Disclaimer

The Dover Public Library website offers public access to a wide range of information, including historical materials that are products of their particular times, and may contain values, language or stereotypes that would now be deemed insensitive, inappropriate or factually inaccurate. However, these records reflect the shared attitudes and values of the community from which they were collected and thus constitute an important social record.

The materials contained in the collection do not represent the opinions of the City of Dover, or the Dover Public Library.

The Strike of the Mill Girls

Dover's Mill Girls

Advertisement from the Strafford Register August 12, 1822:

Wanted to Hire: At the Dover Cotton Factory, Upper establishment, 50 smart, capable girls between 12 and 25 years of age to work in the factory to whom constant employment and good encouragement will be given.

The work was hard and the pay was low. Girls were given $ .47 cents a day plus room and board. Two cents were deducted for medical insurance. Talking was not permitted, not that it would be heard above the rumble and clatter of the machinery. The eleven hour workday was ruled by a system of bells. From March through October, work began at 6:30 a.m. and ended at 6:30 p.m. except on Saturday when the bell tolled a little earlier. The dinner bell clanged at 12:30, lunch was finished by 1:15 p.m. Workers who were late would be locked out and subjected to a 12 1/2 cent fine. The mill policy was as follows: "Yard gates will be opened when the bell for commencing work begins to ring, and closed when it stops tolling. Ringing in bells will ring 5 minutes, pause 2, and toll 3 minutes, when all hands must be in. Mill gates will be hoisted when the last bell begins to ring."

The work was also dangerous. Newspaper accounts frequently reported accidents such as a woman's hand being mangled in machinery, or a girl losing her scalp when her hair became stuck in the looms.

Unmarried mill girls lived in boarding houses that were built and run by the management of the Cocheco Manufacturing Company. Girls could get permission to live elsewhere but it was discouraged. Widows were hired to run the boarding houses. The widow in charge assumed responsibility for the physical and moral well-being of her charges. The mill company posted strict rules of behavior for the girls to follow.

The factories changed hands in 1828. The new owner was even more strict. Wages were reduced by five cents a day for female workers, but not men, who were already paid at a higher rate. The mill girls were finally driven to rebellion, enacting the first women's strike in the United States. On December 30, 1828, about half of the 800 mill girls walked out. They marched around the Mill with signs and banners and even ignited two barrels of gunpowder.

Local newspapers were biased in favor of Dover's major industry, the mills, in their reporting of the incident. The Dover Enquirer December 30, 1828 wrote:

Turn Out- A general turn out of the girls employed in the cotton factories in this town to the number of 6 or 800 took place on Friday last, on account of some imaginary grievance. It has, we believe, turned out to their cost, as well as disgrace; and since that time many of them have returned to work, and all, who are permitted, will without doubt, return in the course of a few days.

The girls on leaving the factory yard formed a procession of nearly half a mile in length, and marched through the town, with martial music: accompanied with roar of artillery. The whole presented one of the most disgusting scenes ever witnessed.

On the weekend following the turn out, over 6oo of the mill girls met to formulate a plan. They passed the following resolutions:

1st, Resolved, That we will never consent to work for the Cocheco Manufacturing Company at their reduced "Tariff of Wages".

2nd, Resolved, That we believe the "unusual pressure of the time", which is so much complained of, to have been caused by artful and designing men to subserve party purposes, or more wickedly still, to promote their own private ends.

3rd, Resolved, That we view with feelings of indignation the attempt made to throw upon us, who are least able to bear it, the effect of this "pressure" by reducing our wages, while those of our overseers and Agent are continued to them at their former high rate. That we think of our wage already low enough, when the peculiar circumstances of our situation are considered; that we are many of us far from our homes, parents, and friends, and it is only by strict economy and untiring industry that any of us have been able to lay up anything...

We view this attempt to reduce our wages as part of a general plan of the proprietors of the different manufacturing establishments to reduce the females in their employ to that state of dependence on them in which they openly, as they do now secretly, abuse and insult them by calling them their "slaves".

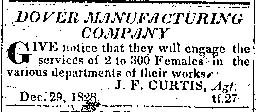

In spite of these resolutions the Dover mill girls were forced to give in when the mill owners immediately began advertising for replacement workers. Striking workers returned to work January 1, 1829 at reduced wages.

This historical essay is provided free to all readers as an educational service. It may not be reproduced on any website, list, bulletin board, or in print without the permission of the Dover Public Library. Links to the Dover Public Library homepage or a specific article's URL are permissible.