- About Dover

- Business in Dover

- City Government

- City Services

- Budget Revealed »

- Building Inspection Services Permits and Forms »

- Current Bids »

- DNTV On Demand »

- Election Information »

- Employment »

- Motor Vehicle Registration »

- Parking Violation Payments »

- Online Permits »

- Planning »

- Pay My Bill »

- Public Library »

- Public Welfare »

- Public Safety »

- Recreation »

- Recycling Center »

- Tax Assessment »

- Vital Records »

- Water/Sewer Billing »

- Contact Us

Indigenous Dover

In 2021, the City Council passed a resolution that acknowledges the people who tended to what is now called Dover, long before it was called Dover. The land acknowledgment reads:

"This (event/meeting) takes place at Cocheco (CO-chi-co) within N’dakinna (n-DA-ki-na), now called Dover, New Hampshire, which is the unceded traditional ancestral homeland of the Abenaki (a-BEN-a-ki), Pennacook and Wabanaki Peoples, past and present. We acknowledge and honor with gratitude the land, waterways, living beings, and the Aln8bak (Al-nuh-bak), the people who have stewarded N’dakinna (n-DA-ki-na) for many millennia."

Bronze plaques containing the land acknowledgement were installed at city facilities and public schools.

This page, made possible with the support of the New Hampshire Humanities Council, will continue to be updated with resources that aim to shed more light and foster a deeper understanding of Dover's indigenous history.

This page, made possible with the support of the New Hampshire Humanities Council, will continue to be updated with resources that aim to shed more light and foster a deeper understanding of Dover's indigenous history.

New Hampshire's first settlers

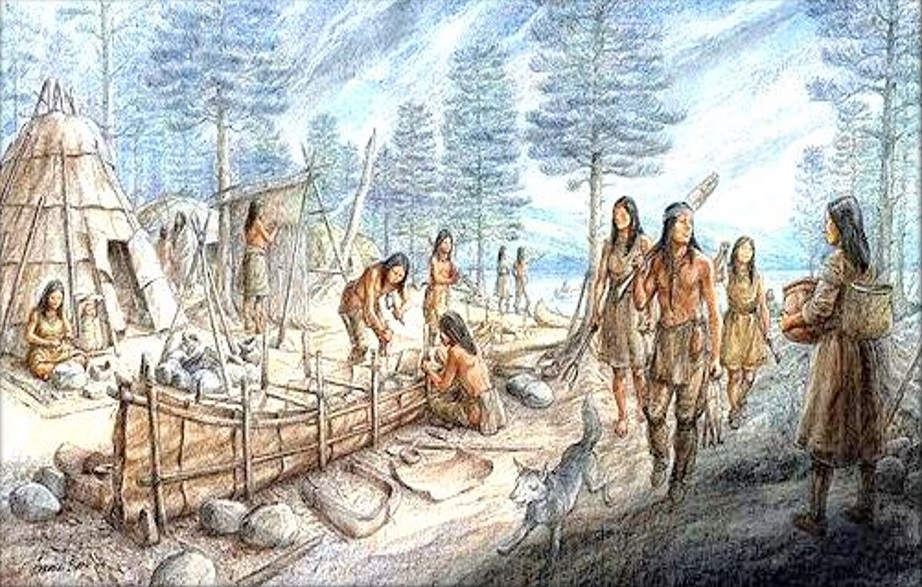

We will never know the names or the languages of the first people who came to what is now New Hampshire.

They arrived about 12,000 years ago and the passage of time and movements of people have obscured their origins. The descendants of these people divided into bands-often called tribes. Among them were the Penacook, Winnipesaukee, Pigwacket, Sokoki, Cowasuck and Ossipee. All spoke related dialects of the Abenaki language.

Today these people are known collectively as the Abenaki, which is often translated as "People of the Dawnland." (woban means day-break and ski means earth or land).

Abenaki life was observed and recorded by European explorers of the early 1500s. Land was not owned, but used according to custom, season, and need. Abenaki set up villages along rivers and lakes where they had access to water and could hunt, farm and fish using traps called weirs. Favorite fishing spots were near waterfalls along the Merrimack, Connecticut, Saco, and Androscoggin Rivers. Places like Amoskeag Falls in Manchester and the Weirs at the mouth of Lake Winnepausakee drew thousands of people for the yearly spawning of shad, salmon and alewife.

By the late 1600s the Native American population in New Hampshire was declining. They had no natural immunities against diseases such as small pox and influenza that were introduced by European settlers and major epidemics broke out between 1615-1620 that decimated populations. Conflicts with invading Mohawks and tensions with European settlers claiming ownership of Abenaki ancestral lands made the situation even worse. By the end of the century many of the remaining Abenaki had either married Europeans, melted into the rural population, or decided to leave and settle in Canada. Many settled in the village of St. Francis in Quebec, also known as Odanak.

The native Americans of the northeast all spoke related dialects of a language known as Algonquian. Today there are less than a 1,000 Abenaki in New Hampshire and only a few who speak the language. In 1995 Joseph Laurent, an Abenaki born in Odanak and then moved to ancestral lands in Intervale NH, completed a 30-year project to translate "Father Aubery's French Abenaki Dictionary." This important work will help ensure an understanding of the beauty of the language.

Source: https://www.nh.gov/folklife/learning-center/traditions/native-american.htm

Additional online resources

Below are links to additional online resources that provide more information about indigenous peoples in the Dover area:

- Abenaki Nation of New Hampshire

- Abenaki Language Revitalization

- The Pennacook Tribe of New England

- The Cowasuck Band of the Pennacook Abenaki People

- Indigenous New Hampshire Collaborative Collective

- Native American Heritage

- From the Fragments: The Places and Faces of Great Bay Archaeological Survey

- Indigenous People of Piscataqua Watershed: A Dover400 Lecture

- Dover in the 17th Century: Abenaki Life and History from an Indigenous Perspective: A Dover 400 Lecture

- Dover 400 Year Anniversary

- People of the Dawnland exhibit at Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth,NH

- Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum

- New Hampshire Intertribal Native American Council

A wide variety of historical information about Dover's indigenous peoples are available at the Public Library and from other sources. Below is a list of recommended reading for more information.

The following books are available at the Dover Public Library:

- Belknap, Jeremy, Belknap's History of New Hampshire: an Account of the State in 1792. Hampton, N.H., P. E. Randall,1973.

- Brooks, Lisa Tanya, The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

- Brooks, Lisa Tanya, Our Beloved Kin : a New History of King Philip's War. New Haven : Yale University Press, 2018. https://www.ourbelovedkin.com/awikhigan/index (enter Waldron into the search engine) The Captivity at Cocheco William Waldron's Defense:The Capture and Return of Wabanaki Noncombatants

- Bruchac, Jesse Bowman, Abenaki Dictionary. Greenfield Center, NY: Bowman Books, 2019.

- Bruchac, Joseph, The Heart of a Chief. New York: Dial Books for Young Readers, 1998.

- Bruchac, Joseph, The Winter People. New York, NY: Dial Books, 2002.

- Calloway, Colin G., Dawnland Encounters : Indians and Europeans in Northern New England. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1991.

- Colby, Solon B., Colby's Indian History: Antiquities of the New Hampshire Indians and Their Neighbors. Exeter, N.H. : Colby, 1975.

- Goody, Robert, A Deep Presence: 13,000 years of Native American history. Portsmouth, NH : Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2021.

- Hardesty, Jared Ross, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. Amherst, MA, 2019.

- Heald, Bruce, A History of the New Hampshire Abenaki. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014.

- Masta, Henry Lorne, Abenaki Indian Legends, Grammar and Place Names. Toronto, 2008.

- Norton, Mary Beth, In the Devil's Snare: the Salem witchcraft crisis of 1692. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

- Parker, Trudy Ann, Aunt Sarah: Woman of the Dawnland. Lancaster, NH: Dawnland Publications, 1994.

- Piotrowski, Thaddeus, Indian Heritage of New Hampshire and Northern New England. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, c2002.

- Scales, John, Historical Memoranda Concerning Persons & Places in Old Dover, N.H. Dover, N.H.: 1900.

- Scales, John, History of Dover, New Hampshire. Containing historical genealogical and industrial data of its early settlers, their struggles and triumphs. Manchester, N.H.: Clarke, 1923.

- Senier, Siobhan, Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.

- Warren, Wendy, New England bound : slavery and colonization in early America. New York : Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016.

- Wiseman, Frederick Matthew, The Voice of the Dawn : an Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2001.

- Potter, Chandler Eastman,The History of Manchester, formerly Derryfield, in New Hampshire; including that of ancient Amoskeag, or the middle Merrimack valley; together with the address, poem, and other proceedings, of the centennial celebration, of the incorporation of Derryfield; at Manchester, October 22, 1851.

- Sanborn, Benning W., "Indian History" from The History of Concord, From Its First Grant in 1725 to the Organization of the City Government In 1853, With a History of the Ancient Penacooks by Nathaniel Bouton, 1856.

- Lyford, James O. "Aboriginal Occupation" from History of Concord, New Hampshire from the Original Grant in Seventeen Hundred and Twenty-Five to the Opening of the Twentieth Century Prepared Under the Supervision of the City History Commission, James O. Lyford, Editor, 1903.

The following books are available from other sources:

- Bourque, Bruce, Uncommon Threads: Wabanaki textiles, clothing, and costume. Augusta, ME: Maine State Museum, 2009.

- Dubin, Lois Sherr, The History of Beads: From 30,000 B.C. to the Present. NY: H.N. Abrams, 1987.

- Hardy, Kerry, Notes on a lost Flute: A field Guide to the Wabanaki. Camden, Me: Down East, 2009.

- Moerman, Daniel, Native American Ethnobotany. Portland OR: Timber Press, 1998.

- Orchard, William C., Beads & Beadwork of the American Indian: a study based on specimens in the Museum of the American Indian. NY: Museum of the American Indian,1975.

- Shea, John Gilmary, History of the Catholic missions among the Indian tribes of the United States, 1529-1854. New York: E. Dunigan and Brother, 1857.

- Speck, Frank G., Penobscot Man: the life history of a forest tribe in Maine. Orono, Me: University of Maine Press, 1997.

Special Presentations

As part of a series of presentations at the Dover Public Library, Paul and Denise Pouliot of the Cowasuck Band of the Penacook-Abenaki People provided a short history of indigenous foodways, and the traditional use of waterways and land along the Cochecho. The presentation also addressed contemporary efforts by indigenous groups to care for their ancestral homelands.

Dover400 began a yearlong lecture series in 2021 with two presentations on the history of Dover and the region's indigenous peoples. The presentations can be viewed below.

Want to know more? Subscribe to the City's weekly newsletter, Dover Download. Click Here. Our Web Policy | Site Map | Contact the webmaster