Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

Flu Epidemic of 1918 Strikes Dover

Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 Strikes Dover

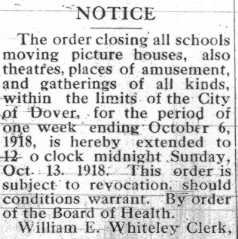

Spanish Influenza first appeared in Dover on September 17, 1918. Patients, mostly from the shipyards in Portsmouth and Newington, were under medical care in Dover. Clarence Post was the first to die of the flu, on September 20. He was only 27 years old. Five days after his death, the health board issued a general order closing schools, theatres, and any kind of public gatherings. They were too late in acting; the disease had already taken hold. His was the first of many deaths.

Citizens of Dover were given mixed messages at the start of the epidemic. The September 24th Foster’s Daily Democrat headline warned “Inluenza Epidemic Here”. Local physicians had reported a number of cases to Health Board officials in which "virtually all instances the symptoms are the same; that is, sudden onset with chills, severe headache, pains in the back and elsewhere, flushed face, some soreness of the throat, fever from 101 to 104 with a rather slow pulse". The Dover Health Officer William Whiteley described the symptoms of the flu “fever, general aching of joints and heads, catarrh of eyes, nose and bronchial tubes. It lasts about three days and is without serious results. Deaths when they occur are due to secondary infection such as pneumonia and nephritis.” He urged the public to remain calm and not to mistake the usual colds or “grippe” for the Spanish Flu. Officer Whiteley did not wish to institute a quarantine as that would be a hardship on everybody. Instead, he suggested refraining from coughing or sneezing, or attending public meetings.

Two days later the Dover Tribune said “If one were to believe all the street rumors prevalent the past few days, half the people of Dover are afflicted with the Spanish Influenza, but to the contrary, Health Officer Whiteley who ought to be some authority stated to a Tribune reporter Wednesday noon that not a single case of the epidemic with the symptoms of the disease … had been reported to his office.” The Tribune goes on to comment that while there is indeed a great deal of sickness in town and the Wentworth Hospital is filled to capacity, it is “nothing more than what ordinarily happens following a periodical quiet spell among the doctors and undertakers.”

By September 27 it was not possible to deny the existence of the flu in Dover. It was estimated that 800 - 1000 people in Dover were under physician’s care for colds, grippe and influenza. St. Mary Academy closed; the superintendent of Schools estimated that there were 125 -150 cases of influenza amongst students at the public schools. More students were being kept at home to prevent them catching the disease.

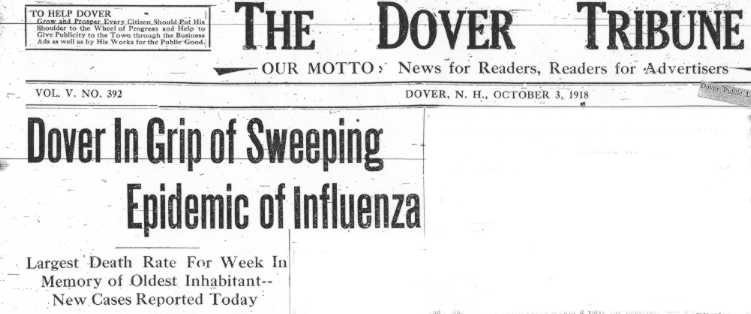

The worst days of the epidemic were October 1 and 2, when twenty people died. Physicians stated that pneumonia was developing in a large number of cases. Several doctors were "forced to refuse over a score of calls, many of them being pitiful cases".

During the height of the epidemic, physicians were under severe strain, some on the verge of breakdown. The Dover Red Cross volunteers worked at the office of the board of health answering the telephone, and assisting in obtaining help for medical emergencies. They also provided gauze masks for those attending the sick. The Sisters of Mercy also assisted with the afflicted. Foster’s Daily Democrat noted the rapid increase in intensity of the epidemic. “The physicians here are working to the limit but in spite of this there are many cases in Dover that have not yet been treated by a physician. Several deaths have occurred during the past forty-eight hours where no doctor had been secured and there are now several instances where entire families are in bed with the disease and have been unable to secure any physicians.”

There was not much doctors could do to combat the Spanish Influenza. Some recommended an old fashioned remedy for the grippe that consisted of quinine and whiskey. Four local doctors urged that wartime prohibition be repealed in order to make the remedy more easily available. Other suggested treatments were aspirin of Dover’s Powder, Oil of Hyomei , and Vick’s VapoRub. Vick’s VapoRub was relatively new to New England at this point. By mid November supplies of Vicks VapoRub had been wiped out and the company was asking pharmacists to conserve their stock.

The news reports of October 3rd were grim. “Dover is in the grip of an epidemic, the extent of which has never been known by the oldest inhabitant. The general affliction is influenza, followed by pneumonia in a vast majority of cases, nearly all of which prove fatal. Deaths have been on the increase since Monday morning, with an unprecedented death toll up to Thursday night. Many new cases of influenza and pneumonia were reported by physicians today, and during the last 24 hours, deaths have occurred almost hourly….The undertakers like the physicians are having sleepless nights caring for the dead, and early this morning no less than five bodies of dead soldiers from the training camp at Durham lay side by side at the undertaking rooms of Tasker & Chesley.” The Wentworth Hospital was full to capacity, and had to close its doors to visitors. Newspapers had pages and pages of obituaries of flu victims; William Belts, soldier; James Duke, a three year old boy; Mrs. Mary Foley, mother of five; Joseph Foley, her son; Daniel McCoole, ten years old; John McCann, thirteen years old…..

The Surgeon General of the United States warned citizens not to call upon doctors for mild cases of the flu due to an acute shortage of doctors and nurses across the country. He said the present generation was spoiled by having readily available medical care. He suggested that sick people be put to bed in a well ventilated room cleared of unnecessary furniture. He advised against using handkerchiefs to catch the patient’s considerable mucous discharge. Rags should be used and burned afterwards. The attendant should wear a gauze mask over her face, and a washable gown or apron. He also suggested that attendants might want to learn how to use a fever thermometer.

By October 10, the situation seemed to be improving. The number of deaths was decreasing as was the rate of new cases. Local doctors and health officials were encouraged by October 17 as the number of new cases continued to drop and there had been only six deaths in the last 48 hours. The health department began to consider repealing the ban on public meetings. ‘ “The situation looks brighter and better,” said Mr. Whitely of the health board to a Tribune man today, “and with a decrease of nearly 75 percent in new cases, with continued improvement in conditions, I see no good reason,” said Mr. Whitely, “why the ban on schools and public gatherings cannot be lifted by the end of the present week.”’

The Census Bureau released figures in November that estimated that the recent epidemic had been more deadly that World War I. Statistics gathered from around the country showed that from September 9 to November 9, 82,306 deaths resulted from the Spanish Influenza epidemic.

There was a brief resurgence of flu cases in early December, but the flu seemed to be milder. Health Officer Whiteley stated December 16 that there had been more than 2,000 cases of influenza in Dover during the epidemic which began “September 20, when the first death occurred and ending on November 14th., with the last death there were 80 deaths in all from influenza and pneumonia combined, 60 of the deaths being from the latter.” “Very few cases of influenza are reported in town at the present time and the health department is confident that no serious situation will develop here providing the people use care.”

Wentworth Hospital summed up the epidemic well in their report in the 1918 Annual Report of the City of Dover:

“When the epidemic of influenza reached us it found the entire force of the hospital already greatly over-worked. We prepared, as be we could, for this epidemic, but no one of us could appreciate how much would have to be done and neither did we know how virulent the disease was and how many of the nursing force would fall ill when exposed. Of the twenty-one nurses in the hospital at different times, eighteen developed influenza, fortunately not all at the same time and not all were seriously ill. There were, however, fourteen of the working force ill at one time, and the hospital was full to capacity. We had room for only the seriously ill patients and these we took in as fast as we could.

Many of the patients were at death’s door when admitted and had reached that condition without medical or nursing care. It is not my intention to dwell upon the horrors of the influenza situation, horrors shared by every hospital in the country taking in influenza patients. The difficulty of controlling delirious patients reached a point beyond the experience of any of us. Those who saw it through from the beginning have night-mare memories that time can never wholly efface.”

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.