Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

2005 Heritage Walking Tour

Dover Historical Society Heritage Tour Booklet

Garrison Hill: the Panorama Revealed, September 24, 2005 by the Dover Historical Society, Dover, NH, c. 2005.

In 1978, a group called Dover Tomorrow formed to promote the growth and prosperity of Dover. A subcommittee was tasked with promoting “appreciation of Dover’s heritage”. The Lively City Committee created the first Heritage Walk the next year. It was so popular that new tours were created every year, and held through 2007. By 1982, Dover’s historical society, the Northam Colonists, had taken over the research and creation of the Heritage Walking Tour Booklets. The information on the page below is a transcription of the original Heritage Walking Tour Booklet. The Library has a complete set of the Heritage Walking Tours if you would like to see the original booklets.

"GARRISON HILL: THE PANORAMA REVEALED"

Dover, New Hampshire

September 24, 2005

GARRISON HILL: THE PANORAMA REVEALED

Garrison Hill was formed during the Ice Ages into a geological formation known as a drumlin. IT was first mentioned as “Great Hill of Cochecho” in land grants during the 1650’s to several early citizens of Dover, including William Wentworth. What is now called Central Avenue was then called the “Cart way.” “Garrison Hill” referred only to the rise over which the Cart way passed, and was named for the Heard garrison, located near the top of the rise. In the late 1690’s, when Ebenezer Varney married a granddaughter of Richard Otis and came into control of much of the land in this area, the name “Varney’s Hill” took hold, and was used until John Ham bought the land from the Varney family in 1829. From that time on, the term “Garrison Hill” was used for the entire “Great Hill” area.

The Wentworth, Otis, Varney, Sawyer, and Ham families owned much of the land here originally and farmed the still-unforested crest of the hill. In 1696, Ebenezer Varney, a blacksmith and devout Quaker, built his home at the foot of the west side of Great Hill. Varney was a great friend and benefactor of the local Indians, and his home and his family were never in any danger during the Indian turmoils that plagued Dover in the 1700’s. The hill eventually became known as Varney’s Hill during the eighteenth century. In 1829, John Ham purchased Varney’s property and, by 1834, the name changed to Garrison. The Varney-Ham house remained in the Ham family until about 1920 when it was sold to Phillip Daum. The house was taken down around 1970, when the large apartment complexes in that area were constructed.

In the 1790’s, Captain Richard Tripe operated a boatbuilding enterprise on the side of “Varney’s Hill”. His house still stands today, set back on the right side of Old Rollinsford Road, just off Central Avenue. While the Hill might seem an odd place to build ships, it was not difficult to move them in snow during the winter. During the winter of 1795, Tripe hauled a fifty-ton schooner down the hill through three feet of snow to the Landing at the Cochecho River, three miles away.

By the 1850’s, Garrison Hill was well-known as a recreational site. When local Democrats wanted to celebrate the election of James Buchanan to the Presidency, they purchased a cannon which had been captured from the British in the War of 1812 and stored at the Portsmouth shipyard. After hauling it upriver on a gundalow, they had a team of oxen move the cannon to the top of Garrison Hill. Speeches, fireworks, and a bonfire were planned, but unfortunately the cannon, nicknamed “The Constitution”, misfired, killing the two young men who were loading it. It was not used again until 1875, when, in honor of the Battle of Bunker Hill, it was fired for the July 4th Centennial Celebration atop the hill. Repeatedly vandalized in the 1960’s, the cannon was eventually moved to the Woodman Institute, where it rests today in front of the Damm Garrison House.

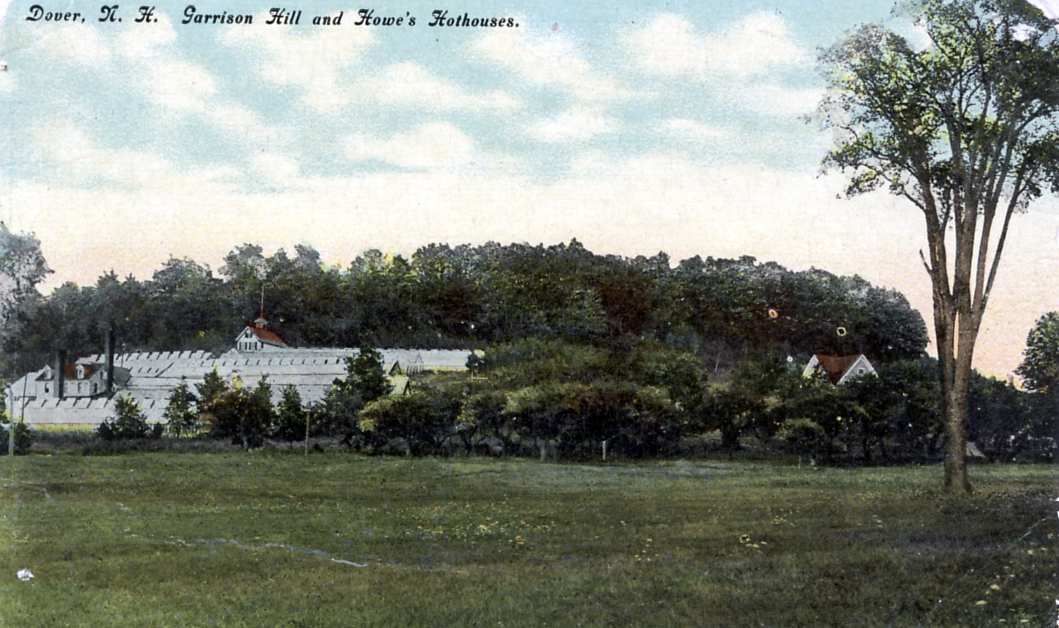

By the mid-19th century, a small village called Mechanicsville had developed around the base of Garrison Hill, serving as a stopping place for teams of horses and oxen that were traveling from the mountains to the shipping docks at Dover Landing. Among the tradesmen there were a blacksmith, a butcher, a saddler, a tin store owner, a tanner, and a wheelwright. Mechanicsville

residents also included several farmers, a nurse, a dressmaker, a barber, a baker, a hatmaker, a vinegar dealer, and Wiggin’s hotel and tavern. The Garrison Hill district school had 84 pupils. A later enterprise that developed here were greenhouses which were built in 1885 by Henry Johnson. There were destroyed by fire, but rebuilt in 1893 by new owner Charles Howe. Howe expanded the business, increasing the number of greenhouses to fourteen by 1901, “the busiest and largest conservatory in the state.” Howe sold to E.S. Shortridge in 1921. Now known as Garrison Hill Florists, these greenhouses were among the largest in New England. This business moved further up Central Avenue to Page’s Corner after a near-hurricane caused $50,000 damage to the greenhouses on the Hill on November 26, 1950.

HARRISON HALEY

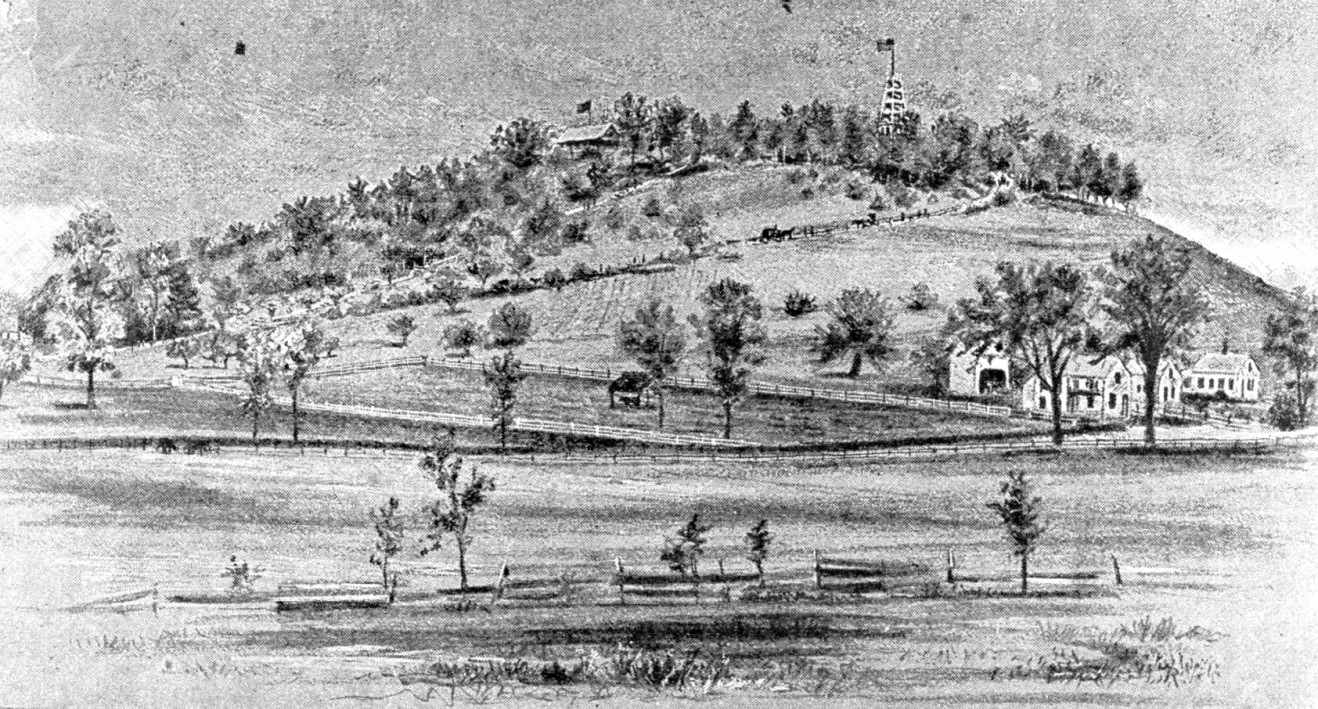

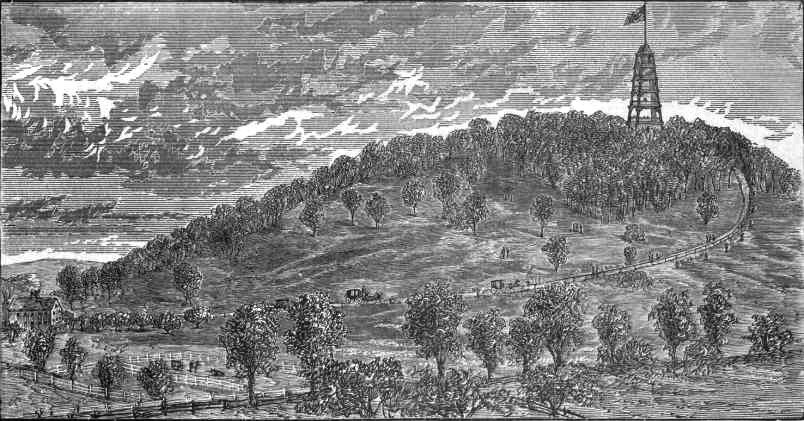

By 1880, the top of the Garrison Hill was jointly owned by Joseph Ham and a young entrepreneur who was cashier at the Cocheco National Bank, Harrison Haley. Haley built, for $1000, a wooden observatory sixty-five feet high, designed by architect B.D. Stewart and modeled on a similar structure at Coney Island. Known as “Haley’s and Ham’s Outlook,” the tower was five stories high with a mansard roof and open balconies on every floor.

A ten-cent admission was charged to climb to the top where Haley had installed a telescope through which the public could see Mount Washington, ninety miles away. Over 6,000 tickets were sold the first year. The observatory also had a small twenty-five-square-foot restaurant in its base where light lunches and cold drinks cold be purchased. The top of the hill was landscaped with hiking trails, a six-acre picnic grove, and a roller skating rink with removable sides. Young Dover men came in droves to play in the roller-hockey league games at the rink. Haley also had plans to install a 102-foot high toboggan run that would extend 2,000 to 3,000 feet down the hill, but this project never materialized in his lifetime.

In 1885, Dartmouth College professor E.F. Quimby completed a topographical survey of the views from the top of Garrison Hill and computed the distances to various landmarks in each direction. Quimby determined that forty-one cities and towns in Maine and New Hampshire could be sighted from the observatory.

In 1888, the City of Dover purchased eight acres of land at the summit of Garrison Hill from Harrison Haley. A two million gallon reservoir for city water was constructed there the next year, and thus ended much of the recreation activity at the hill. The roller skating rink was removed to Burgett (Central) Park and the crowds began going to Willand Pond for amusement and entertainment. The observatory remained until June 27, 1897 when it was destroyed by a fire caused by a careless smoker. There were some pleas for rebuilding the tower, but the City Council did not have sufficient funds for its reconstruction.

JOSEPH SAWYER

Joseph Bowne Sawyer was born on November 20, 1832, in the home built by his blacksmith father on Garrison Hill, at what is now 756 Central Avenue. Joseph grew up in a neighborhood that was steeped in Sawyer family history as well as the earliest history of Dover.

The son of Levi and Hannah (Pinkham) Sawyer, he came from a strong Quaker family. Levi Sawyer was the son of Stephen and Mary (Varney) Sawyer, and he too was born in a home built by his father across the street, at what is now 757 Central Avenue. Stephen was the son of Jacob and Susanna (Estes) Sawyer, who lived at what is now 751 Central Avenue. Joseph’s mother, Hannah Pinkham, was a direct descendent of both Richard Pinkham, one of the original settlers of Dover, and Richard Otis, who was killed by Indians in the 1690’s. (His grandmother, Mary Varney, was also a direct descendent of Richard Otis.)

Joseph was educated in the Dover public schools and the Franklin Academy. He went west about 1853, and was employed first in Dubuque, Iowa, and later in the management of steamboats on the Mississippi River. After the Civil War, he moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he was involved in the oil business, being a charter member of the Oil Exchange there. When his health began to fail, he retired and began spending his summers at Poland Spring, Maine, where he met Abbie Marticia Sturtevant. Abbie, the only daughter of Warren and Nancy Sturtevant, was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on October 6, 1853. Joseph and Abbie were married in 1894, and often visited Joseph’s sister, Elizabeth, at the family home in Dover. Upon her death in 1896, the home was left to Joseph and the couple moved back to Dover to live there.

During their summers at Poland Spring, Joseph became friends with a retired businessman of Boston and native of Dover, Arioch Wentworth. Joseph persuaded Arioch, whose family roots also ran deep in Dover history, to donate to the building of the city’s first old age home, and, through his efforts, $100,000 was given toward that goal. Built in 1898, the Wentworth Home for the Aged still bears the granite plaque donated by Joseph. He was elected President of the Board of Trustees of the Home, and served in that capacity until his death on July 5, 1905. Abbie was also active in the affairs of the Wentworth Home, as Trustee and Manager, until her own death on April 16, 1911.

Abbie bequeathed $3,000 to the City of Dover for the construction of a new Observatory atop Garrison Hill, to be made out of iron so that it would not burn, and requested that it be named after her late husband, Joseph. She also provided $4,000 for its maintenance and $500 for the construction of a new road to the top of the hill from Central Avenue. Dedicated on August 2, 1913, the new iron observatory was an instant attraction, and remained popular and frequented by people in all weather and all seasons for many decades.

While Haley had failed to capitalize on the Hill in winter with a toboggan run, a toboggan slide on the northerly slope of the Hill was opened by the city in February 1924. The Dover Tribune reported on February 7 that several thousand people from Dover and nearby towns turned out to attend the opening evening of the slide, with the first ceremonial run at 8 p.m. So many people came with their toboggans, in fact, that there was too much congestion at the top of the hill, and after an hour’s coasting, the Park Commission decided to close for the evening, in order to erect a sliding table from which the toboggans could be dispatched more promptly by the attendant, in order to ease the congestion.

By the 1950’s the toboggan run had been replaced by a municipal ski area, with two ski slopes, a rope ski tow, and a warming hut at the base. The Parks Department offered ski classed in the winter, and the hill and park enjoyed year-round visitation by the public.

DECLINE AND REBIRTH

The ski slope was the first to succumb to rising costs and dwindling use at Garrison Hill in the 1960’s. Faced with fewer large snowfalls each year and lack of funds for snow-making equipment, the municipal ski slope was closed in the 1960’s. Its buildings fell into disuse and neglect and subsequent vandalism. The City stopped maintaining the tower during the same time period, with the last painting of the structure done in the 1950’s. Fittingly, this was done by the company of a descendent of Arioch Wentworth and lifelong resident of the Garrison Hill area, James Wentworth. The tower quickly fell into disrepair, with wooden decks rotting out and the unprotected iron girders wasting away from acid rain and the elements. The legs became bowed from the effects of rust. Faced with increased vandalism, the City finally removed the bottom sets of cast iron stairs and fenced off the tower in the 1970’s.

The City constructed a new enclosed water reservoir on Garrison Hill in the early 1970’s. The open, granite-lined reservoir that had served the city since 1888 was filled with demolition debris from several houses in the Waldron Court Urban Renewal area and grassed over. In 1973, the City of Dover petitioned the Strafford County Superior Court to change the terms of Abbie Sawyer’s will to allow the City to tear down the tower and replace it with a granite marker, using the maintenance trust funds to do so. At this point, a group of local citizens, the Garrison Hill Park & Tower Committee, organized and began investigating, instead, a renewal of the tower. After several court decisions, twenty years of fundraising, thousands of donated volunteer hours and dollars of donated materials, a new steel tower was built in 1993, using copies of the original 1912 plans found in City vaults and at the Woodman Institute. The tower dedication ceremony was held August 6, 1994. A public park was created around the base of the tower. Garrison Hill is once again an active part of the recreational life of the City of Dover.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.