Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

2006 Heritage Walking Tour

Dover Historical Society Heritage Tour Booklet

Factory on Fire! by the Dover Historical Society, Dover, NH, c. 2006.

The Cocheco Mill Blaze of 1907 Revealed

Dover, New Hampshire

May 19-21 and May 26-28, 2006

When Charles H. Fish, Agent of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company, left his home on Locust Street for his brief walk to work early on the morning of January 26, 1907, he may already have sensed that something was terribly wrong.

As he approached Dover’s City Hall, he began to smell smoke, and people were asking what was happening at the mill. Confused, and unsure how to answer the questions, Fish quickened his pace and ran towards Central Avenue. In the existing low light of the approaching dawn, he looked beyond the Print Works towards Mill No. 1. One of his worst fears was realized: the factory was on fire!

IN THE BEGINNING

In September 1895, Charles H. Fish moved to Dover to serve as agent for Dover’s largest employer – the Cocheco Manufacturing Company.

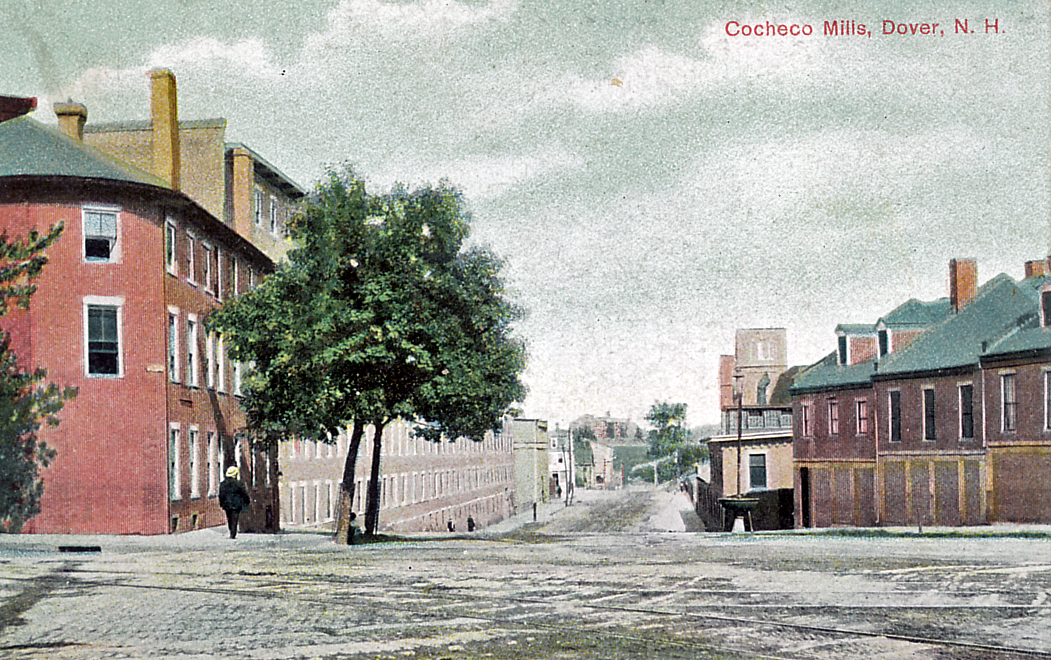

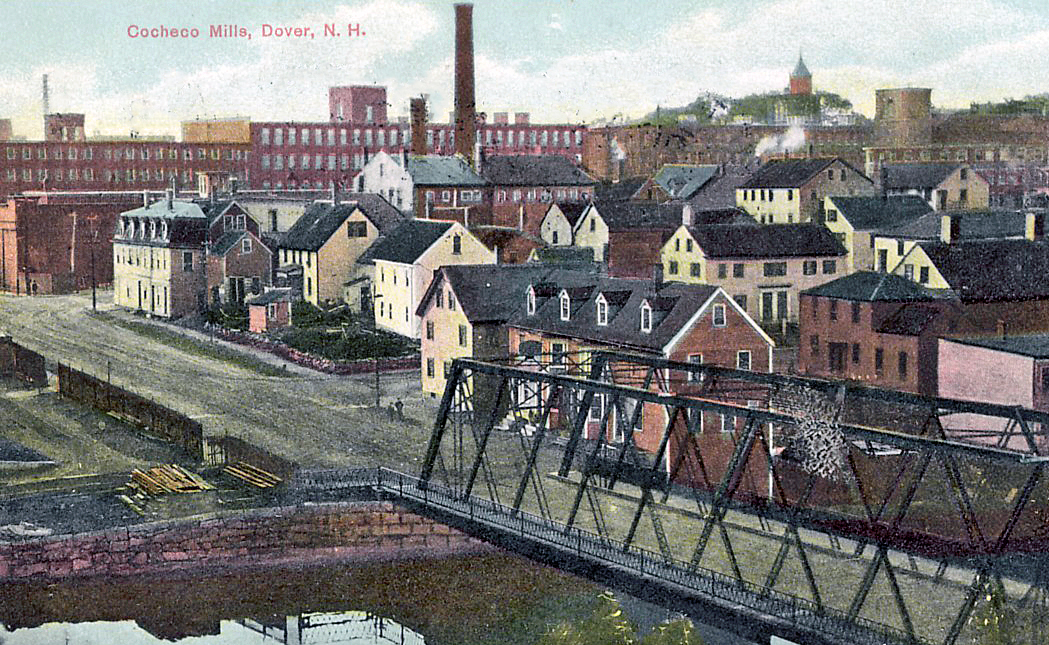

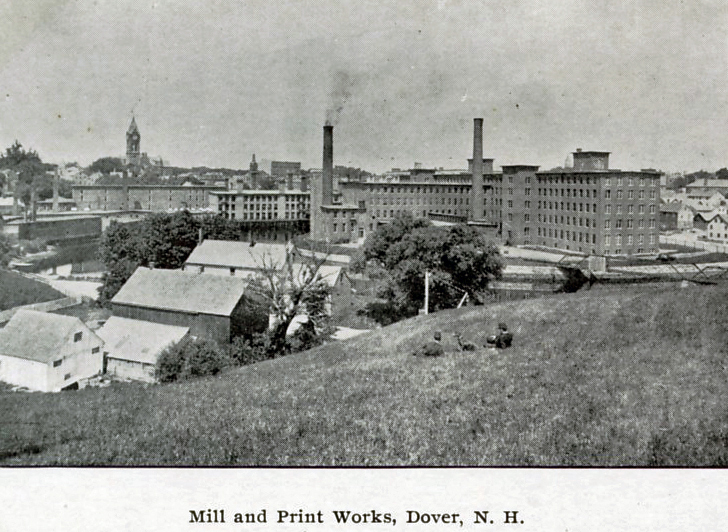

At the time of Agent Fish’s arrival, the Cocheco Mill Works employed over 1600 people; its five mills and print works housed 128,000 spindles, 3000 looms, and manufactured millions of yards of cotton cloth a year. The fifteen buildings of the Print Works produced over 65 million yards of finished fabrics that were renowned world-wide for their quality.

The Cochecho Manufacturing Company began as the Dover Cotton Company in 1812, when mill founders John Williams and Isaac Wendell began producing cotton cloth at the “Upper Factory Falls” (near present-day Liberty Mutual). By 1822, the Dover Cotton Factory was moved closer to town and construction began on several large brick mills, many of which still remain downtown today. But with the growth came the need for additional capital. Investors from Boston were solicited and local control was eventually lost.

By 1844, the Cocheco Manufacturing Company (CMC) owned five mills on both sides of the Cocheco Falls and the large print works had just been built on Payne Street (now Henry Law Avenue) to imprint the cloth with colorful designs.

By the turn of the 20th century, the CMC was the heart of the Garrison City and its mills provided thousands of jobs for men, women, and even children.

A large component of the original workforce were local farm girls, lured to the big city because of the jobs paid well and provided stable opportunities to live on their own for the first time. As a further incentive to work in the mills, housing was provided in boarding establishments (at a cost of course) and strict rules kept the girls on the straight and narrow.

As the eligible workforce in the area grew scarcer, mill owners found another supply of workers in Dover’s new immigrants. First were the Irish in the mid-1800s, followed by the French Canadians in the 1870s through 1890s, and finally the Greeks after the turn of the century. Each nationality established their own neighborhoods. The Irish settled along Payne Street and around St. Mary’s Church (Dover’s first Catholic parish) between First and Fifth Streets. The French generally lived near Broadway, Ham and New York Streets and the Greeks settled around School, Portland and Main Streets. Many worked in the mills.

WORKING CONDITIONS

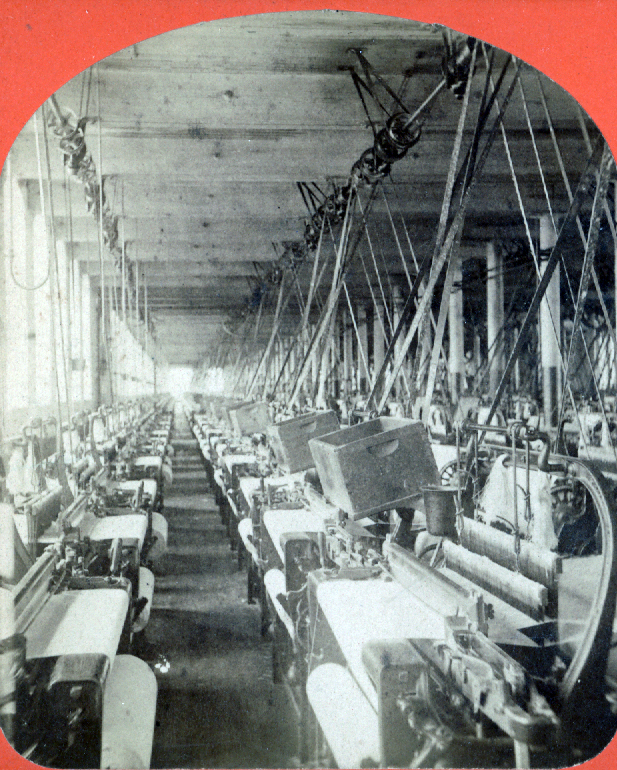

Work in the mills was dirty, noisy, monotonous, and continued six days a week: Monday through Friday 6 am to 6 pm, and Saturday 6 am to Noon. Sundays were the only days off.

The temperature in the mills was never dropped lower than 70-75 degrees all year long and often exceeded normal comfort levels. The hot air was necessary to provide the humidity needed to work with the cotton thread. Some parts of the mill were even warmer: the slashing rooms were the hottest as it was here that the thread was starched in huge baths to strengthen it.

It was always loud in the mill. The thousands of machines that transformed the raw cotton into the finished cloth were large and extremely noisy. The machinery was driven by leather belts, some 30 inches wide, and powered by steam.

Cotton dust flew everywhere there was raw cotton or weaving. Small lint fibers were in the air, around the belts, in the machines, on the floor, in the hair and eyebrows of the “operatives” (as the workers were called) and in the lungs of those who breathed in and out all day in this shuttered environment. All windows had to stay closed to prevent air currents or drafts from blowing or disturbing the thread.

There were also cockroaches and rats. Living amidst the hot steam pipes, the roaches would often nest in the workers’ personal clothing which was hung up during the day. It was common practice to shake out your clothes prior to changing, either before or after work, to scatter the roaches.

There were several types of workers in the cotton mill. At the top was the Agent, the CEO in charge of the mill’s entire management. Below the Agent, other bosses – always men – included the Superintendents, who were in charge of an overall division in the mill such as the Weaving Room or Spinning Room. They reported directly to the Agent. Next were the Overseers and Second Hands who supervised a floor or an operation. There were the shift foremen.

Beneath the bosses were several classes of specialized workers who were paid more because of their valuable skills. These were the loom fixers, mule spinners, and slashers. The loom fixers repaired malfunctioning looms and thesre men were actually unionized. The mule spinners operated large spinning machines that rolled back and forth to strengthen the cotton thread, while the slashers starched the thread to strengthen if for weaving.

Printery workers also had special skills necessary to operate the massive and bulky presses that added color and designs to the finished cotton material.

At the heart of the mill were the lowly operatives – the weavers who ran the looms that took the cotton thread and wove it into cloth. It was here that CMC first began to make money and was here that thousands of women worked in the looms that were so noisy that one had to scream into the ear of a co-worker in order to be heard.

MILL NO. 1

Mill No. 1 was constructed between 1876-1878 and was less than 20 years old when Agent Fish joined the Corporation. It had five floors and an ell of four stories. Light duck and napping fabrics were produced here by 600 workers using 50,000 spindles and 1400 looms.

The first two floors contained the weaving rooms; the carding room was on the third floor, and the spinning rooms were on the fourth and fifth floors.

A large 20-foot high, 65-ton iron wheel, powered by an adjacent steam plant, ran three large (one 30”and two 25” wide) leather belts that ran throughout the mill shafts that fed other smaller machine belts which ran the individual machines.

As in all the CMC mills, cotton cloth produced in Mill No. 1 started out as bales of raw cotton shipped to Dover by rail. From their large warehouse on Chestnut Street, the 500-poung bales were delivered to the mill by teams of horses and carts. The cotton bales were then broken open in the picking room and lifted to the third floor car room by a freight elevator. There, the raw cotton was fed into carding machines to clean and straighten the cotton fibers which eventually would be turned into thread.

Once made, the thread was wound on wooden bobbins and sent back down the elevator to the lower two floors where the bobbins would be placed on the looms. Doffer boys and girls, some younger than twelve (state law, rarely enforced, said a child had to be fourteen to work), were charged with removing empty bobbins and replacing them with filled ones while the weavers kept the machines going. The woven cloth would then be removed, checked for quality, and forwarded to the print works or the folding rooms.

FIRE SAFETY

Fires in the cotton mills were relatively common at the turn of the 20th century. With their oil-soaked floors, bins of raw cotton, and lots of heat-producing machinery, the mills were prone to fire. It was an expectation of the job that workers would immediately used whatever means necessary to snuff out a blaze. In most cases, a pail or two of water would suffice to put out a small machine fire.

The Dover mills were built with fire prevention in mind and their insurance agent, the Boston Manufacturers Mutual Fire Insurance Company, had rated CMC “excellent” prior to the fire. Mill No. 1 had 800 water pails along its interior walls, water stand pipes, and hose lines on each floor in its towers, hose lines in the center of the mill, tinned fire doors leading from the tower stairs, and a sprinkler system. In addition there was the 55-man paid CMC Fire Department.

Mill No.1’s lone fire escape was a metal ladder located at the backside of the ell near the river. Attached to the building, the ladder ran from the roof to the ground. It was expected that the employees could use the stairways in three of the towers or the stairs at the end of the ell to escape any serious fire. It was also assumed that workers on the top (fifth) floor could escape via the eight windows that were over the ell, then walk across that roof to the fire ladder.

Unlike today, the mill did not have fire exit signs nor did management practice any fire drills. It was simply expected that the employees would know what to do and that no other training or information was needed to escape a fire.

SOMETHING’S GONE WRONG

Just before power was to be supplied to the machines on January 26, 1907, a sprinkler on the fourth floor went off for not apparent reason. (It was later determined that the sprinkle had been struck or that the solder around it had weakened.) As water flowed from the sprinkler, it began to soak the machinery and floor. Fearing that the water would seep down to the third floor, and thinking he cold repair the leak, the foreman on the fourth floor sent a worker to the first floor to turn off the water for the sprinkler system.

In following his boss’s instructions, the worker had effectively shut off 1/3 of the sprinklers in the mill. Unfortunately, no other floor was advised of this and no one else was aware the water had been turned off.

Within minutes of the sprinklers being turned off, Robert Monarch, third flood card room overseer, began to smell smoke. Looking around, he saw smoke and sparks coming out of a six foot high wooden belt box which covered the leather drive belt passing through his floor to the fourth floor above. The tall belt boxes prevented people from walking into the belts that ran throughout the mill. This particular box was located directly underneath the sprinkler that had burst on the fourth floor above. The water, it was determined later, had caused the leather belt to slide and rub against the wooden box, causing friction and sparks.

Unaware that the sprinklers had been turned off, Monarch and two others watched as sparks flew across the room and into dozens of open drawing cans on the floor which contained raw cotton. The contents immediately caught fire and flames spread throughout the floor.

Monarch and his men attempted to fight the fire with the hoses in the towers and with their fire pails, but it was too little, too late. The fire quickly raged uncontrollably. One worker ran to the fourth floor and warned everyone to get out. More sparks were carried down on the still-running leather belts to the lower floors, and the vocal alarm spread to get out of the mill. But no one told the fifth floor employees who were still waiting for the day’s work to begin.

TRAPPED

A worker from the fourth floor ran down to the first floor to turn the water back on for the sprinklers. He was barely able to reach the water valve because the hall was blocked by escaping and panicked operatives. He forced his way through the crowd and turned the water back on. Yet, within a short time, the water pressure began to fall: the fire had melted off so many sprinkler heads that the amount of available water pressure had been reduced drastically. Ironically, in order to increase water pressure for the hoses, the sprinklers were again shut off.

After word of the fire spread downward through the mill, most workers on the lower floors were able to escape. But those on the upper two floors found themselves trapped by the smoke-filled stairways. Desperation drove the men and boys to the windows, but they were frozen shut due to the high temperatures inside the mill and the sub-zero temperatures outside. Unable to manually open the windows, tools and fists were used to break the glass and get some fresh air.

As blinding smoke continued to fill the stairways, the few lights in the building went out when the main steam engine caught fire and stopped. Sparks had carried on the belts all the way back to the engine room and set the protective wooden wall around the large iron wheel on fire.

With the sun still not up and thick smoke blocking what little light there was, darkness filled the upper floors of the mill. The screams of those trying to escape the fire combined with the sounds of breaking glass and the yells from the growing crowds outside the mill replaced the noises of once-running machine belts and spinning machines on the fifth floor.

EMERGENCY

Outside the mill, the alarm was sounded when CMC Engineer William Hanson, working on Mill Street, saw flames in Mill No. 1’s third floor windows. Hanson ran to Fire Box 9 at the corner of Main and Washington Streets and pulled it, signaling the Orchard Street and Broadway Fire Stations. The Orchard Street Station sent steamers Cocheco 2 and Fountain 3; the Broadway Station dispatched three hose companies and the Hook and Ladder.

When the fire department arrived, smoke was pouring out the mill and the operatives were running out of the building. Others were trying to get back in to gather clothing and pay envelopes they had left behind. Agent Fish arrived as the workers were exiting and he went up into the tower to the third floor to witness the fire. Guards were posted to prevent any more employees from reentering the mill.

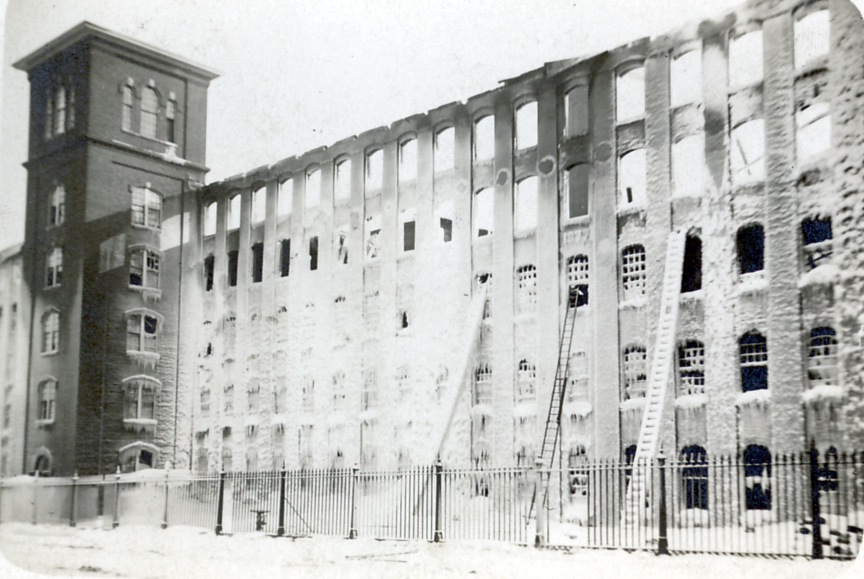

The frigid temperature, ranging to 25 below zero, initially prevented Dover’s firefighters from drawing water to fight the blaze as their steamers’ pipes froze. The steamers returned to their stations to thaw out. When hoses were used, water froze inside them and they burst. Rolled up fire hoses inside the mill, probably never used or tested, were useless as their rubber lining disintegrated and clogged the nozzles preventing any water from flowing. And when the water was turned off the clean out the nozzles, the hoses froze.

As word spread about the fire, many townsfolk came to witness it or to look for missing family members. Many came either on horseback or in horse-pulled wagons and sleighs and, in the process of getting close to the fire, valuable fire hose was cut by the horses’ hooves as they rode over it. This further delayed all fire fighting efforts.

FIRE FIGHTER CAVALRY

A call for help was sent to Portsmouth Fire Department. Boarding a special train, the Portsmouth firefighters and their equipment were transported to Dover and sent directly to the fire. Within 55 minutes, Portsmouth FD’s steamer Sagamore 1 and a hose wagon were on the scene. Like the Dover steamers before them, the Portsmouth firefighters also had a frozen steamer and they, too, had to be sent to the Orchard Street Station to thaw it out prior to use.

Once the steamer was functioning, Sagamore 1 was sent to the lower Washington Street Bridge, adjacent to the mill, to draw water directly from the Cochecho River. But as they began to suction, their hoses also failed and steamer was moved to a Young Street hydrant where it remained throughout the day and night.

Two Dover steamers were used during the fire. Cocheco 2 was the oldest of the three Dover steamers (one steamer was out for repairs), having been purchased in 1865. It remained at its post on the Lower Washington Street Bridge, pumping water for 16 ½ hours straight.

A HEROIC RESCUE

During the fire, several of those trapped on the fifth floor managed to break a window on the backside of the mill facing the river. Taking ropes off machines on their floor, the men fashioned an escape rope and threw it out the fifth floor window. Six men attempted their escape down this rope, which began to ice up immediately after it was thrown out. Four of the men managed to descend the rope to safety but suffered severe rope burns on their hands. Two other men using the rope fell shortly after getting on it. One, James Ashburn, fell four stories and later died. Another, William Turner, slid down the rope to the fourth floor where he slammed his hip into the window sill. Turner lost his grip and fell four floors to the frozen ground.

Injured badly, Turner was taken to a tenement house across from the mill where he was briefly seen by a doctor and put on a sleigh to Wentworth Hospital. Seventeen weeks later, Turner was finally released from the hospital, sufficiently recovered from near-fatal head and leg injuries.

In October, 1908, William Turner filed suit against CMC for providing an unsafe work place.

While Turner and the others were escaping from the fifth floor on a rope, ex-Dover Alderman James Whalen saw four other people trapped on the fifth floor. Whalen recognized one of the men as James Connor, the overseer of the fifth floor. Connor was yelling out from the window for help. Whalen and others in the crowd attempted to tell Connor about the ropes on the back side of the mill, but he did not hear them.

The Dover FD brought a ladder to the back of the mill. It was too short, so another was brought, also too short. A large box was placed under the ladder in an attempt to get more height, but this nearly caused the ladder to fall and the idea was abandoned.

Finally, Dover Fire Lieutenant William Bradley came up with an idea to use a rope and pole to save the men. With Dover Fire Captain John McDonough holding steady to the bottom of the ladder, Bradley climbed to the top of the ladder, Bradley climbed to the top with the rope and pulled up the long pole. From his perch at the top of the ladder, Bradley hoisted the pole up to Connor and threw up one end of the rope. Connor lashed the pole to the window sill while Bradley tied his end to the ladder. Bradley then instructed the men to slide down the pole to him and he would assist them on to the ladder.

Each man did as he was told and, with Bradley standing at the top of the ladder, he assisted each one off the pole onto the ladder.

One of those rescued, identified in Fosters Daily Democrat only as “a Frenchman,” couldn’t wait his turn to get down the ladder. He immediately swung underneath to the backside of the ladder and descended hand over hand on the rungs (without his feet touching the rounds!) and bypassed those above him to reach the bottom.

58 HOURS LATER

A little over two days later, the fire was declared over. Though there were still smoldering ruins and the sounds of crashing machinery falling through the burnt floors for a few more days, the fire itself was out. The task of clearing the debris and accounting for all the workers began shortly after.

The fire had claimed the top two floors of the mill and a part of the third. The brick exterior walls remained solid and the towers were never touched by the fire. During the blaze, the towers had been used by firefighters as interior ladders. They remained there, spraying their fire hoses onto the burning floors and later into the debris that collapsed inside the brick outer walls and towers.

Family members, co-workers and Company representatives attempted to gather all the information about missing workers. Eventually everyone was accounted for and four bodies were removed from the ruins. Two were burnt beyond recognition and the public was asked to assist in identifying them.

Both bodies were placed at Glidden’s Funeral Parlor and “hundreds of people” stopped by for viewing. In the end, the bodies were identified.

Three of the four who had died were young boys who worked in the mill as doffer boys or fillings boys. Agent Fish said that three of those who had died had returned to the mill after leaving to retrieve clothing or pay. Mill No. 1 employee and fire survivor Anna Gingras, who was 13 at the time, remembered Alfred Barron, 18, going back into the mill to Annie Roundtree’s clothes. He never returned. Barron was later found dead in the rubble of the mill.

The five who died were identified as Constantine Eleopuplos, 16; John Necolopulos, 17; Alfred Barron, 18; John Cosgeren, 16; James Asburn. A sixth mill worker, Oliver J. Clark, 55, died two weeks after the fire.

LIKE THE PHOENIX

Just 32 weeks after the fire, Mill No. 1 was again in operation. Construction had begun immediately after the last embers were put out. Displaced mill workers were offered jobs in other mills and many were offered eight-hour shifts. Workers were even paid for the day of the fire.

In constructing the new Mill No. 1, Agent Fish added a fifth floor to the ell and removed the old power plant. Electricity would now come from multi-boiler CMC plant across the street which powered the other Corporation mills. Access to the sprinkler valves was also improved when all water valves were relocated above the hall floors. And many of the looms and machines were salvaged from the fire and reused in the new mill.

CMC GOES ON TRIAL

The reopening of the mill in October 1907 was not the end of the Mill No. 1 fire story. In October 1908, the trial of William Turner vs. Cocheco Manufacturing Company took place at the Strafford County Court House on Second Street.

Claiming CMC had provided an unsafe work place, injured mill worker William Turner sued his employer over the lack of fire escapes at the mill during the fire. During the weeklong trial, 24 witnesses were called and over 475 pages of testimony and evidence were taken.

In defending its claim that the mill was as safe as any other in the country, CMC Attorney Albert O. Brown of Manchester, said, in his opening statement:

…All the law requires of an employer…is to furnish a reasonably safe place for the employee to work in…Now it is our contention that was done….There is another matter of law…and that is the doctrine of assumed risk…An employee assumes the risk of the his occupation of the danger of the occupation…even if these are in addition to the risks that are obvious…

William Turner’s attorney, John H. Bartlett of Portsmouth (later NH Governor in 1919-1921), said that it was not his client’s responsibility but that of the CMC to provide a safer work place.

The Court will tell you that it is the duty of the master to exercise ordinary care to provide a reasonably safe place for his employees to work, and that the employee…has the right to rely…upon the fact that the master has done his work; and that is the common sense of it.

In this David vs. Goliath showdown, the Dover community (and those in the greater Seacoast) watched intently for five days as a former immigrant was pitted against Dover’s largest employer.

On October 17, 1908, after 9 ½ hours of deliberation, the jury found in William Turner’s favor and ordered the CMC to pay him the sum of $12,158 for providing an unsafe work place.

THE COCHECO MANUFACTURING COMPANY GOES SOUTH

Following the trial, Agent Charles Fish resigned in November 1908 and later worked for the Knight Cotton Mills in Rhode Island. A grand going-away party was given in Fish’s honor and the employees gave him a “massive loving cup beautifully engraved” in remembrance of his time in Dover.

In 1909 the Cochecho Manufacturing Company was sold to Pacific Mills of Lawrence, Massachusetts. By 1913 the Print Works had closed and its machinery moved to Lawrence. The Print Works buildings were torn down. In 1937 the Cocheco Division of the Pacific Mills permanently closed, as the cotton manufacturing industry had moved closer to the raw materials in the south.

Today, Mill No. 1 is known as One Washington Center. The diverse businesses occupying the mill still provide dozens of jobs to the Dover community and, though it no longer produces cotton cloth, it is still a vital economic cog in downtown.

A LESSON TO BE LEARNED

Perhaps Agent Fish best summarized the changes that were to come regarding accountability when he spoke, just months after the deadly fire, in October of 1907 at the 83rd meeting of the National Association of Cotton Manufactures in Washington, D.C. Charles H. Fish said:

“It is the old story of the barn door and the horse, but it is an ill wind that blows nobody good and I believe that the lessons of this fire will in time go a long way towards preventing its re-occurrence.”

Special thanks to Washington Street Mill, LLC, owners of One Washington Center, for allowing us to reveal so many areas of their mill and to Corey Stevens, building manager, for his help in staging this production.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.