Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

Enslaved People in Dover

The first evidence of enslaved people in Dover comes from Breaking the Bonds: The Role of New Hampshire’s Courts in Freeing those Wrongly Enslaved 1640s-1740s by Robert Dishman in The Historical New Hampshire v 59 #2.

"The Torr family in Dover was involved in several “Freedom Suits” in which slaves sued their owners for unlawfully keeping them. Benedictus and Leah Torr purchased Samson “a negro slave” in 1724. The Torrs decided Samson should be freed after their deaths and signed a ‘deed of gift” to establish that. Instead, Samson was claimed by Nathaniel Randall after their deaths. In 1741 Samson ran away from his new owner, believing himself to be a free man. He was arrested and brought to court where he showed his deed of gift. The court ruled against him and he remained a slave.

Phebe and her mother, Nanny, were also slaves of the Torr family. In 1731, Benedictus and Leah Torr indentured Phebe to a neighbor for 16 years, after which, they intended to free her. After 7 or 8 years Phebe returned to the Torrs. After Leah’s death Benedictus Torr sold Phebe and Nanny to his nephew Vincent instead of freeing them as promised. Phebe spent the next 10 years with Vincent Torr. In 1744 she declared that she would no longer work for him as a slave. In 1750 she managed to get a prominent lawyer, William Parker, interested in her case. By 1751 Phebe Nong was at last free."

Other sources of early Dover history also mention the issue. The following paragraphs are excerpted from an essay on shipbuilding in History of Dover, New Hampshire. vol. 1. : Containing historical, genealogical and industrial data of its early settlers, their struggles and triumphs by John Scales, c. 1923.

"It is not on record that Dover sea captains went to Africa and got cargoes of Negroes in exchange for rum, as English captains did, and carried them to the West Indies, and sold them to the sugar planters, but it is a well known fact that they bought some of those men from the slave dealers and brought them to Dover and sold them to rich men here, who held them as slave to the ends of their lives. Some of these Negroes were living at the beginning of the Revolution, and some of the slaves served with their masters in the army that was fighting for American Freedom.

Of course only a few of the wealthier men in Dover could afford to purchase Negro Slaves, and those who did were not hard masters, but treated their servants kindly; gave them plenty to eat and , no doubt, gave them plenty of work to do. There is a record of one marriage of slaves in Dover. It can be found on page 174 of the 'Dover Historical Collections'.

'December 26,1774.—Richard, Negro servant to Mark Hunking, Esq., of Barrington, and Julia, Negro Servant to Stephen Evans, Esq., of Dover, by consent of their respective masters.' Rev. Jeremy Belknap officiated. Colonel Stephen Evans was the most distinguished military officer Dover had in the Revolution. Captain Mark Hunking was a wealthy retired sea Captain of Portsmouth, who spent the last twenty-five years of his life in Barrington. His residence was at 'Beauty Hill,' near Winkley’s Pond."

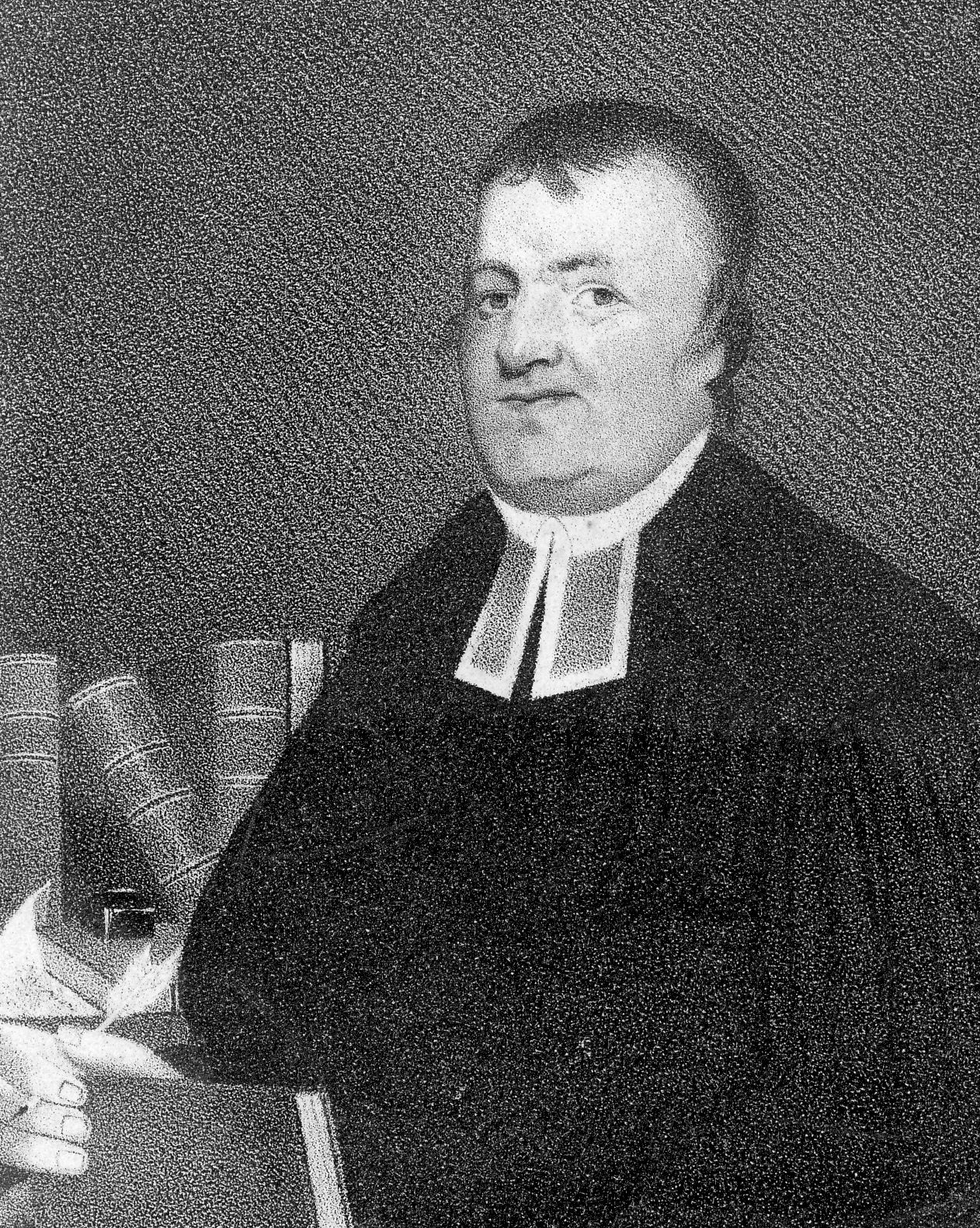

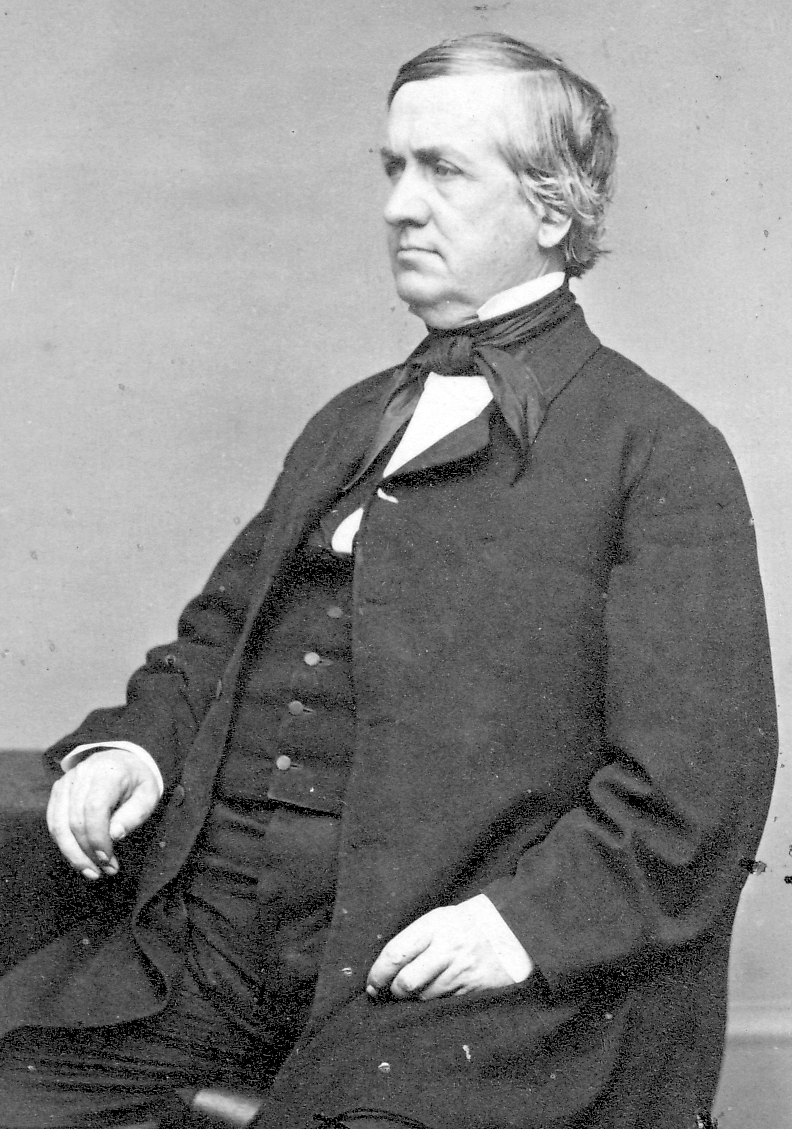

Reverend Jeremy Belknap

Reverend Jeremy Belknap

According to The History of the First Parish Church Dover, New Hampshire, ‘In 1769 the most illustrious minister of the First Parish Church took office. He was Rev. Jeremy Belknap, who served until the year 1786. Mr. Belknap became a prominent man of his time. …. At the pulpit of this very church, even at the time of the Revolution, he condemned slavery, inflations, and the union of Church and State. On Slavery he said from the pulpit in 1774. “Would it not be astonishing to hear that a people who are contending so earnestly for liberty, are not willing to allow liberty to other? Is it not astonishing to think that there are at this day, in several colonies upon this continent, some thousands of men, women and children, detained in bondage and slavery for no other crime than their skin is of a darker color than our own? Such is the inconsistency of our conduct! As we have made them slaves without their consent and without any crime, so it is just in God to permit other men to make slaves of us”.’

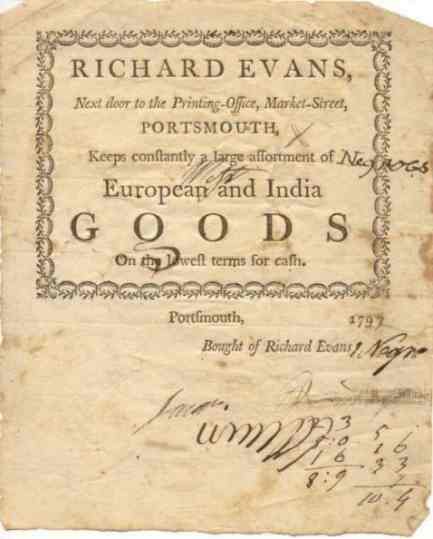

This receipt for a "negro" purchased at an auction in 1797 was found in a pile of materials that were waiting to be added the Library's historical collection.

Notable Events in the History of Dover, N. H. by George Wadleigh explains in "December 1775, 'By a census of the State taken this year 'For the purpose of establishing an adequate representation of the people,' Dover was found to contain males under 16 years if age 410, males from 16 years of age to 50 not in the army 342, males above 50 years of age 74, persons gone in the army 342, all females 786, negroes and slaves for life 26—total 1666'.

December 1777

The 'institution of slavery' existed, (though it could hardly be said to flourish) in Dover, until after the Declaration of Independence. December 6, 1773, Colonel Otis Baker bought of Henry Ward of Newport , Rhode Island, 'a negro boy named Cato,' which boy aforesaid Ward, for and in consideration of the sum of 'one thousand four hundred pounds, old tenor,' promised the said Baker to 'defend him and his assigns forever, against the lawful claims of all persons whatsoever.' June 4,1777, Colonel Baker gave Cato his freedom, the certificate of emancipation being signed by Jeremy Belknap as witness. As already stated, by census of 1775 there were '26 negroes and slaves for life' in Dover that year. These were mostly emancipated by their nominal owners during the revolution, or all became free by general consent and the adoption of the State Constitution soon after. Many of them however, remained for life in the families which they had faithfully served as slaves, preferring the protection of their old masters to the larger liberty which was offered to them."

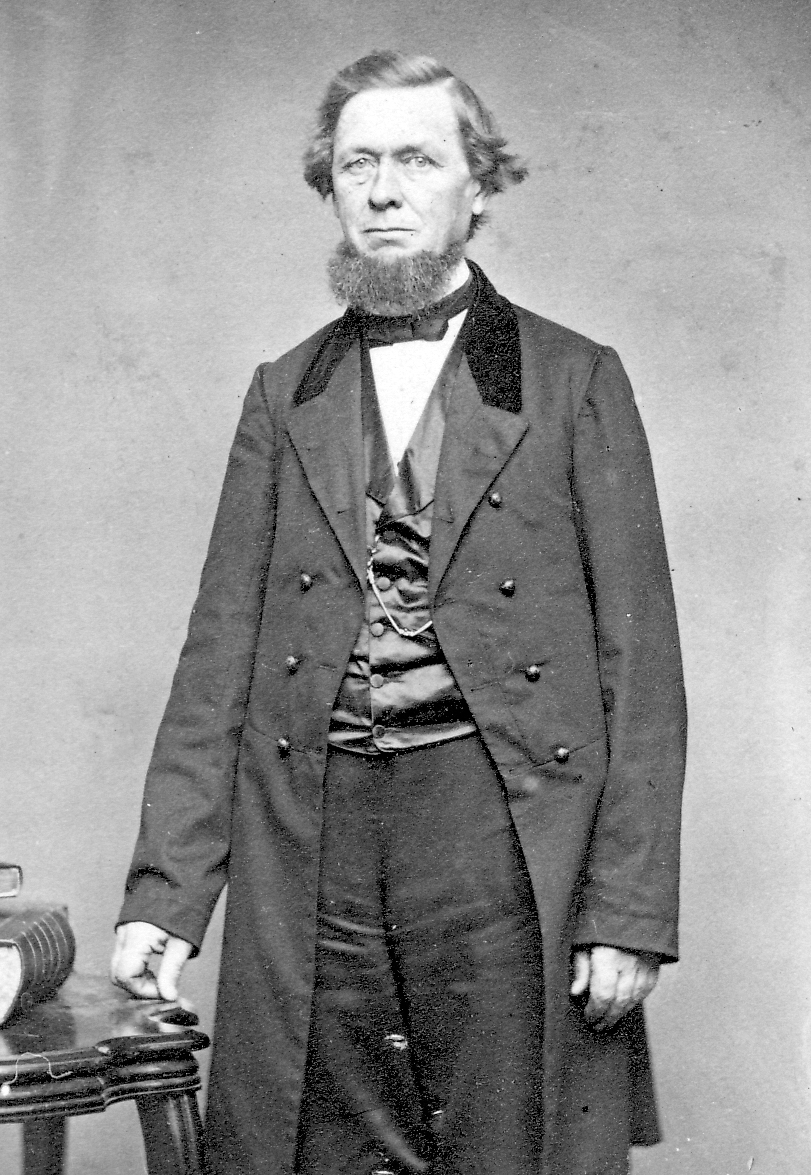

The History of the Dover Baptist Church Dover, New Hampshire 1840-1945 by William Edgar Wentworth has some interesting stories about "William Burr, who by 1835 had been made both editor and publisher of The Morning Star as well as agent for the trustees of what ultimately would become known as the Freewill Baptist Printing Establishment, began more and more in columns of the newspaper to rail against the evils of slavery…

Solid proof has not surfaced concerning any actual instances in which Washington Street Freewill Baptists helped fugitive slave along the Underground Railroad to safety in Canada, Records of such actions, for obvious reasons, seldom were kept. But it is known that some slaves traveled though the area on their way to Canada, and William Burr’s biographer, Rev. J.M. Brewster, at that time a member of the Washington Street Church and a fellow worker with Burr at The Morning Star, says: “Mr. Burr was, during those years, what might be termed a practical anti slavery man. More than once the hunted fugitive found protection within his dwelling, and was speeded by him in his flight from bondage to liberty.”

William Burr

William Burr

Brewster then recounted a story he had hear about Burr:

One morning as he was deeply engaged in business, a fugitive, who had grown gray in the service of a southern master, entered his office and gave him a letter of introduction from a Friend [Quaker] residing in Philadelphia. As the colored man passed the latter to him, he tremblingly inquired, “Are you an abolitionist?” Mr. Burr, reading the letter, at once replied, “I am abolitionist enough to take care of you.” The emphasis and almost sternness with which these words were uttered, terrified the poor fellow, who feared that he had fallen into the hands of an enemy, The kindness, however, with which he was treated and the hospitable manner in which her was received into Mr. Burr’s home, soon quieted all his fears, and he came to feel and know that he had found a friend indeed.

If the above anecdote is true, it would mean that at least this one fugitive slave traveling the Underground Railroad was harbored in the very building in which the Washington Street Freewill Baptists met for services, Burr’s office being on the ground floor. Burr’s home at the times, where his biographer says this black man and others were sheltered, was at the corner of Washington and Belknap streets, where it still stands only a block from the present church building."

A Fast Sermon on Slavery Delivered April 2, 1835 to the Congregational Church & Society in Dover, NH by David Root, pastor exhorted ‘We are all directly or indirectly implicated in this iniquitous system of oppression. Let no one suppose that the South alone are to be blamed. We are guilty. By our indifference, our connivance, and countenance, we have tolerated slavery.

The slave trade will never terminate but with the termination of slavery. The traffic in the bodies and souls of men, both foreign and domestic, will continue, until the demand for slaves ceases, and that demand will cease only with the abolition of slavery. And be it remembered, that in the eye of heaven, there is no difference between slave trading and slave holding. The abettor is criminal equally with the principal.’

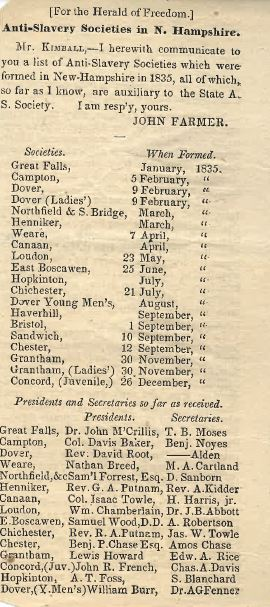

Antislavery sentiment was growing in New Hampshire. This list was published in 1835.

Notable Events in The History of Dover, N.H.by George Wadleigh wrote about the plight of Plato Waldron in "July 14, 1835.--Plato Waldron, aged about 56, (colored) drowned in the Cochecho, near the Landing. Plato was born a slave of Thomas Westbrook Waldron and was probably about the last member of the “peculiar institution” who was born, lived and died in Dover. For many years previous to his death he was Janitor of the Courts when in session in the old Court House.”

This Sermon Delivered before the Anti-Slavery Society of Haverhill, Mass Aug. 1836 by Rev. David Root reflected the abolitionist movement in Dover. ‘The essential principles of abolitionism are generally known. They hardly need be repeated. If, however, I were to sum them up in a few words, I would say that slavery is sin, a heinous violation of the word of God, and an outrageous infraction of the dictates of natural justice; because it recognizes human beings as property, degrading them to the condition of cattle, robbing them of their just earnings, annihilating the law of marriage, disrupting those endearing relations of domestic and social life which God has established, introducing a state of universal concubinage, breaking up families, neutralizing the authority of the parent over the child, forcibly separating parents and children, husband and wife, exposing them to be sold to a returnless distance from each other, and finally, excluding them from the means of moral and intellectual improvement, dooming them to perpetual ignorance.”’

In May 1841 the Dover Ladies Anti Slavery Circle published this tract, Remember Them That Are in Bonds As Bound With Them by Mrs. V.G. Ramsey.

"Never was there a time which called more loudly for woman’s gentle firmness and untiring zeal to oppose the stormy element which have wrought the destruction of so many nations; never was there a cause more important presented before you, than that which now claims your attention. You are called to ezert the influence you possess to ameliorate the condition of your suffering sisters. [sic] You are called to defend the truth, which declares, that all men were created free and equal, with inalienable rights to liberty and the pursuit of happiness. You are exhorted by all the blesses you enjoy, by that religion which has raised you from degradation, and bestowed on you the pleasures of society and education, to assist in wiping away the tears of an oppressed and suffering race. When you sit down by your own fire-side, surrounded by the comforts and luxuries of life, secure in the affection of your family circle, can you forget that more than a million females in the United States, are subjected to all the terrors, the hardships, and the pollutions if slavery? When your children smile around you in conscious innocence and peace, will you not think of that mother, who clings with frantic grief to the child they are tearing from her bosom? When you lean on your husband’s arm and feel that no hand but that of death can separate you, will you not remember her who weeps in loneliness and desolation for him whose love had long been the only blessing of her miserable existence; and from whom those who claim her soul and body have forced her to part? When you thank heaven for the light of science and the inestimable treasure of divine truth, will you not think of those who are shut up in midnight darkness? Ay, and not only think of them but remember them as bound with them."

John Parker Hale was a Dover lawyer who was first elected to congress in 1843. He served one term and was nominated again. He was stripped of the nomination after repudiating the Democratic Party stance on slavery. He eventually served 3 terms in the United States Senate. His gravestone in Pine hill Cemetery bears the following inscription, “He who lies beneath surrendered office, place, and power, rather than bow down and worship slavery”.

Finally, in February of 1850, the women of Dover, New Hampshire petitioned the federal government, asking for the abolition of slavery and slave traffic in the District of Columbia, February 14, 1850. The image is from the Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives and Records Administration.

.png)

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.