Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

Shipping in Dover

Almost four centuries have elapsed since the Europeans first settled the land that was to become Dover. The location chosen by the first setters at Hilton Point (now Dover Point) could not have been more advantageous. The area consisted of a wooded peninsula t the convergence of several rivers and the bay. At that time, waterways provided the main, if not only route of transportation.

The first settlers were engaged in fishing, the original purpose of the settlement. Both banks of the settlement were lined with numerous slips, landings, and shipyards. Not only were there small shipyards for building small boats for citizens, but in 1661, a naval frigate was built at Dover Point for the British government. In Dover’s early history, shipping masts, dried fish, and beaver skins for Europe were the staples of the area’s economy. Lumber for barrels and casks was hewn at Dover sawmills and regularly shipped to the West Indies in trade for rum and spices. Dover Point thrived as a waterfront village for about 150 years, until the Industrial Revolution moved the center of activity to the Cocheco River.

During the 17th century, ships coming into Dover from foreign ports had little difficulty as the settlement’s commercial center was at Dover Neck where the rivers were wide and channels deep. As the town moved northward to its present site, a landing was established below the falls of the Cocheco. About 1785, the inland settlement at Cocheco (now downtown Dover) became the population and business center of Dover. Importing goods to the Landing’s piers became a more complicated operation. Most commercial shipping occurred on the Cocheco as the Back/Bellamy River was too shallow and too crooked for most sizeable vessels. Even so, the Cocheco was difficult to navigate for the larger ships except at high tide. It was during this period that the gundalows evolved. Each gundalow would carry over 30 tons of cargo and could dock at Dover Landing at half-tide.

Much of Dover’s early commercial shipping success is due in large part to the flat bottomed gundalow, a watercraft indigenous to the Piscataqua region. Named after the Venetian gondolas, it was designed to carry freight and passengers, navigating the shallow rivers and dangerous currents. At first, they were square-ended, undecked, and had no permanent or attached rudder. During the early part of the nineteenth century, a rudder and tiller were adopted and in some cases, small square sails and removable masts. Later, the spoon-bow and round stern appeared, as did a short, stubby mast rigged with a lateen sail. With a crew of two or three men, these large gundalows made good speed on the river. The operators were described as a special breed of boatsmen.

Gundalow

By 1800, over a dozen brickyards were prospering along Dover’s waterfronts, firing their kilns with 30,000 tons of cordwood delivered annually by the gundalows. Brick making in Dover began very early in the settlement at Dover Point and Dover Neck Brickyards. It became a very large and profitable business. Gundalows went down the coast to Boston and Cape Cod carrying bricks and granite, returning the next week with a load of bog hay or meadow grass. Much of Boston’s fine architecture was constructed with Dover brick.

Small packets (keel boats 30 – 40 feet in length) sailed regularly into Portsmouth, Portland, and Boston, carrying light freight and passengers. By 1825, with the formation of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company’s gigantic mills surrounding the downtown falls, Dover was the second largest town in New Hampshire, behind Portsmouth. Local shipyards built at least a half a dozen vessels each year ranging from 30 to 600 tons.

In 1835, after hearing rumors that the railroad was coming to Dover, previously in competition with each other, formed the Despatch Line of Packets, a fleet of seven vessels promising regular routes to other east coast cities. By 1840, nearly 200 ships came into the port of Dover (many having to be “lightered” by the gundalows) and the value of goods shipped just between Dover and Portsmouth was $2.4 million.

In 1877, the Dover Navigation Company began operations. Owners of the 10-schooner fleet were a group of ambitious Dover businessmen who made a profitable investment in shipping coal and finished cotton to and from ports around the world. In 1888, Dover citizens admired the “J. Frank Seavey” at the Landing: 144 ft long, 34 ft wide, and carrying 600 tons of coal for the mills. In fact, because the Cocheco River had been dredged and widened, during the last decade of the nineteenth century, it was common to see eight or nine schooners in port at one time.

However, commercial shipping traffic to downtown Dover ended abruptly on Dover’s Black Day: March 1, 1896. A late winter storm ravaged the city, destroyed bridges, and causes a ten foot rise in river levels. The storm deposited back into the Cocheco River all the sand, silt, and debris that had been dredged out over the previous sixty years. The Landing never recovered from the devastating blow.

From the 1995 Heritage Trolley Tour

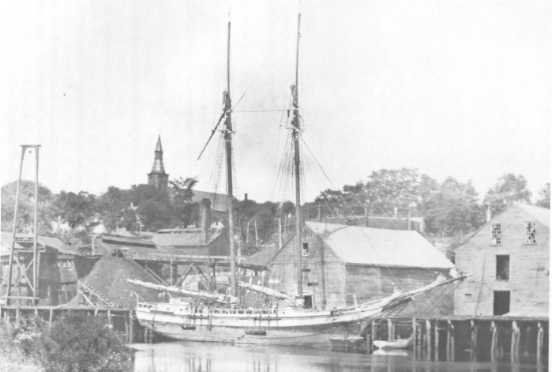

Dover Landing circa 1895

During the 18th century, development was slow along the river, but every citizen’s existence was tied to its waters. Gundalows carried raw materials and finished good back and forth to Portsmouth and the population of the “Village of Cochecho” gradually grew to the same size of that at Dover Point. Dover boatyards built small schooners and enterprising men like Michael Reade made fortunes in the lumber business. But the riverbanks here were mainly used for storage of cargo and cordwood until 1785. In that year, town selectmen voted to sell and/or lease lots bordering the Landing (around what is now the back of the old Clarostat mill.) By the end of the 18th century, Dover Landing had a bakery, a tavern, retail stores, a clock maker, a newspaper (The Sun), a distillery, a tannery, a hardware store, and a dram shop.

By 1810, ten gundalows were in constant use on the river. Each could carry over 30 tons of cargo and could come up to the landing at half-tide. Over a dozen brickyards were prospering, suing the good clay from the riverbanks here and firing there kilns with the 30,000 tons of cordwood that were delivered annually. Small packets also regularly sailed to Portsmouth, Portland, and Boston, although they could only reach Dover Landing at high tide.

By 1825, Dover was the second largest town in New Hampshire (behind Portsmouth). Dover shipyards produced as many as six vessels a year ranging in size from 30 to 600 tons. In 1835, Rogers and Peirce launched a 300-ton ship from their yard on the Landing.

However, on June 30, 1842 The Boston and Maine Railroad finally made its connection into Dover and opened a station on Third Street. Here was a means of transportation not dependent on weather or tides and boasting of modern conveniences and regular schedules of delivery. Shipping declined rapidly in the 1850s and 60s.

The Dover Gas Light Company organized in 1850 and located their gasworks at the old distillery site. In 1868 they offered to share expenses with the city in clearing out obstructions near Landing wharves. The Dover Board of Trade got involved and in 1871, the first federal funds for dredging ($10,000) were approved by Congress. During this decade, the Narrows was widened and the Gulf was deepened to 10-14 feet depending on the tide. Shipping to the port of Dover gradually increased once again and dredging funds continued to be approved.

In 1877, the Dover Navigation Company was organized by an ambitious group of local business men looking for a profitable investment. They saw the resurgence in commercial shipping by schooner and knew the industrial and mercantile needs of Dover. They decided to build a vessel capable of hauling large cargoes, particularly coal, right into the downtown wharves. The “John Bracewell,” a three-masted schooner 113 feet ling and 29 feet wide, was built in Bath, Maine for $13,000. It was launched in 1878 and the ship could carry 350 tons. It met with immediate success and more schooners, each larger than the last, quickly followed. By 1889, the Dover Navigation Company owned ten schooners, two of which were too large to ever dock in Dover! But on December 7m 1888, Dover people did get to see the “J. Frank Seavey” at the Landing. She was towed into port by a tug and the local newspaper boasted, “The Vessel is a beauty..with the largest cargo that ever came… without lightering. This shows that this is the vessel for the port of Dover.”

From the 1994 Heritage Walking Tour booklet

Schooner Thomas B. Garland

I herewith submit the reports of the business of this vessel for the years 1908 and 1909.

During our more than thirty years in the coasting business we have never found the business so poor as in the past two years, both in the difficulty of finding business for vessels and the low rates o freight paid for carrying. On this class of vessel we pay the captain 60 per cent of the gross earning after the port charges are paid. For eight years previous to 1908 the average yearly amount which the captain drew from the vessel was $3,215.79, out of which they have to pay the wages of their crew and provision the vessel. As will be seen from this report for the past year the captain has received $2,201.86 and they claim that owing to low receipts and the high price of wages of crew and provision of the vessel that they do not get fair compensation for their position as master, the upkeep of the vessel for the ten years for renewals and repairs averaged $1,158.55 per year.

It is possible that business on the coast may be better another year. I do not look for much improvement, for coasting conditions have entirely changed from what they were when these vessels were built. Our vessels are old and it cost more from year to year to keep the, up. Out of a former fleet of ten vessels we now have four left. For years the enterprise has been a waning one with this company. I am entirely satisfied in my own mind that we ought to sell the vessels for what they will bring in the market and wind the business up.

In the spring of 1908, Capt. Anton H. Benson, who had been in our employ for many years as the master of the schooner “John Bracewell,” took charge of the “Garland” and as she was very badly in need of repairs the vessels was sent to Belfast, Me., and overhauled at an expense of $1,147.92. To meet these bills $800. was hired at the Strafford National Bank, and note insured, and the balance was carried in open account by treasury of our vessels. Capt. Benson was unable to find paying business for the vessel and only seven cargoes were carried during 1908, while the vessel lay at Stonington, Me., Capt. Benson was attacked with Typhoid Pneumonia and died aboard his vessel.

The vessel the past year has been in charge of Capt. Ellery O. Garland of Portsmouth, N.H., a very competent man, The vessel closes the year $400 in debt.

This vessel was built in Bath, Maine, and launched in April, 1881, and cost $18,515.55 or $578.61 1-32 interest. She ahs paid 234 per cent or $43,320.12 in dividends or $1,353.75 per 1-32.

Respectfully submitted, B. Frank Nealley, Treasurer

Dover, N.H., January 25, 1910.

From "Dover Schooners". Undated, no author.

For more information on shipping in Dover, make sure to read "Port of Dover: Two Centuries of Shipping on the Cochecho" by Robert A. Whitehouse, c. 1988.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.