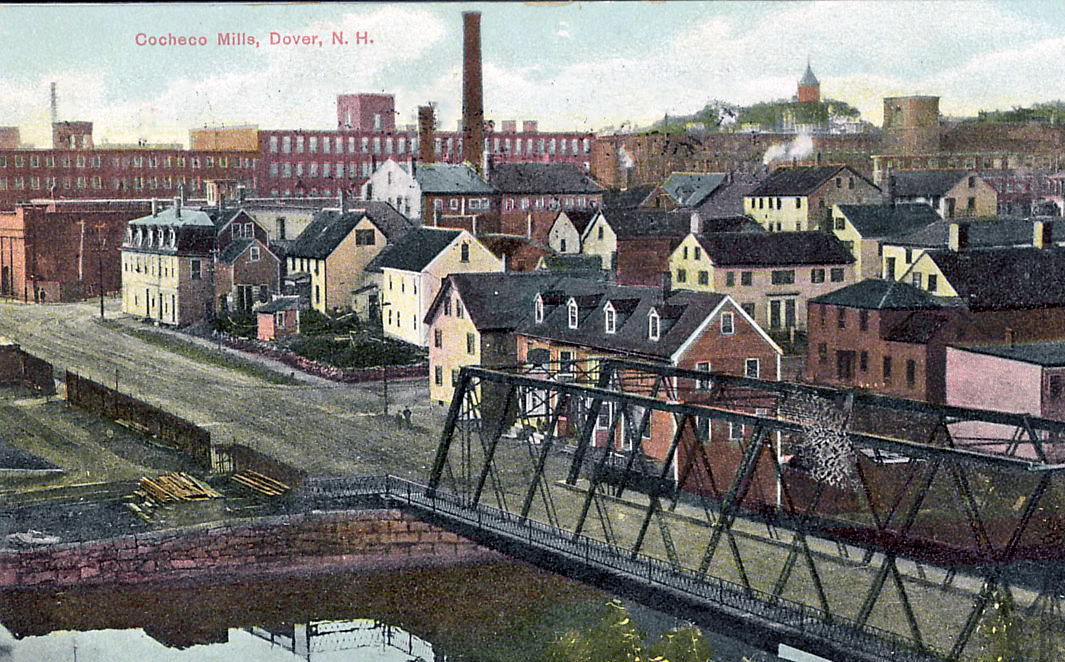

LOWER WASHINGTON STREET BRIDGE SITE AND FOOTBRIDGE

The original steel bridge at this location was built in 1896 and was a single-span, double intersection Warren truss by the Boston Bridge Works. It was closed to vehicular traffic in 1966 due to its unsafe, rusted condition. In 1977, it was closed even to pedestrians. In 1980, the City of Dover prepared plans to replace the bridge with a 2-lane, 32 foot wide structure but ran into difficulties with the state’s Historic Preservation Office who deemed the bridge eligible for the National Register of Historic Places because of its unique antique design.

On August 19, 1981, the arguments turned moot as a large girder on the bridge collapsed, taking down several paper-thin beams with it. Unsalvageable, the bridge was eventually torn down. In 1996, a new covered footbridge was constructed on the site. It opened for pedestrian traffic on June 4 and was dedicated on July 26. Its 155-foot span cost $195,000, with a coastal grant picking up $55,000 of that cost.

DOVER’S SEA CAPTAINS

During the 18th and 19th centuries, over one dozen deepwater sea captains made Dover their home. These were not the commanders of local packets and gundalows, these were the “big boys”, the ones who voyaged to China, North Africa, Singapore, Brazil, Amsterdam, the Suez Canal, Chile, the Philippines and Hawaii. Their trips might take them away from home for a year or two at a time. When they were at home, most lived in the Portland and Rogers Streets neighborhood, in view of the Cochecho River. Dover’s local newspapers took care to follow their journeys and report on their arrivals and departures from foreign ports of call. Many spent nearly 50 years at sea and one captain reported that he did not see his baby daughter until she was 13 months old! They survived shipwrecks, fires, Algerian prisons, blackmail and ransom attempts, Confederate attacks, crew mutinies, political uprisings in faraway ports, pirates, and of course, plenty of fog, rain, hail, snow, lightning, hurricanes, monsoons and tidal waves.

Surprisingly, many of the sea captains had wives who accompanied their husbands on their journeys. The Woodman Institute Museum in Dover has several treasures on display which were acquired by these sea captains or their wives as they sailed the globe. For more detailed information about the buildings surrounding “The Landing” area, please refer to the 1994 Dover Heritage Walk brochure.

DREDGING THE COCHECHO

Skippers on Dover’s Cochecho River had always known that navigating could be treacherous. The channel leading to the port and the wharves was narrow and shallow, even at high tide. At low tide, only the smallest crafts could make it all the way. When local businessmen studied development at The Landing, there was only conclusion: we’re busy now, but we could be even more successful if the river was deeper. Town officials applied for federal money to dredge portions of the Cochecho River at its narrowest places. $5,000 was granted in 1835 and $5,000 more in 1837. After that effort, nothing was done for more than three decades.

In 1871, Congress accepted a petition from Dover’s Board of Trade, which was made up, not surprisingly, of gentlemen with businesses on Cochecho Street: Mayor Stevens (of Wiggin & Stevens), John Bracewell (of the Dover Navigation Company), Moses Page (of C.H. Trickey’s), and A.C. Chesley (of Converse & Hammond). With the help of local congressman J.H. Ela, $10,000 in federal dredging funds were approved for Dover. Over the rest of that decade, dredging work continued with five other federal appropriations totaling $63,000.

In 1880, the Dover Enquirer commented that “there were nine schooners moored at one time in the lower Cochecho recently. A grand sight, prophetic of the brilliant future awaiting Dover as a port of entry.” During the 80’s, an additional $67,000 was received and the Enquirer teased its rival port: “Our Portsmouth friends appear to be frightened: Don’t be alarmed good people, these schooners were simply on their way up river to Dover, where businessmen are wide awake.”

$15,000 more was granted in 1894. This brought Dover’s total dredging appropriation to $164,000 over the course of sixty years. The river was straightened and deepened in many critical spots to a depth of five feet at low tide, a great improvement for the heavily loaded schooners. The three-masted J. Frank Seavey, 144 feet long, 34 feet wide, and over ten feet in depth, was able to offload 600 tons of coal to sheds directly on The Landing.

DOVER’S BLACK DAY

A late winter ice storm on March 1, 1896 ravaged the area. Rivers rose six to ten feet and huge ice flow crashed into bridge pilings. In Dover, three bridges were lost and dozens of businesses were destroyed or heavily damaged. All the sand, silt and debris which had been dredged out of the Cochecho River over the past sixty years were re-deposited on the riverbed once more. Six decades of improvements were undone and The Landing never recovered.

The Bracewell Building on Central Avenue sat on piers extended into the river and one-third of it collapsed. Casks of limestone stored on the docks ignited. The mills were closed down for three days and damages were estimated at over $300,000.

For a full description of Dover’s Black Day, please refer to the 1996 Dover Heritage Walk brochure or check the “Dover History Online” section of the Dover Public Library’s website, www.library.dover.nh.gov, for the “Calamity on the Cochecho” account.

THE DOVER NAVIGATION COMPANY 1877-1914

The DNC was organized in 1877 by a group of ambitious men looking for a profitable investment. Thomas B. Garland, clerk of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company, was elected president and B. Frank Nealley, owner of Dover’s largest dry goods store, became secretary-treasurer. Their first schooner, the John Bracewell, was built in Bath, Maine at a cost of $13,122. It was nearly 114 feet long and carried 350 tons of cargo. It did a brisk business in Dover, delivering coal straight to Dover wharves with maximum efficiency and minimum cost through the newly dredged river channel.

The Company easily recruited more investors through the sale of stock and were able to build new schooners in each of the following four years, each ship bigger than the last. Other DNC-commissioned vessels, built in subsequent years, had more difficulty negotiating the narrow channels and shallow depths of the Cochecho River. Two of the Company’s ships could not come to Dover at all.

The business continued profitable and netted 10% annual dividends for its stockholders. Grander schooners were added to the fleet until the Dover Navigation Company owned ten vessels:

Length Breadth Depth Cargo(tons) Cost

**Sch. John Bracewell (1878-1911) 113.6 29.2 9.1 350 $13,122

“handsomest and best built vessel that has come to Dover”: many trips to Baltimore

**Sch. Charles H Trickey (1879-1888) 120.1 32.2 8.1 350 $14,372

“splendid vessel built of the best material”: hauled coal for the mills

*Sch. B. Frank Nealley (1880-1889) 123.6 30.2 8.8 375 $16,480

“a noble vessel, one of fastest sailers”: paid her owners 113% profit

*Sch. Thomas B Garland (1881-1911) 126 32 11 500 $18,516

“highly please with the appearance of the craft”: docked primarily in Saco, Maine

*Sch. Zimri S. Wallingford (1882-1895) 127.7 30.3 9.1 450 $19,012

“Combines large capacity and light draft of water”: destroyed by fire in Virginia

**Sch. J. Chester Wood (1883-1892) 68.6 23 5.5 55

“Will load with 60,000 bricks for Boston”: the Company’s only brick schooner

Sch. John J. Hanson (1884-1914) 150.4 34.8 18.7 1000 $29,400

“cargo would fill 30 train cars”: never got closer than Portsmouth

*Sch. Jonathan Sawyer (1886-1907) 140 33.3 10.3 600 $19,404

“into the water like a thing of life”: 1,000 visitors on her first stop in Dover

**Sch. J. Frank Seavey (1888-1912) 144 33.9 10.2 600 $24,041

“a beauty T…and works like a charm”: brought largest cargo ever to Dover Landing

Sch. John Holland (1890-1893) 195.2 40.3 17.8 1800 $54,400

“a model of elegance from stem to stern”: too large to navigate the Cochecho River

* navigated to Landing wharves only after “lightering” further out

** navigated to Landing wharves with full cargo

The last ship, the John Holland, was hugely profitable at East Coast deepwater seaports. Unfortunately, it was involved in a collision with an English steamer off the coast of Virginia in 1893 and sank in just 25 minutes.

In 1894, Treasurer Nealley warned: “Rates of freight have ruled very low…and expense on vessels for repairs have been exceptionally large…” By 1898, profits exceeded losses by only $8,821. The boom in commercial shipping was slowing. The trend toward motorized and steam-run ships was growing as was railroad transport. The Company chose to “wind up” business in 1914 and sold off their remaining fleet.

RIVERFRONT BUSINESS

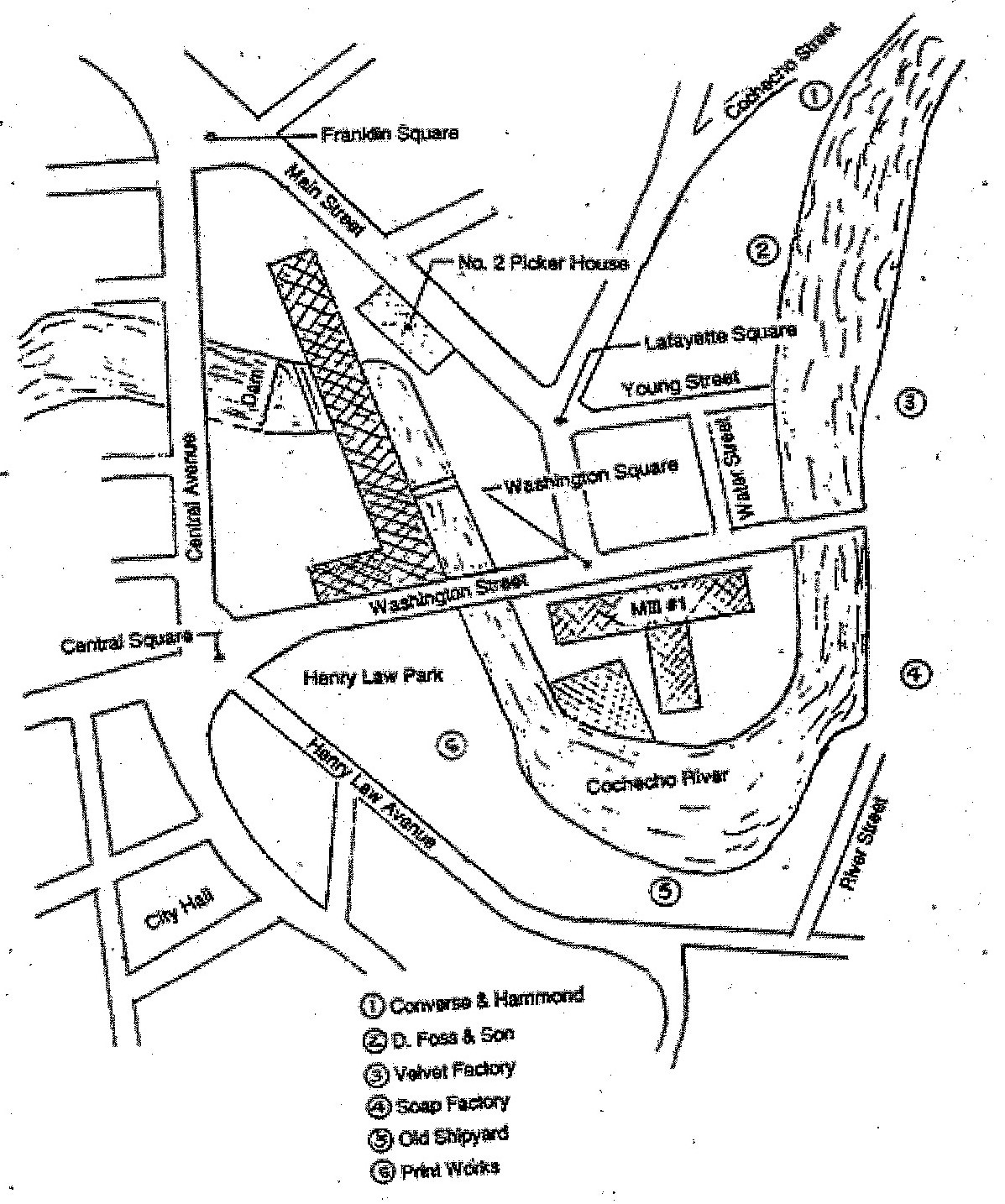

Although there were dozens of enterprises at the waterfront, seven large businesses dominated the area around Cochecho Street:

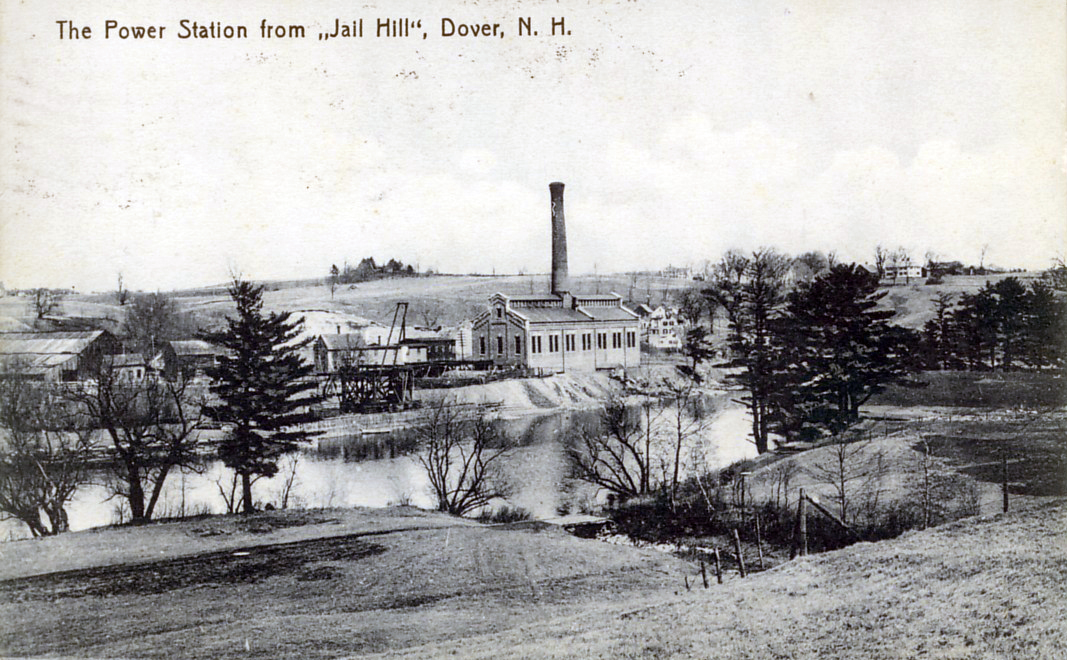

The Dover Gas Light Company was organized in 1850 and located its gasworks at the Landing. In 1891 the company was leased for twenty years to the United Gas & Electric Company. In 1905 they became known as the Interstate Gas & Electric Company and merged in 1909 with Twin State Gas & Electric. In 1914 Twin state advertised that “having absorbed all previous light and power interests in the City” that they were the monopoly in town. The foundation of the gas works can still be seen on Cochecho Street and Public Service Company of New Hampshire still owns the old power plant on the water, now occupied by the Dover Horse Patrol.

Russell B. Wiggin and William S. Stevens established a sandpaper and glue-making factory at 89 Cochecho Street in 1858. Wiggin & Stevens imported large quantities of sand, flint and quartz during the company’s early years, and most of these raw materials came by schooner to the wharves near The Gulf. By 1890, only glue (some 60 tons per year), was manufactured in Dover then shipped to a Malden, Massachusetts sister factory for use in making emery, sand and match papers. Eight people worked at the Dover branch of Wiggin & Stevens.

The Charles H. Trickey Coal Company kept dozens of schooners sailing up the Cochecho for thirty years. Their coal sheds could house 4000 tons of coal and the firm sold about 10,000 tons annually, imported to Dover from New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Charles Trickey originally bought the business in 1872 from Moses D. Page, and by 1876 had enlarged all its sheds and expanded to six pockets on the riverfront. Trickey’s did all the hauling for the Cocheco Manufacturing Company and employed 20 men and 16 horses.

A lumber yard at The Landing was started in 1874 by Joshua Converse and Edward Blaisdell. Located opposite the gas works at 17 Cochecho Street, they also carried lime, cement, plastering hair and pipe. In 1878 they became Converse & Hobbs, in 1883 Converse & Wood, and 1884 Converse & Hammond. In 1889, A.C. Place became Moses Hammond’s new partner when Joshua Converse retired. By 1891, Place was the sole owner and by 1898 it was known as the A. Converse Place Lumber Company. The business was immense, with an annual output of four to five million feet of lumber, 50 employees, and wharfage covering six acres. A. Converse Place additionally sold stone, slate, fire brick, interior mantels, guano, dried bone and other fertilizers.

D Foss and Son’s factory began on Portland Street in 1874 at the site of an old flax mill. Dennis Foss and his son, A. Melvin, manufactured wooded boxes and sold grain. Over time, they began to make doors, sashes, blinds, stair posts, rails, bobbins and spools. By 1900, 75 people were employed in their three story mill at The Landing.

Valentine Mathes was a retailer of gain, flour, groceries, coal, wood, shingles, clapboards, hay and straw from his store on Folsom Street, begun in 1879. In 1881, Mathes bought land and wharfage on the river and built a 50-foot coal pocket on Cochecho Street. He employed 15 people there until his retirement at the turn of the century.

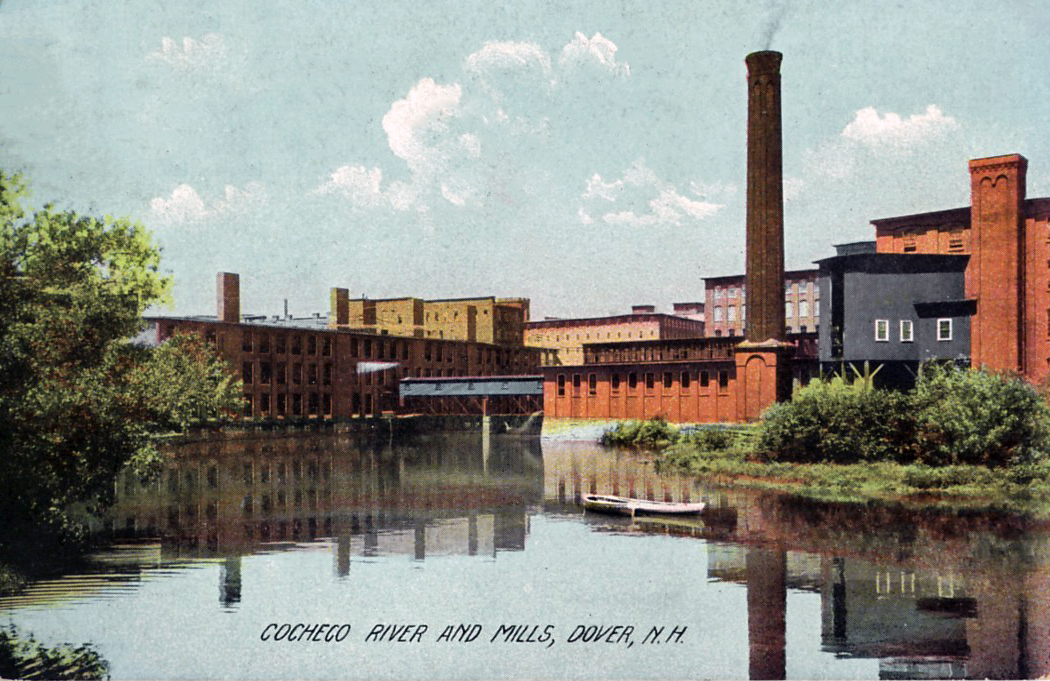

The most important business, however, was the Cocheco Manufacturing Company. The schooners imported the mills’ raw materials and exported their finished goods, but all these other Landing businesses were thriving at the port because of the mills’ needs.

D. Foss made their packing crates, Mathes could deliver their employees’ groceries, the gas and electric companies supplied their power, Converse Place their lumber and mortar, and Trickey fed their boilers. Without the gargantuan demands of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company, there would have been no need for these suppliers’ large inventories or services. Each business, although profitable on its own, was inherently dependent on the other for mutual survival. The old adage that “a rising tide lifts all boats” was especially true on Dover’s waterfront, both literally and figuratively!

BRICKYARDS

Dozens of local brickyards lined the clay-filled riverbeds along the Cochecho River. Even today, remnants and shards of red bricks can be seen barely buried along the banks at low tide. The earliest brickyard is said to have been Thomas Henderson’s at Dover Point. He sold it to Thomas Card in 1812. The names of the families involved in the industry include many old Dover names of long standing: Seavey, Loughlin, Pinkham, Ford, Coleman, Courser, Horne, Parle, Morang, Gage, Hanson, Lucas, Clements, and Roberts are just a few.

During the first quarter of the 19th century, Hanson Roberts provided one and a half million bricks “of the hardest variety” for the brick blocks nearest the water. In general, there were usually between 12-14 brick schooners operating successfully in Dover at any one time in the 1880s: Hattie Lewis, Triton, George W. Raitt, Chilion, Satellite, H. Prescott, Lillie, Emily A. Staples, Wilson and Willard, Addie, Delia, Estella, J. Chester Wood, Clara B. Kennard and Sadie A. Kimball were some of these vessels. Each could carry a cargo of approximately 60,000 bricks (value $150) and most were shipped to Boston. It is said that most of the 19th century buildings in the Copley Square area were constructed of Dover brick.

In 1889, Horne’s Yard had stored 500,000 bricks at their facility on Cochecho Street. In 1892, Capt. O.A. Clark made 33 trips to Boston with full loads of bricks. In 1893, J. Wesley Clements claimed he’d sold seven million bricks to Boston developers. Aaron Pinkham had 16 arches in his kilns and boasted that he’d produced 300,000 in just one week! Isaac Lucas, one of the last brickyard owners in Dover, said in 1923 that he’d estimate that over 40 million bricks had been made in Dover and that there was still enough clay in the riverbeds to “last 100 years or more.”

In the early 20th century, yard owners adopted the Fiske Brick Making System, an automated process. An operator and one helper could handle the same amount of work as 15 or 20 men with wheelbarrows. (Both the Dover Public Library and the (old) Dover High School on Locust Street were constructed with Fiske-process bricks in 1904-05.) This brickyard burned down on December 28, 1906. Many brickyards closed after this, but a few lasted through the 1920s.

PAYNE STREET AND MR. HENRY LAW

In 1825, the Dover Manufacturing Company (as it was known at that time), made two new streets in downtown Dover and built housing for their workers. Some were boarding houses, others duplexes, and still others single family homes. A family could rent a house for $75 a year, or $90 if they wanted a basement too. The two streets were named Williams and Payne: the first for mill agent John Williams, the second for Boston financier and Company President William Payne. Payne Street extended as far as George Street at this time.

In 1929, Henry Law donated to the city the land for Henry Law Park. Payne Street was renamed Henry Law Avenue in 1933 in honor of this munificent benefactor to the City of Dover. Mr. Henry Law was born in England in 1842, emigrated to Dover at age 21 and owned a harness shop. He began to invest heavily in real estate in Dover and became one the city’s wealthiest landowners. He was an active member of the Dover Park Department and his donations to the city built the swimming hole at Bellamy Park and the wading pool at Henry Law Park. He also gave the land for the armory (now the Dover Recreation Center) which was built in 1931. Henry Law died in 1938 at age 96.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.